Questions about the standard of first-class cricket in Pakistan have been asked since its inception in December 1948. In its embryonic state Pakistan relied more on representative cricket with West Indies, Ceylon and the MCC touring from 1948 until 1951-52. It wasn’t structurally robust; nonetheless cricket in Pakistan was driven by passion and represented by players high on nationalism.

In 1953-54, the BCCP finally decided to put in place the Quaid-i-Azam Trophy, the country’s premier tournament. From 1953-54 until 1970 mostly the first-class matches were hosted by regional or city associations with a couple of department teams taking part. Money, branding, merchandize, remunerations and revenue weren’t the priority, not really understood. First-class cricket was a stepping stone from the players to eventually represent Pakistan. It was an honour having played first-class cricket.

From 1947 until 1970 majority of the cricketers developed from clubs, schools, colleges and universities and they had additional careers to pursue. Cricket was a passion not a bread earner. It was all about the star and the crescent on heaving chests. It was about a green baggy with stars. It wasn’t about endorsements, sponsorships, central contracts, or high financial stakes.

From 1971 world cricket began to see a paradigm shift to a more professional and financially attractive game. Kerry Packer’s World Series cricket changed it all. Vulgar commercialism slowly and steadily engulfed it.

By the mid 1990s, television broadcast rights and huge financial stakes revolutionized cricket’s face. Ironically, Pakistan, supported by departments, took care of players’ financial needs. City associations were the catchment area whilst departmental teams took their final step to break into international cricket.

In the mid-1980s and throughout 1990s Pakistan produced most astounding cricketers. Most of them were the product of overly criticized first-class system. In the 1970s most of the superstars honed their skills in county cricket in England, in the mid-1980s more organized first-class cricket saw some of the top batters and bowlers of the generation being introduced to the world. And then we mucked it up.

BCCP or the PCB, despite being a governing body, was mostly led by handpicked presidents or chairmen. Nepotism, centralized authoritative models of governance, corruption, back-door entrants, and political interventions saw complete administrative and operational erosion. None focussed on developing infrastructure or reinforcing first-class cricket. Commercialism was a reality. PCB needed to redress the issues. Department cricket was their nerve-root since city, provincial or regional teams couldn’t sustain financially. They were dependent on money being poured in by the Pakistan Cricket Board. PCB never ceded their central control. Regional boards never developed.

Ironically, in a state of self-denial led by self-serving chairmen from 2003 onwards with a few exceptions’ PCB failed to live up to the changes that saw world cricket shifting from naturally ordained and flamboyant game patterns to the one more scientifically developed sport.

Top teams of the world reshaped their developing modules, identified the pathways interspersed their coaching with biomechanical, medical, and nutritional expertise. Cricket in Pakistan regressed. Pakistan Cricket Board managements shifted their focus on self-service and instead of incorporating cut for role professionals incessantly collected the sycophants unprofessional or the likeminded. To have full control and brand building through execution of solid policies depended more on image enhancement through social media or by having major stakeholders speaking their language. Honestly, for the last few years cricket governance in Pakistan has been a hogwash.

Pakistan won the Benson & Hedges World Cup in 1992, stunning the hitherto unbeatable England at Melbourne on March 25. To me instead of the world title making us alert to sustain and progress, complacency took over. We had seen the rise of some of the top youngsters turning into stars globally. Corruption and the back-ended intrigues took over. Players became stronger than the management. We saw extreme situations where either the board administrators had their dictatorial presence, or the superstars took them for the ride. There was nothing in between.

Pakistan’s cricket decline started post 2003 and was cyclically complete by the time they lost to Ireland in the ICC World Cup 2007. They did qualify for the finals in the ICC World T20 in 2007 and triumphed in 2009 still living in self-denial. We didn’t invest in the systems that needed to provide our cricket resource for the future. India after losing to Bangladesh and a humiliating exit from the ICC World Cup 2007 re-defined their priorities. They revamped their structure and planned accordingly. India now is a champion team and Pakistan reels at the middle or lower middle of the table.

India down the line are one of the top teams in world cricket. Pakistan by contrast are now in shambles losing back to back one-day internationals to a second-string England. Recent evidence as Pakistan lost to a bunch of country cricketers assembled to represent England after Covid 19 infection rattled their main stock shows where our cricket stands now.

Winning the ICC World T 20 in 2009 or the ICC Champions Trophy in 2017 offered a joyful reminder of Pakistan’s ability to compete at the top of the world game. But then that joy was short-lived. A disaster in England in 2010 saw the more mundane and defensive Misbah-ul- Haq taking control of the team first as captain and subsequently as their Head Coach. With their inability to excel in Tests and One Day Internationals, Misbah and Younis Khan retired, our bunch has come up as T 20 mercenaries. Team bonding and the pride to wear Pakistan colours have seemingly been on the decline.

Franchise cricket and leagues take the preference. But then you can’t fault players when the Pakistan Cricket Board is perennially unable to win the trust of genuine stakeholders, even the players. Some of the cricketers disillusioned and heart-broken have deserted Pakistan looking for opportunities in the United States.

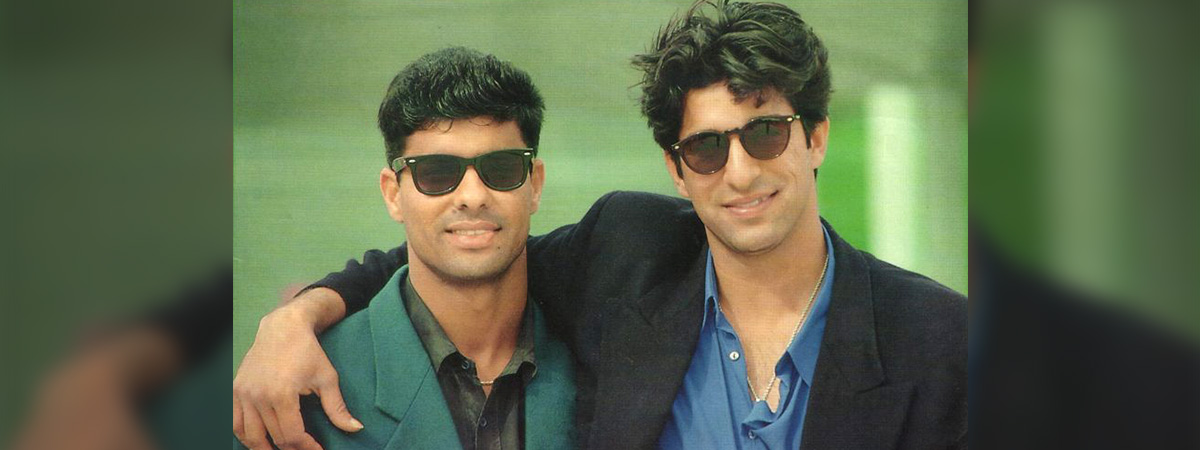

Pakistan were formidable throughout the 1980s and 1990s, as Wasim Akram inherited the team from Javed Miandad and piloted in the era of Saeed Anwar, Aamir Sohail, Inzamam-ul- Haq, Salim Malik, Basit Ali, Rashid Latif, Moin Khan, Waqar Younis, Aaqib Javed, Saqlain Mushtaq or Mushtaq Ahmed.

That period of ascendency, which was made possible due to the perfect combination of natural skill, high self-belief, aura, and talent remains the most remarkable and competitive in our cricketing history.

Regrettably, player-power, the ghost of match-fixing and immature handling or lopsided decisions saw it ending up in a state of chaos. Which makes the challenging times that Pakistan cricket has suffered since more difficult to comprehend. It is sad to see Pakistan cricket the way it is. We were accustomed to see match winners representing Pakistan.

To see the decline is very hard to take. We understand there is going to be a time when you lose players. It was going to be difficult to find another Imran Khan, Zaheer Abbas, another Javed Miandad, another Wasim Akram, another Waqar Younis but we have ceased to grow.

Our cricket is fast becoming irrelevant. We need to come out of the delusion that we have talent. We are starving and personal biases, poor selections and influenced policies are adding problems to all the possible solutions.

The Pakistan Cricket Board seems to be living in illusions. They need to move to the grassroots, to have clubs reactivated and to see domestic cricket set-up run by the people who can make a difference not to have those who are on their right side without having the capacity to produce results. PCB needs to incentivize the youngsters, honestly making their choices ensuring transformation of a new crop into professionally modelled players. Cricket is now a full-time career therefore it has to be channeled properly.

T20 cricket is attractive for the consumers and people who run their franchises but it’s important that the money goes back into cricket and spent sensibly like it happened in India. Indian Premier League redefined the future of their game.

For now, it doesn’t see the PCB headed by Ehsan Mani and Wasim Khan can turn a corner. Even their premier product the Pakistan Super League has been left beleaguered and regressive instead of seeing its outlay doubled.

Now the developed boards in the world have contracted cricketers even the local boys have contracts. That means all the boys from club to city cricket can progress to sustain as high-quality professionals. In three years, we couldn’t even put in place club and city associations and tournaments in place.

The only potential issue is that the last decade’s lost generation means that the current team, featuring talents, are inexperienced and low on modern game’s savviness. Currently most of our players are basically starting their careers and learning on the job. It is going to take some time only if PCB manages to pick the right end of the thread. It doesn’t seem so.