1956-57. Peter May’s England was in South Africa. A series full of drama, suspense, swings of fortune, and often superb cricket. The final result was 2-2, the vaunted England side being held to a stalemate by a magnificent South African attack, primarily the champion off-spinner Hugh Tayfield.

It was during this series that Trevor Bailey completed the rare feat of 2000 Test runs and 100 Test wickets. In his entertaining tour book Pitch and Toss South African batsman, Roy McLean observed that the Essex all-rounder had now joined the ranks of Keith Miller and Wilfred Rhodes.

“Just imagine the difference in spectator value between Keith Miller and Trevor Bailey either as bowler or batsman,” he wrote. McLean, of course, had never seen Rhodes but he added, “Yorkshire’s Wilfred Rhodes, who started as No. 11 batsman for England and ended by opening, was much before my time, but I’m quite sure he could, despite the county of his birth, never have been as dour as Bailey.”

The strange bit was that at that particular point in time, India’s Vinoo Mankad had 2,084 runs and 158 wickets in Tests. But he was not white enough to feature in McLean’s world of cricket as viewed from apartheid, South Africa.

In that country it was impossible to maintain a veneer of normality.

The rest of the old cricket world accepted the ‘others’ but within firmly etched limits. In many ways, it followed the slow, stumbling process of decolonisation and dismantling of the erstwhile Empire.

During the overly patronising cricketing days of the 1940s and 1950s the game was frequently categorised into Anglo-Australian encounters, county championships and other cricket … in that specific order. Even the advent of the West Indies as a major cricket power did not change the perceptions till the late 1950s and the early 1960s.

In a lot of ways Mankad did magnificently in both England and Australia, hence a McLeanesque ignorance of his performances was often difficult to adapt.

But even then, being a great cricketer from a weaker, inferior, and —let’s face it, non-white—cricketing nation, he was perhaps not as celebrated as he should have been.

He was indeed an all-rounder in the same league as Rhodes, Miller, and Bailey. But seldom spoken in the same breath.

The great days

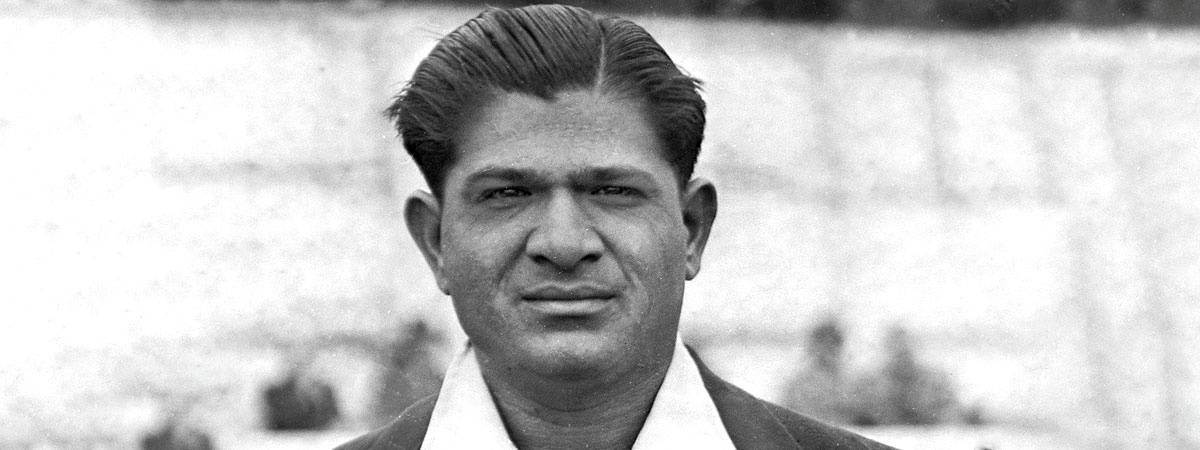

Mankad was special. The first great all-rounder of India. He could hold his own with the bat, good enough to open in as many as 40 of his 72 Test innings. At the same time he was one of the foremost spinners of the world.

That too after World War II had scooped out a major chunk of his cricketing life.

At 20, he made waves against Lord Tennyson’s team that visited India in 1937-38. In the victorious fifth unofficial ‘Test’, Mankad scored an unbeaten 113 from number three and picked up three for 18 and three for 55. He finished the series averaging 62.66 with the bat and 14.33 with the ball, leading Tennyson to remark that he would find a place in any World XI.

And then there was the Second World War. He had to wait till the 1946 tour of England to make his debut. By then he was 29.

His versatility was extensively used by the inexperienced Indian side. In his first Test, he was sent in to open with Vijay Merchant. He did not do too badly, scoring 63 in the second innings.

With Mushtaq Ali returning to the side for the remaining Tests, Mankad was pushed down the order and did not do too much with the bat thereafter. But he did pick up five wickets in England’s first innings at Manchester.

This was followed by the epochal tour of Australia in 1947-48. Don Bradman’s side steamrolled over the Indians, but Mankad opened the batting against Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller and hit two hundreds. Don Bradman was effusive in his praise. “Mankad did surprisingly well with the bat if one takes into account the enormous amount of work he was called upon to do with the ball.”

And although he did not take too many wickets, he ensured that he would live on in the annals of cricket as a mode of dismissal.

In a tour match, and thereafter in the second Test, he ran out Bill Brown as the latter backed up too far before the ball was bowled. The Australian media was infuriated enough to term this ‘questionable’ act Mankading, a term with derogatory implications used till this day. However, men like Bill O’Reilly stood solidly behind his action, and Bradman himself came out defending Mankad solidly in his autobiography Farewell to Cricket.

The winter of 1951-52 and the subsequent summer saw some of his greatest performances.

At Madras, on a wicket that was not exactly helpful, Mankad cast a spell over the English batsmen, captured eight for 52 and four for 53 as India registered their first-ever Test victory.

And then came the summer of 1952.

In the first morning of the second Test at Lord’s, Mankad walked out to open the innings and launched Roly Jenkins for a straight driven six over the sightscreen.

“I know of no precedent of such a solecism during the first hour of a Test match,” wrote Neville Cardus.

England won the Test with resources and time to spare. Yet, the match has gone down in history as ‘Mankad’s Test’.

The all-rounder top-scored with 72 in India’s first innings total of 235. England piled up 537 in response. Mankad sent down 73 overs, capturing five wickets for 196. When India proceeded on their uphill task, batting with their backs to the wall in the second innings, Mankad opened the innings again, after 31 overs of bowling that day. He went on to bat for four-and-a-half hours.

When he was bowled by Jim Laker for 184, twenty minutes after lunch on the fourth day, he had been on the field for all but three-and-a-half hours since the beginning of the Test.

Mankad went up on the honour board at Lord’s for both batting and bowling — Keith Miller was the only other visiting player to have achieved the feat till then. Since then Ian Botham emulated Mankad, later scoring a hundred and taking five wickets in the same Lord’s Test match.

According to Cardus again, “Mankad’s Oriental magic had not been exorcised in spite of settling in Haslingden to play Lancashire League.” Indeed, he had been rushed into the second Test as reinforcement, after India’s infamous capitulation at Headingley. Mankad had been away, fulfilling his contractual commitments with Haslingden.

When Pakistan visited the following winter, Mankad carried on his saga of success, capturing 8 for 52 and 5 for 79 at Delhi as India won their second Test.

It was during the series against New Zealand in 1955-56 that the by now ageing Mankad set some long-standing batting records.

In the second Test at Brabourne Stadium, he scored 223 and picked up three second-innings wickets. This was followed by the famed 413-run opening partnership with Pankaj Roy at Chennai, a world record that would stand for 52 years. Mankad scored 231 and followed it up with four wickets in another innings win. The Mankad knock would stand as the Indian Test record for 28 years.

He did prolong his career, his performances dwindling after this phenomenal peak. By 1958-59, at the age of 41, he was batting low down at No 8 and failing to trouble a truckload of phenomenal West Indian batsmen with his bowling.

However, the end results look sparkling in spite of this. In 44 Tests, Mankad scored 2109 runs at 31.47 with five hundreds, and took 162 wickets at 32.32. The figures are indeed great and might have been slightly more impressive if he had retired three years earlier.

The style and the man

Possessing great powers of concentration and solid defence, when required Mankad could hit the ball hard. Frequently essaying elegant cover drives and strong leg-side strokes, he was also perhaps the first Indian batsman to loft balls into vacant areas in the outfield without trying to clear the ground.

Along with Syd Gregory and Wilfred Rhodes, Mankad remains the only batsman to have batted at all positions in Test cricket.

As a left-arm spinner, he was one of the best in business. In his early days he toyed with a chinaman, but wisely gave it up to focus on the conventional spin. He sometimes punctuated his orthodox slow break with a faster one that deceived the best of batsmen. He could vary his flight and turn as the legend goes in infinitesimal degrees till a batsman playing forward for overs at a stretch suddenly found himself beaten, marginally out of his ground, and stumped.

With the great leggie Subhas Gupte and off-spinner Ghulam Ahmed, formed the first major spin triumvirate of India.

Finally, at the end of the day full of heroics with the bat and the ball, his dapper form would never have a hair out of place.

Mankad played in Indian domestic cricket till he was in his mid-40s. In many ways, he was a trendsetting professional cricketer in the country, offering his services to Gujarat, Bengal, Saurashtra, Bombay, and Rajasthan as he made his living from the game in independent India.

Vinoo Mankad passed away at the age of just 61.

Legend has it that when he was lying sick, nearing the end of his time in life, Subhas Gupte came to visit his old comrade-in-arms. Mankad was too ill to respond.

Could he recognise his comrade in arms? Gupte wondered.

“Do you know who I am?” he asked gently.

Mankad could not speak. In response, he raised his right hand. The non-existent ball was clutched in the grip of a leg-spinner. Gupte smiled.

In life and death, Mankad remained a cricketer. The first great all-rounder of India.