The record-breaking feats of Younis Khan, who became the country’s highest Test run-getter, whilst batting against England, in UAE, has brought him, deservedly, in comparison with Pakistan’s three greatest batsmen – Hanif Mohammed (1951-69), Javed Miandad (1975-96) and Inzamam-ul-Haq (1991-2007). Amongst this elite group, the great Hanif Mohammed, soon to celebrate his 81st birthday in Karachi, represented the first master class of batsmanship of his country. Despite a number of health setbacks in recent years, including cancer of the liver in 2013 and a minor stroke in 2014, he refuses to go down without a fight.

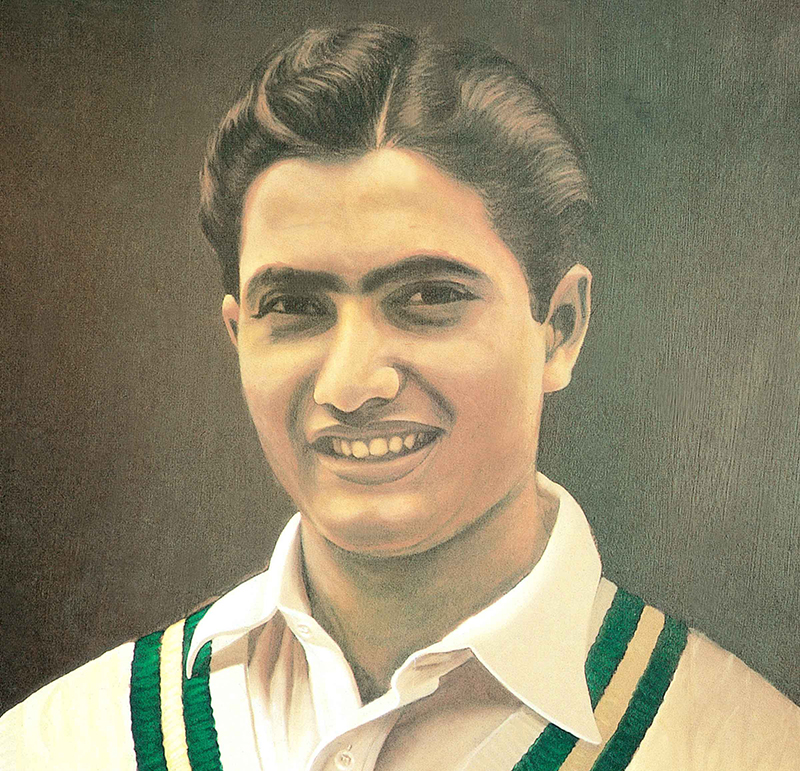

The presence of Hanif Mohammed at the batting crease remained a sight of great assurance and relief for his teammates and cricket lovers in Pakistan, for almost two decades.

Invariably, it was Hanif’s rock-solid defense upon which, Pakistan’s almost every formidable total was built. His deeds with the bat are legendary: he was simply his country’s first champion batsman, and to this day is regarded as the most consistent opening batsman in the short history of Pakistan’s cricket. The best known of the famous Mohammed brothers, Hanif held most of his country’s batting records than any other Pakistani batsman, before his controversial exit in 1969. In his distinguished career, he also had the honor of leading his country in 11 Test matches.

The story of the Mohammed family is virtually the story of Pakistan cricket. The impact of one of cricket’s most famous families, ran into the second generation, in the form of Hanif’s son Shoaib Mohammed. In the 27-year period (1951-78), amazingly, at least one of the Mohammed brothers was present in the Pakistan line-up in the Test matches. Hanif was born in Manavadar, an Indian township of Junagadh on the fourteenth day of holy month Ramadan, or in other words on December 21, 1934. He was the middle of five sons (discounting one brother and a sister who both died in their teenage) born to a professional class parent, who both excelled at ball games at an amateur level.

Their father Sheikh Ismail Mohammed, a hotel-keeper in Junagadh died prematurely in 1948, after the family’s migration to Karachi. A great admirer of Australian captain, Lindsay Hassett, Ismail himself was a good club cricketer. Their mother, Ameer Bee, who passed away in 1995 at the age of 85, was a great influence on the sports-mad clan. She was a badminton champion in India and also dominated the regional table-tennis and carrom scene.Ameer Bee made sure her boys had every possible opportunity to develop their sporting talents. That resulted in her five sons, Wazir, Raees, Hanif, Mushtaq and Sadiq, all playing first-class cricket. Apart from Raees Mohammed, who acted as 12th Man against India at Dhaka in 1954-55, the other four went on to win Test caps.

Even before the family left Junagadh for Karachi, young Hanif was busy learning his trade on the concrete terrace by the electric lights, in front of his parents’ house. He would team up with his brothers to participate in tennis ball “Test Matches that would stretch to almost a week in search of a decision. Their father would shave the mat off on one side of tennis balls to produce a delivery which could swing and provided bowlers with a better opportunity to compete on equal terms. It was during these encounters that the brothers learned to keep their

heads down and their elbows up, as a lost ball could mean a long search in the darkness.

Slogging was simply not on, under the circumstances, and this is where the family trademark, of doggedness, was born. Hanif received a good deal of coaching from Abdul Aziz, himself a wicket-keeper who represented All-India against Jack Ryder’s Australian team in the unofficial ‘Test’ at Calcutta in 1936. The first area that needed attention was Hanif’s tendency to play back too much and he could not help spooning the ball while playing defensively on the on-side. Abdul Aziz helped him to get rid of the rough edges and Hanif learned how to defend his wicket, by playing forward as well as the back. The hook and the pull were never his best strokes and because of his frailness, his drives also lacked punch. On Master Aziz’s death in 1978, his most famous pupil wrote, “He was the school cricket coach at Sind Madrassa, and now when I look back I realize what amount of hard work he put into my game.”Throughout his career, Hanif had an almost non-existent back lift of the bat and essentially remained a back-foot player. It was at this stage of his career that he developed a peculiar habit of touching his cap and before his crouch would go through the motion of making a cross over his chest before stooping to face the bowler. It was his own way of concentrating.

In Karachi, Hanif started to outshine his brothers and dominate school cricket. Wearing a red cap with a camel crest, the school emblem, he scored a record-breaking inning of 305 in seven and half hours stay for Sind Madrassa-Tul-Islam, on a school matting in Rubie Shield, an inter-school tournament. His record was overtaken by Ikram Elahi, the very next year.

Hanif also represented the Karachi Gymkhana and the Karachi Parsee Institute. It was during a Relief Fund match against the Punjab XI, in which he scored 93 n.o. against Khan Mohammed and Aamir Elahi, he caught an eye of his future captain, A.H.Kardar. In the Sind Pentangular Tournament, he notched up three hundred in as many matches.

He was not yet seventeen when picked to tour England in 1952 for the Pakistan Eaglets. The tour was arranged in order to provide the youngsters with an opportunity to learn and iron out their batting and bowling techniques. The party spent fifteen days at the former Surrey fast bowler Alf Gover’s coaching school. After watching him at the nets, Gover was impressed and added: “I am not going to try to coach this boy and my tip is that you do not let anybody else try it either. He has got everything. He is a natural. All I did was, advise him how to make the best of his perfect technique in the middle.”

Later in the same year, Hanif was opening for Pakistan against the MCC at Bagh-i-Jinnah, Lahore with Nazar Mohammed, twice his age. Nazar has a vivid memory of their first partnership, “When I looked at this frail looking sixteen-year old, I did not think he could cope at this level and I would deliberately take a run off either the fifth or the final ball of the over to keep him away from the strike. But after a little while, to my amazement, Hanif came into the line of the ball with great confidence, that left me in no doubt that he was capable of looking after himself.” The youngster, unused to the natural grass surface managed to bat for almost three hours for his 26 in a ninety-six run opening stand, on his first-class debut. His contribution to the famous win in the second ‘unofficial’ Test at Karachi was a four-hour stay that yielded 64 runs and played a part in his country’s successful 285-run chase. From that series onwards, Hanif was to play the role of a sheet-anchor and used to complement the stroke players, through his great resources of concentration. He was never to be heard complaining about his responsibilities and always followed the captain’s instruction.

Hanif was proving to be a cricket prodigy in the best sense of the word. He was not yet 18 when he accompanied the Pakistan team on their first official tour to India (1952-53). He opened the tour with a hundred in each innings, the youngest ever to perform this feat, in the tourists’ fixture at the holy city of Amritsar. Later on the tour with an unbeaten double hundred against Bombay Cricket Association XI, Hanif easily topped the tour averages. Very few could have painted a better picture of the little opener than Ray Robinson: “When Hanif Mohammed comes in to bat for Pakistan there appears to be little more of him than a sun-helmet, a pair of pads and a dark shadow in between. Somewhere in the darkness under the helmet’s brim, two brown eyes focus with burning intensity on the ball approaching through the heat-shimmering air. The helmet tilts forward as his head goes down to watch the last feet of the ball’s bounce from the baked wicket to the bat. Every line of his neat figure denotes the concentrated attention to the ball necessary to score a double-century at 17 or any other age.”

In his very first Test at New Delhi, he scored 51 in four hours in the presence of Indian Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, but his efforts were in vain as Pakistan suffered an innings defeat. During the third Test at Bombay, he shared a gallant partnership with Waqar Hasan, that almost saved the game for Pakistan. It was after Hanif’s six-hour stay for 96 runs, that prompted captain A.H.Kardar to relieve the youngster of the wicket-keeping duties. There was a general feeling in the Pakistan camp that Hanif would be better off concentrating on his foremost task. Too much was being asked from him, as he would walk out to open the innings, carrying sore hands as a result of his work behind the stumps, which invariably had slipped to sub-standard on the tour. From that day on Hanif would only keep wickets in emergency and was left to devote all his physical and mental energies to batting. It was during the Indian tour that he was dubbed as the “The Little Master”, a tag that to this day is fondly associated with his name.

From the very formative years, his teammates had noticed that it was an impossible task for them to bring Hanif to talk about his batting. He was reluctant to share his methodology and approach on the subject with anyone. Hanif sat for his matriculation exams before the Pakistan team sailed to England for the 1954 tour. Although he achieved little in terms of statistics in the four-match series, he topped the batting averages and showed signs of a rapidly improving opening batsman, who could frustrate the best of bowlers with his water-tight defense. In the first Test at Lord’s, Hanif displayed an impressive temperament, of which England’s wicket-keeper, Godfrey Evans wrote: “Hanif certainly made a great impression on all of us, for during the match he was at the wicket for 340 minutes for 59 runs, a really remarkable performance from so young a batsman on such a bad wicket.” In other fixtures against counties as well he was the most consistent of Pakistan’s batsmen and for the second time running ended with the highest tally of runs among the tourists. He was still in his teens when the tour finished and was singled out as one of the great successes of the tour by A.H.Kardar, although he had a slight concern on the technical aspect of Hanif’s batting. In his tour postscript, he wrote: “Hanif has a crouching stance and this crouch became more prominent on this tour. Hanif never explained it to me but I can guess that by crouching he could adjust his footwork more quickly on wet wickets. But if he is to become great he must give up the crouch and must have an uppish stand. He could also improve his power behind the strokes and his ability to penetrate the field by bringing the lower hand closer to the left one. Kardar was referring to Hanif’s slightly spread grip that had limited him to wristy strokes.

For a young batsman, still in his teens, Hanif astounded his critics with his maturity on his first tour of England. Renowned cricket-writer, E.W.Swanton was one of his many admirers: “Hanif’s method is so neat, his technique in a quite way so admirable, that to watch him is a growing fascination. Hanif makes up for lack of reach by the quick, scrupulously correct use of his feet. The judgment of length is so accurate that Hanif scarcely ever has to move in a hurry, is never off balance. His attacking strokes are made without flamboyant effort, a nicety of timing engendering the speed that beats the field.”

England’s leading bowler Alec Bedser, who bowled to Hanif in the series, gave his impression: “As a batsman, the Indian Sunil Gavaskar reminds me of Hanif. The same oriental patience, the same indifference to time and much the same technique. Perhaps Hanif had an even sterner padlock defense and any bowler getting a ball past him was entitled to think he had done well. Hanif was beautifully balanced, scored heavily behind the wicket with deflections and cuts, and like most small batsmen dealt with the short pitches with hooks and pulls. He was quite imperturbable, unruffled, quite spoken and with a general demeanor to belie his iron purpose.”

Hanif rewrote many batting records during his career and his world-wide reputation was based on his extraordinary feats of crease occupation. After a couple of years’ international exposure, he was widely regarded as the most difficult batsman to dislodge for his remarkable powers of sustained concentration. Although never regarded as a pretty player, the argument often put forward is that the youngster was asked to curb his strokes, in order to become more effective in the fragile batting line-up of the early days. His job remained the same throughout his career, to keep one end going. Like all his brothers, Hanif too will be remembered for his doggedness, for he was seen at his best when batting in against-the-wall situations. His critics often dubbed him as an out-and-out defensive batsman, incapable of increasing the tempo if required, because of his defensive frame of mind. Yet the people who know him closely confirm the fact that at 17, he was full of strokes, though basically a defensive batsman, and that his workmanlike approach was a direct result of his team’s over-reliance on him.

Technically speaking, Hanif was very sound from his early career, although he would take quite a long time to entrench himself. Even in a rare case of an uncertain start, he was capable of holding himself in order not to rush, a quality that was also evident in his off the field mannerism. He had a neat, immaculate air about him to go with his copy-book batting technique. Hanif standing at 5ft.3″ in height and weighing around nine stone possessed great balance to move either back or forward, that is before he suffered a serious knee-injury.

While concentrating on the job at hand, he would go into a shell and anything unusual would upset him.

Shuja-ud-Din remembered his batting experience with Hanif, “During the 1954 tour, I was asked to open with Hanif as the regular opener Aim-ud-Din was not feeling well. While facing Frank Tyson, I noticed that the slip cordon along with the wicket-keeper was standing so far that it was possible to steal a bye while the ball traveled to the wicket-keeper. We decided between ourselves that we would run if either of us was beaten by Tyson. After our two successful attempts, Hanif came to me and said that he is not prepared to carry on like this because it affected his concentration. It was strange to me because despite his intense level of concentration, he did not mind talking in-between the overs.”. He was an absolute professional in his preparation and always had the urge to bat longer and longer, although surprisingly he did not bat more than his colleagues in the nets. Cricket was Hanif’s life and he took great pride in his performance and would be reluctant to throw his wicket away even after getting big hundreds, which was often the case.

In Pakistan’s first Test series on home soil against the 1954-55 Indian tourists, Hanif failed to live up to his reputation. Still, in the second Test at Bahawalpur (142), he managed to reach his first Test hundred. In the next winter against New Zealand (1955-56), Hanif reached a hundred in a rain-ruined final Test at Dacca. In a couple of months’ time, Donald Carr’s MCC ‘A’ team arrived on the tour that was to be marred by the “the water treatment” incident with umpire Idrees Baig. In the first representative match at Lahore, Hanif’s snail-paced hundred did not win him many admirers among a strong crowd of over 30,000.

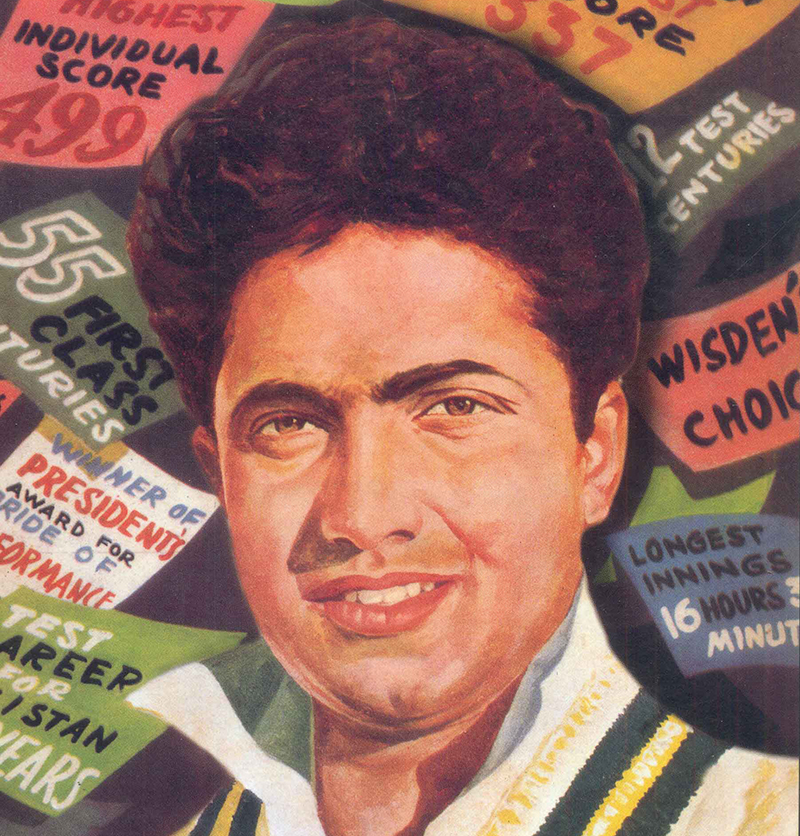

The most memorable innings of Hanif’s career is considered to be his epic 337 against the West Indies in Bridgetown in 1958. He helped Pakistan to avoid an innings defeat against all odds, by occupying the batting crease for a world record 16 hours 10 minutes, the longest first-class innings to this day. West Indies, upon winning the toss had amassed 579-9 dec and skittled out Pakistan for a disappointing 106 all out. The tourists were asked to follow on and Hanif set out his stall and displayed an extraordinary level of concentration, application, and physical endurance in blistering heat He shared in four partnerships of hundred-plus with the first four batsmen that he partnered. By the time he was out to a tired stoke, Hanif had three layers of skin burned away beneath his eyes by the harsh glare reflected from the pitch. With three and a half days’ cricket left, Pakistan through Hanif’s monumental effort was saved from a certain defeat to draw the match. His final score of 337 fell only 27 runs behind the all-time best individual innings of Len Hutton against Australia. Had Hanif overtaken that record, it was quite likely to have survived only a couple of weeks, as in the third Test of the same series, twenty-one-year-old West Indian batsman Garfield Sobers notched up 365 n.o? Sobers, himself one of the bowlers who failed to dislodge Hanif at Bridgetown, summed up the little opener’s simple methodology: “Hanif was a very correct player whose concentration was legendary. He didn’t take many chances. He respected good balls and waited for the bad ones.”

Hanif due to his wicket-keeping experience was one of the better fielders in a poor fielding side in the early fifties. He would be placed in the slips as a safe bet, although it was while in the covers that he inflicted the famous run-out that sealed the Oval Test in 1954. Being a small man and possessing a not too powerful frame, he never had a great throwing arm. And after the cartilage removal operation of the left knee at the end of 1962 tour of England, that kept him out of cricket for almost two years, he could not be considered as a mobile man. In fact in the latter phase of his career, he occupied the slips in order not to expose his handicap.

Although Hanif never bowled his off-spinners regularly at any stage of his long career, he had a somewhat rare ability to be able to bowl with equal effect with both right and left arm. And strangely enough, it was bowling left-arm that he claimed his only Test wicket, P.H.Punjabi of India at Peshawar in 1955.

Although Hanif-mania was at its peak during the series against West Indies in 1957-58, at the end of the tour he had requested the selectors to be dropped down the batting order.

Apparently, despite his triple hundred in the first Test, his confidence had been shattered by the hostility of West Indian strike-bowler Roy Gilchrist. Thereafter Hanif was no longer comfortable with the hook shot and was often seen to take his eyes off the ball, something unimaginable before the tour. Hanif carried the scars of the West Indies tour to the right end of his career, and he was never the same player against extreme pace. His skipper A.H.Kardar expressed his concern about Hanif’s confidence in his postscript of the West Indies tour,” I believe the major reasons for the upset in our batting, particularly in the second and third Test matches came about because of Hanif’s failure to face Gilchrist. In Port-of-Spain and Kingston, Hanif seemed to be running away from the speedster, as he would pull away from lifting balls. His instinct of self-preservation seemed to have got hold of him so much that at the time of the fourth Test he had got into a psychological tangle and was in no mood, despite the placid nature of the wicket, to come to terms with Gilchrist.”

In a year’s time, Hanif was back in the limelight once again, busy piling up 499 on a coir matting, in the semi-final of Quaid-e-Azam Trophy against Bahawalpur. He was run out while trying to keep strike in the final stages of the day’s play, but his innings was the highest individual ever played at a first-class level, and remained so until Brian Lara’s remarkable, 501 n.o, batting for Warwickshire against Durham in 1994. Once again it was through the impregnable bat of Hanif that his country’s name was highlighted in the record books.

Against the touring West Indians (1958-59), Hanif was to appear in only the first Test at Karachi. Having scored a hundred in the first innings, he was forced to retire while batting because of an injured knee. He missed both Dacca and Lahore Test matches.

The 1959-60 Australians, led by Richie Benaud were thwarted by Hanif’s broad bat in the third Test at Karachi. The tourists going for a whitewash failed to dislodge Hanif on his way to yet another priceless match-saving three-figure knock. Qamar-ud-Din Butt’s end of the match report read: “The tourists moved heaven and earth to remove the Little Master which if it had worked would have given them a smooth passage. But as it turned out Hanif, who gives of his best when in a crisis, and Mathias, stayed for long to frustrate Australia’s bid for victory. Hanif, who by inclination hates fanciful strokes, utilised all the resources and mellowed experience to tame the bowlers who were trying for a break through. But when firmly planted, he even played a debonair sort of innings after his fifty was in his grasp.”

In India in the 1960-61 series, Hanif’s continuing discomfort against pace bowling was manifested against Ramakanth Desai. The Indian bowler gave him a torrid time with the rising ball confirming that Hanif’s best years were a thing of past. In the end of the tour report by the Manager, Jehangir Khan, Hanif along with other senior team members were found wanting in their attitude both on and off the field. The report was to be treated as a confidential document, but found its way to India and a section of the Indian press published it. A paragraph on Hanif read, “Hanif’s time-keeping was of great concern throughout the tour and special messengers had to be sent to fetch him every time we had to go to the ground or any other function. This annoyed other members of the team who felt that Hanif was being unduly pampered. If the Manager tried to pull his ears his usual retort was that he should be sent back to Pakistan. His chief grouse, throughout was that being a professional he was not paid the professional fee by the Pakistan Cricket Board. Before the start of the first Test he argued that he was a professional and earned his livelihood from cricket. He was perhaps conscious of the fact that he was more than half of the Pakistan’s batting and could well take advantage of his position. It took considerable time and effort to persuade him to play in the Bombay Test”. Such remarks after an indifferent tour with the bat, were seen as to have dented Hanif’s reputation as a quite-spoken patriotic sportsman.

Hanif’s brief period (1964-67) as Pakistan captain is generally regarded as one of defensive, purposeless and unimaginative cricket. But the fact remains, there was little he could do as he had very limited bowling resources at his disposal and his own batting form was on the decline. On his first overseas trip to New Zealand, he was responsible for some ultra defensive cricket, which did nothing to enhance the reputation of Pakistan cricket. His safety-first approach resulted in some uninspiring cricket that confirmed the common view that Hanif did not want to lose to the lowest ranked team in the world.

In the very first assignment as captain against Australia at Karachi, he had been bold enough to put faith in six players – Abdul Kadir, Asif Iqbal, Khalid Ibadullah, Majid Khan, Pervez Sajjad and Shafqar Rana – making their Test debut. His preference for Khalid Ibadullah, who was especially flown in from England, proved a master stroke as he became the first ever Pakistani batsman to score a hundred on his first Test appearance. Later during the New Zealand tour, Hanif was out cheaply to a rookie left-armer, Richard Collinge for five times in a row for a series of low scores. Hanif’s only success as a captain was achieved against the touring New Zealand in 1965, when Pakistan won two games in a three-match series. In the drawn game at Lahore, he scored the second double hundred of his Test career and dragged his team out of yet another crisis, on a rain-soaked pitch.

On his last tour to England in 1967, in the first Test at Lord’s he played an innings of great merit to earn a draw from yet another possible defeat. At one stage, Pakistan were, 99-6 in reply to England’s 369, when Hanif with solid support from the other end stretched his occupation to more than nine hours. It was his best effort of the tour and his only Test hundred on English soil. His marathon match-saving innings evoked harsh criticism from Michael Parkinson, writing in Sunday Times. He wrote, “In the interests of the game and humanity we should give the Pakistanis the next Test match on condition that they go home immediately and do not return to these shores until their Captain Hanif Mohammed is too old to stagger to the wicket. His tedious display at Lord’s, where he occupied the crease for nine hours, was called a match-saving innings which undeniably it was. What everyone was too polite to point out until now was that he would probably stay the same amount of time and score the same number of runs no matter what the state of the game. You will see my point when the “Little Master”, as he is laughingly called, takes as he surely will when the day comes, seven hours to score a century in a Test match played on a perfect wicket with the opposing side bowling underarm lobs.”

In the rest of the series, Hanif failed with the bat, and that as in the past, resulted in heavy defeats for Pakistan. To relieve the leadership strain, he would lock himself in the hotel room and listen for hours to the twelve tapes of sitar music, he had brought with him from Karachi.

It came as no surprise when he was removed as captain at the end of the tour, on which he did not enjoy the best of health either. Apart from a leg injury, he was suffering from a recurrence of styes on his eyes. It is difficult to imagine how well he would have fared with a set of penetrative strike bowlers in his side. But it is fair to say that he paid a heavy price for being too single-minded, in his approach to the game in general. One cynical remark came from Ian Wooldridge back in 1968, “The total hours that Hanif has been barracked or slow-handclapped around the world may well come close to constituting another kind of record.”

He was also repeatedly criticized in no uncertain terms for his refusal to take even the slightest risk of loss, in order to bring a surprise win for his country. It would be a fair conclusion to say that he was never destined to become the most popular captain to lead Pakistan.

Since his appointment as captain in 1964, Hanif had decided to drop himself from the opening slot and boast the middle order. But against New Zealand in 1969, he was chosen to open the innings with his younger brother Sadiq, in what proved to be his farewell Test, at Karachi. It was only for the second time in the history of Test matches, that three brothers (Mushtaq being the third) were present were picked to represent their country. Hanif could only manage fifty-six runs in his two outings and was asked to call it a day, as his poor left knee had left him with inadequate mobility in the field. He was no longer being looked upon as an automatic choice by the selection committee, headed by A.H.Kardar. A former colleague of Hanif and one of the selectors at the time, Shuja-ud-Din narrated the unpleasant saga: “’Kardar had approached Hanif during the first Test match and on the bases of his fitness, had asked him to announce his retirement. Hanif declined to do so and resented the idea despite having a very poor run in the last two years. But throughout his career he acted as a gentleman and even on this occasion he did not choose to get involved in any kind of vocal outburst. To this day he thinks he was given a raw deal and at the age of 34, could have served the country for at least couple of years.”

On 1st of November 1969, on the third day of the second Test at Lahore that Pakistan was playing without him, Hanif announced his retirement, which he has often referred to as, “forced upon me.”Some sections of the press saw it as reputation-saving act, once he had learnt that he was not to be picked for the rest of the series. It was a sad farewell for a cricketer of Hanif’s calibre, although his intention of carrying on despite his questionable fitness could not be backed up by any great degree of wisdom. At the conclusion of his Test Career, he held virtually almost all of his country’s batting records that included a run tally of 3915, and a number of individual hundreds, 12. He had also appeared in the first 55 out of 57 Test matches for Pakistan having to miss only two games as a result of a hand injury suffered against West Indies at N.S. Karachi 1958-59. It was end of an era tainted by a touch of cricket politics. Although Pakistan lost the very next Test, Hanif was a spent force as far as the selectors were concerned and speculation of a comeback never materialized.

In his school days, Hanif held the inter-school badminton championship, to add to his numerous cricket prizes and was also a keen swimmer. He joined Pakistan International Airlines as commercial agent in the early sixties. In 1994, while serving as sales promotion manager, he retired at the age of 60. He also represented his employees in the first class games from 1961-76, captaining them in all but last season. He also led PIA on numerous tours to East Africa, USA, West Indies, Ireland and The Gulf. Hanif, one of the regular faces at Lord’s Test matches, also played in the Scottish League in the sixties. He was awarded ‘Pride of Performance’ Medal in 1959. In 1968 he was chosen among Wisden’s, ‘Five Cricketers of the Year. Hanif was the chief editor of country’s first cricket magazine in English, The Cricketer (Pakistan) from 1972-90. He held the same position with Cricket Herald. In January 1981, he turned up for overseas veterans against the Indian veterans in Calcutta. He was chosen as Pakistan’s first former Test cricketer to receive a benefit in Sharjah.

After his retirement from first class cricket, Hanif served as a national selector, batting advisor and pitch inspector, for a number of years. He received a great deal of criticism in the media, when he pushed for his son Shoaib Mohammed’s selection. The general opinion was that Shoaib had not progressed at an expected rate and was not yet ready for international exposure. Later on, Shoaib was successful in becoming a permanent fixture under Imran Khan and represented Pakistan in 44 Test matches and 63 one-day internationals. The Mohammed family has played a prominent role in the political power struggle for running cricket affairs in the country. Hanif’s eldest son Shoaib Mohammad, a studious, hard-working and under-rated player, did not need searching for a role model. Now grandson Shehzar Mohammad, 21 is expected to carry on the tradition of the great Mohammad family.

Apart from Shoaib, two of Hanif’s nephews Shahid Mohammed and Asif Mohammed (sons of Raees Mohammed) have represented PIA. Hanif has also served as TV and radio expert summariser on, on and off basis.