It was John Betjeman who changed the course of his life.

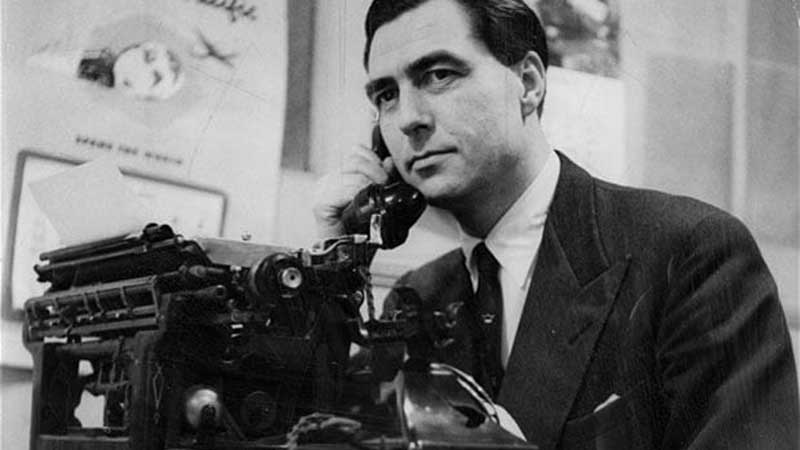

The young man had moved on from his early job as the diet clerk of a mental institution, and was now doing his beats as a member of the Hampshire police force when some of his dreamily ambitious verses reached the accomplished poet. And suddenly, under Betjeman’s guidance he stepped into the shoes of George Orwell.

Well, not in the literal or literary sense. John Arlott became the Overseas Literary Producer at BBC. The man who had held the office before him was Eric Arthur Blair, otherwise known as Orwell, the creator of Animal Farm and 1984.

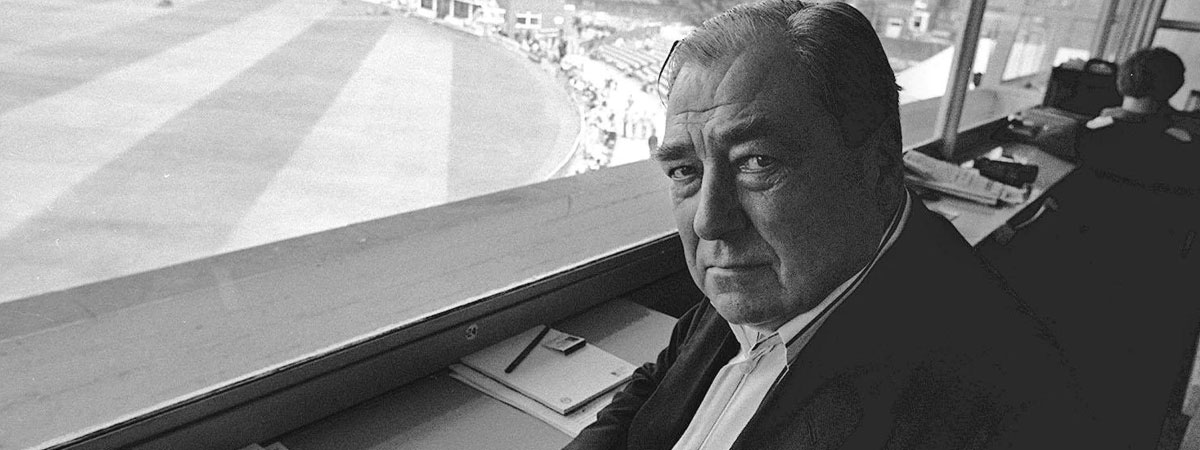

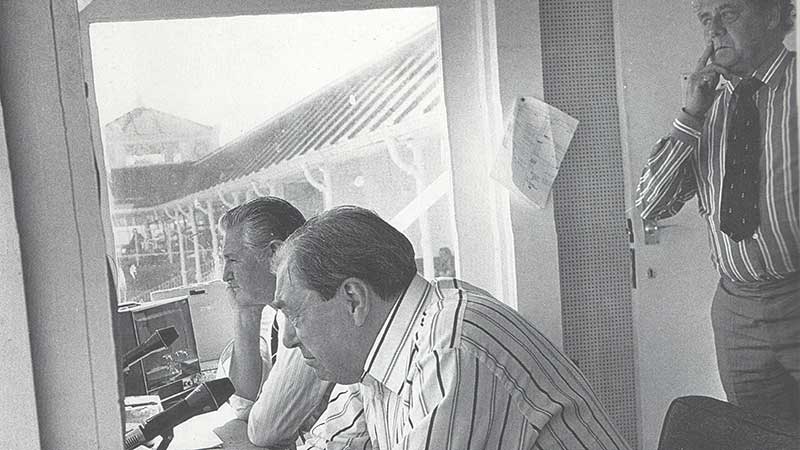

Literary programmes remained a staple for Arlott, even when his voice was ringing through every cricket-loving house of the country and beyond. The poetry, that was so essential a part of his soul, found expression in several collaborations, anthologies … and finally his descriptions from the commentary box.

It was a chance that got him into cricket. That and his fondness for the game.

At a planning meeting Donald Stevenson, head of the BBC Eastern Service, generally asked, “Isn’t there an Indian team coming here this summer?”

It was 1946, and the senior Nawab of Pataudi was about to bring his men over for the first post-War Test series in England. Arlott happened to have a copy of the fixtures in his pocket.

“Have you ever done cricket broadcasts?” Stevenson asked him.

“Yes,” Arlott stretched the truth, banking on a 15-minute talk about Hambledon he had once done.

He was offered the job of broadcasting the Indian tour.

And the voice of cricket began to ring through.

Alongside, he began to host cricketers, inviting them for dinner. Vijay Hazare, Vijay Merchant and Vinoo Mankad were some of the first. Only after they arrived did Mr and Mrs Arlott discover that they were vegetarians who did not even eat eggs. They had to get by on rice and potatoes.

The Indian summer resulted in the first tour book. The following year was the annus mirabilis of Denis Compton. There was a tour book on the South African visit.

And then came 1948. Apart from the usual tour book, at The Oval, Arlott’s voice described the momentous event: “Bradman bowled Hollies … nought …and what do you say under these circumstances?”

The Hampshire drawl had edged its way past the public school accents and stiff upper lip narration. Warmth had entered the commentary box.

Yet, for all the brilliance of his broadcasts and the cadence of his chronicles, it was Arlott the man who made the biggest impact for cricket.

Vijay Merchant had perhaps shaken him out of the cocoon of self-satisfied sense of supremacy that often engulfed the British. Did India really deserve independence in view of the on-going religious riots, Arlott had rather carelessly enquired of the great batsman.

“Shouldn’t the white man stay on to secure peace?”

Merchant had politely reminded his friend that the British had had to undergo a civil war to obtain their own political liberties.

When he went to South Africa in 1948-49, Arlott did describe English captain Frank Mann’s struggle against Tufty Mann as an example of ‘man’s cruelty to man.’ But by then he had become convinced of the equality of all men.

He was having a great time in South Africa … sneaking onto the field during one of the early matches, taking the drinks tray from the twelfth man.

He was popular enough to have newspapers inventing pieces around him. The fictitious pregnant Afrikaner cricket fan Maria Paapenpoel, eager to call her babies after ‘de MCC speelers’.

Expecting twins, she had no difficulty in choosing ‘Eric’ and ‘Alec’ as the two names, obviously after the Bedsers. But in the comic strip, she had triplets. How would she name the third?

“I will call him Yon Arlott after de famous broadkastinger,” she declared without hesitation.

In between Arlott continued to delight with his bon mots. Especially during that fascinating Durban Test.

“Two to win […] that hit him in the stomach, it was passing a foot over and 5000 people appealed and not one came off,”

“127 for 8, neither of them tried the overthrow, I don’t think either of them have sufficient nerve or sufficient wind, and I certainly have no wind at all.”

However, he also saw the dark side that most cricketing visitors were intent on ignoring with eyes wide shut.

Arlott went on a trip to the Black township with the England wicketkeeper and future MCC Secretary Billy Griffith.

“A trickle of stream ran through the middle; they peed into one end and drank from the other,” he recalled.

Charles Fortune, the South African cricket commentator, invited him for dinner. On his way back from Fortune’s place in Grahamstown, Arlott offered to drive his native cook back to her quarters.

They drove through a thunderstorm, and when they got to the squalid accommodation of the African woman, Arlott was shocked. He never forgot the sight. “Shame, hesitation, doubt, guilt struggled in the mind.”

The day he was leaving South Africa, he had to fill a departure form. He left the section marked ‘race’ blank. The immigration officer was not satisfied. “What race are you?”

Arlott looked at him. “Human,” he answered.

“What do you mean?”

“I am a member of the human race,” Arlott’s voice was decisive and his eyes were locked in a staring match, but an inner guardian angel told him that he was not out of the South African jurisdiction yet. A tremor of fear ran through him.

Through his gritted teeth, the officer said, “Get out.”

Arlott was most happy to oblige.

On returning to Britain, Arlott recounted his impressions of South Africa for Meet the Commonwealth on the General Overseas Service. His talk was measured and politically correct for those times, reflecting only on the bright spots.

However, in March 1950, on the Any Questions? radio programme, he lost all restraint:

“Well, rather to my horror—I speak from personal observation in this matter, of course—the existing government in South Africa is predominantly a Nazi one, and most of the present cabinet there, under Dr Malan, supported Hitler during the past war and objected to anybody who had served in the English forces.” He went on to recount how the Zulus had been shot by the South African police during a riot and how in the conservative north “a man who had a car with no brakes ran down and killed a Bantu and his wife was fined, I think, 25 shillings—but it may have been 27 shillings and a sixpence.”

“Anything can happen to a native in South Africa—any form of violence, carrying through as far as murder,” Arlott continued. “And you may rest assured that the person who kills him or ill-treats him won’t suffer in any real way at all.”

A month later, on 21 April 1950, Dr Malan’s government announced that BBC news relays via the South African Broadcasting Corporation were to be banned by 1 July. The ostensible reason provided was ‘politics’, and the example given was John Arlott’s recent ‘Nazi’ comment.

A number of England cricketers, including Denis Compton and Godfrey Evans, condemned Arlott for this ‘tactless’ broadcast. According to Compton, it was ‘hypocritical’ to accept hospitality and criticize the hosts.

The cheerleaders of apartheid were aplenty among the cricketing establishment, influenced by the White bubble of privilege inside which they romped around in the luxuries of South Africa during tours. And, of course, the faithful adherence to the tenets of the Old Boys’ Club.

However, Arlott remained a confirmed opponent of apartheid.

It was to him that Basil D’Oliveira reached out.

Sometime in 1958, the frustrated coloured cricketer penned the first of his now-famous letters, in green ink on cheap, lined notepaper. They were addressed to the man behind the voice that had brought English Test and county cricket to him through the magic of wireless.

He used to hang on to every word he heard on the radio when John Arlott was on air. The voice he heard convinced him that the man behind it was ‘nice and compassionate.’

D’Oliveira wrote to ask whether there was a chance of playing cricket in England for a living.

A couple of years later, a letter from Arlott reached D’Oliveira.

After almost two years of knocking on doors, he had achieved what is virtually impossible—a contract in the Central Lancashire League for Middleton. For just one season the pay was only £450.

“Dear Basil D’Oliveira [sic], Now I have an offer for you to play as a professional in England this summer. But it is imperative that you cable me your decision about it at once. It is with Middleton who for the last two seasons have won the Central Lancashire League. I cannot pretend that this job would be an easy one. You would be expected to bear a fairly heavy share of the bowling through these long afternoon matches, and the professional is normally expected to carry the main weight of the batting too.”

John Kay, the cricket correspondent of the Manchester Evening News, was there to meet D’Oliveira as he cleared immigration. On Arlott’s request, he had taken a day off work to travel down to London.

Kay and D’Oliveira spent the night at Arlott’s London flat.

Through the season, Arlott and Kay discussed D’shOliveira’s fortunes during their weekly phone calls with increasing apprehension. Apart from his progress with Middleton, Arlott maintained a concerned, avuncular interest in the life of the coloured man in a strange, distant country.

A decade later, when D’Oliveira’s inclusion in the England side had divided the cricket world on the South Africa issue, it was Arlott who publicly refused to broadcast any of the matches if the proposed 1970 tour did take place.

When the Stop The Seventy Tour demonstrators disrupted the games of the visiting Springbok Rugby team, they received tremendous criticism from the establishment leaning press of the country.

However, John Arlott wrote: “The demonstrators, by their action against the rugby tour, have in a few months achieved more than the cricket authorities have done by 15 years of acquiescence.”

John Arlott did not just claim that his race was ‘human’. He was human.

One of the rare souls who had the elements so mixed in him, that Nature might stand up and say to all the world, this was a man.

Arunabha Sengupta is the author of Apartheid: A Point to Cover — South African Cricket 1948-70 and the Stop The Seventy Tour Campaign.