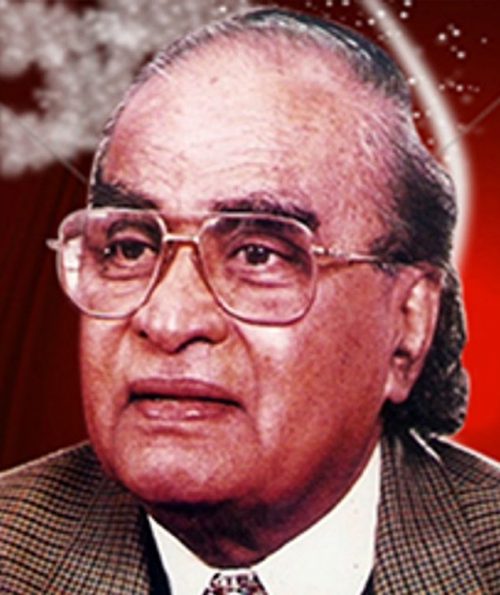

24 June 1983. In London, the Indian Minister of State for Steel and Mines, Mr NKP Salve, met Rt Hon’ble Mr Cecil Parkinson, Minister of Industries of Her Majesty’s Government, UK.

“Your Excellency, I am also a Chartered Accountant by profession,’ greeted the well-informed Parkinson. ‘…now turned a politician like you. But, what is common between steel and cricket?”

It was a delightful way of welcoming a high-profile guest. As part of his portfolio Parkinson looked after the Steel Industry in Britain, and there was obviously lots of ground for talking shop. However, Salve was not there as a Minister of State for Steel. He was in England as the President of BCCI and the following day India were supposed to take on West Indies in the title round – a round no one had expected them to come anywhere close to.

After it was mutually decided by the two ministers that, just as in world of steel, India needed ‘a little luck and pluck’ to emerge World Champions on the morrow, Salve left the offices of Parkinson and made for Brompton Square, where he was staying in the beautifully decorated flat of his brother-in-law CP Srivastava. Married to Salve’s sister, Nirmala, Srivastava was the Secretary-General of the International Maritime Consultants Organisation of the United Nations. And he was a cricket fan.

On reaching the flat, Salve was informed that Siddhartha Shankar Ray had telephoned for him. The veteran politician had been the Chief Minister of West Bengal during the Emergency years and in a couple of years would assume the role of the Governor of Punjab. During his student days he had captained the Presidency College cricket team. His wife, the lawyer and MP Mrs Maya Ray, had been a colleague of Salve in the Lok Sabha during the troubled years of 1975-77 and also a close friend. The Rays were in London and Salve called them back.

SS Ray said that he wanted to witness the finals along with his wife. Could Salve get him the necessary passes? The BCCI President was anyway thinking of getting passes for his hosts – sister Nirmala and her husband. He got in touch with Anant Wageesh Kanmadikar, the Secretary of BCCI, asking him to obtain four passes from MCC or four tickets against payment. “I must take these four persons with me to see the finals either for love or for money.”

Salve had no doubt that the request would be granted, even if it did cost the price of the tickets. “In India such courtesy to a visiting dignitary is simply taken for granted.”

However, although Kanmadikar left no stones unturned at the MCC, he returned empty-handed.

In Salve’s words: “The way Shri Kanmadikar described the arrogance of the officials at Lord’s in refusing the passes or the tickets, brought home to me the bitter reality that India may reach the top position in cricket, but in [the game’s] politics we had permanently been damned to a second-grade status. In the rule of ICC, England and Australia have been given certain authority and power in the nature of veto power.”

A few days after the World Cup final, Salve was scheduled to attend the meeting of the ICC as President of BCCI. He was “more hurt than surprised that in the world of cricket affairs India was hardly held (by the officials and members representing England) in any esteem and veneration due to an equal in community comprising the International Cricket Administrators represented by heads of various Boards enjoying Test status. It was obvious to me that the countries who were not the founder members of the ICC were not considered equals.”

Two passes had been granted earlier for the BCCI President and his wife, although the latter was not in England. Salve rang up SS Ray and offered his invitation card for the couple. Ray graciously declined.

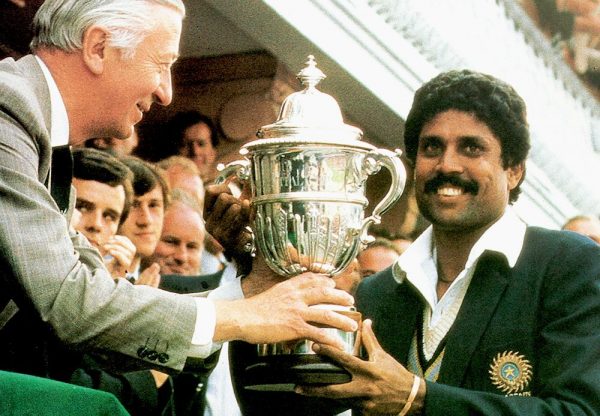

Well, Salve did witness Kapil Dev’s men script history the following day. He was in the player’s pavilion and a jubilant Kapil Dev put a bottle of champagne into his mouth and emptied the contents inside the Board President. A delighted and inebriated BCCI supremo announced unprecedented amounts as reward for the World Champions.

However, even as the team soaked in the euphoria of triumph, Salve had his sights set on the next World Cup. He had not forgotten the slight of refusal of the four tickets. The very World Cup tournament would have to be whisked away from dear Ole Blighty where the residual twilight of the Empire lingered while the sun had finally set a few years ago.

Salve wanted to host the next World Cup in the subcontinent. The first close friend to whom he spoke of this grand plan reacted, “Have you gone bonkers?”

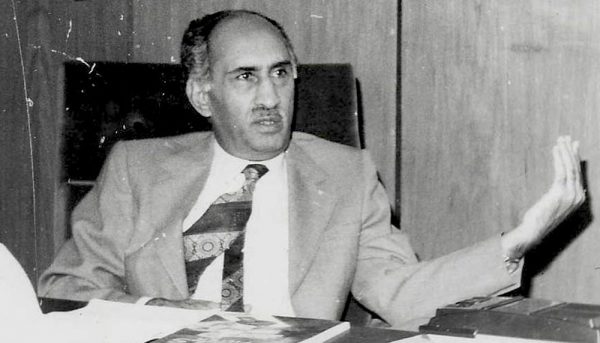

Yet, Salve started preparing the ground from the very next day. CP and Nirmala Srivastava hosted a celebratory lunch on Sunday, 26 June, the day following the final. The guests included the Air Marshal Nur Khan, chairman of the Pakistan Cricket Board, and Gamini Dessanayake, President of the Sri Lankan Cricket Board. There were several other dignitaries, including Dr Nagendra Singh, judge in the International Court of Justice, Mr and Mrs MA Chidambaram, Raj Singh Dungarpur and Lata Mangeshkar.

Salve knew Air Marshal Nur Khan well. The Chairman of the Pakistan Cricket Board had visited him in his office while Salve had been in the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. He had issued an invitation to visit Pakistan during the 1982-83 Indian tour. Salve had been received with lavish hospitality in the neighbouring nation, even entertained to dinner by Malika-e-Tarannum Noor Jehan.

Salve and Nur Khan had agreed that there were very few matches between India and Pakistan. Plans had been put in place. If we leaf through the scorebooks, we find the cricketing face-offs between the two countries became very very frequent during the early to mid-1980s. They had been in Sharjah together, invited by Sheikh Abdul Rehman Bukhatir, striking deals with CBFS and kickstarting a sizzling rivalry between the two cricketing neighbours in the desert.

Now in London, Nur Khan and Salve chatted about the final of the previous day while Dessanayake spoke to Lata Mangeshkar about a proposed musical programme in Sri Lanka. When the discussion with the nightingale ended, Dassanayeke made his way towards the two men and heard them reminiscing about the final. “What a spectacle it was to see India emerge victorious at Lord’s,” he said.

Salve responded, “I wish we had played this match in India. How wonderful it would be if some day we could play the World Cup in India.”

And Air Marshal Nur Khan turned towards him, “Why can we not play the next World Cup in our countries?”

That was the germination of the idea.

Foreign exchange was guaranteed through fortuitous meetings with the Hinduja brothers, both elated at the Indian triumph. The Asian Cricket Council was established for closer camaraderie. The associate nations Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia were roped in. Bukhatir was asked to apply for Associate membership for UAE on behalf of the Sharjah Cricket Association. The West Indians were wooed with a highly lucrative tour in 1983-84 through which Allan Rae, the President of the West Indies Cricket Board, was snared.

But doubts remained in the minds of one and all. “Can the Hindujas take care of the Rules if England and Australia together just veto the resolution?” asked former BCCI President Purushottam Rungta.

However, Salve was going through every detail of ICC rules and regulation like a man possessed. A proposal was prepared by the Treasurer of the Indian Board, Jagmohan Dalmiya.

There was a major hiccup when Air Marshal Nur Khan and his Secretary resigned from the Pakistan Board. But the men who took their places, Lt Gen Safdar Butt as the President, and Col Rafi Nasim as the Secretary, were very much in favour of the collaboration.

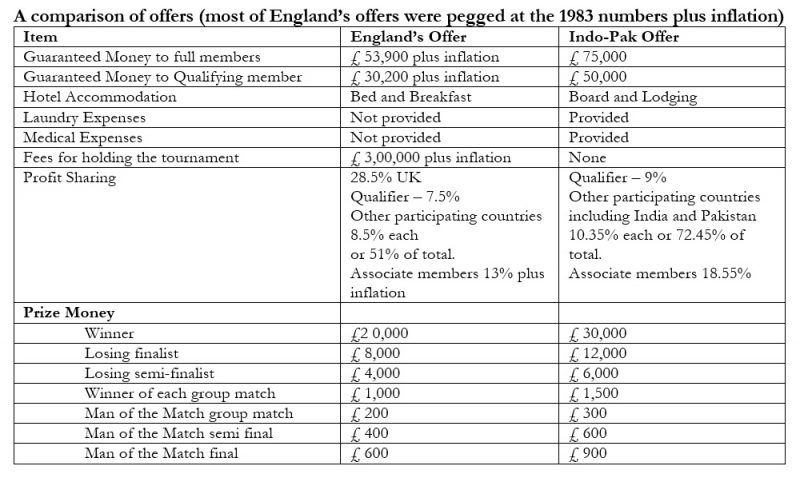

A table was prepared to show how much more financially attractive the terms of the Indo-Pak proposal were when compared to the terms offered by England. (part of the table has been reproduced at the end of this article)

On 19 July 1984, at Lord’s, this proposal was debated in a formal General Meeting of the ICC with Full Members and Associate Members. All the legalities had been considered and the differences in financial remuneration for each participant were too much to be brushed aside. The legalities ensured that the resolution could not be vetoed. Charles Palmer, President of TCCB, did have to admit, “England has never claimed that the World Cup is the divine right of England for all times to come.”

However, plenty of questions were raised about the paying capability, hotel accommodation and possibilities of bank guarantees! When the last point was raised by the New Zealand President, Salve threatened to walk out of the meeting. “I have the balance sheet of the Indian Board with me. If you must look for a guarantee, look at the balance sheet.”

The vote was carried out, and the Indo-Pak proposal pipped England 16-12.

It all started with the sanctimonious boorishness faced by Salve on 24 June 1983, the eve of the World Cup final.

(Most of the details given in the article including the final table have been obtained from NKP Salve’s book Story of the Reliance Cup)

Arunabha Sengupta is a cricket writer whose latest book – Elephant in the Stadium – was named the best cricket book of 2022 by Times, London, and was shortlisted for the “Derek Hodgson Cricket Writers” Club Book of the Year Award and for Heartaches’ Cricket Book of the Year in the British Sports Book Awards. He is also the author of Apartheid: A Point to Cover and co-author of the books Sachin and Azhar at Cape Town and The Ashes: This Thing Can Be Done.