Pace is the ultimate weapon in a fast bowler’s arsenal. Whatever skill you may possess of swinging or reversing or seaming the ball, its sheer pace which invokes the adrenalin rush and excitement for players and spectators alike. That is precisely the reason why modern-day England is looking in the direction of Mark Wood or Jofra Archer when encountered with flat tracks in test matches despite possessing the remarkable pairing of Jimmy Anderson and Stuart Broad with quality back ups like Chris Woakes and Sam Curran. That is precisely why Pat Cummins in full flow is a visual delight as compared to his equally prolific wicket taking countryman Josh Hazelwood.

Pace is the reason why the world still fondly remembers the awesome pairing of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson with greater reverence as compared to the more productive duo of Glenn McGrath and Jason Gillespie. It’s all about the difference created by an extra yard of pace. A release speed of 90 mph plus, as compared to a mid-eighties effort, is the one that all the batters hate to face. One would definitely pay more to witness Wahab Riaz’s wicketless molestation of Shane Watson in the 2015 World Cup than a string of wickets by Mohammad Abbas. To borrow from the popular podcast, “Pace is Sexy Yaar”.

Imran Khan in the early part of his career was told and taught otherwise. When he arrived at his county Worcestershire, in true English tradition, he was advised to focus on bowling line and length stuff and he towed that line to control his natural aggression and did not bother about generating more speed. Pace was simply not part of his thinking or plans. Pakistan’s bowling attack at that time was in the hands of a trio of honest medium pacers Asif Masood, Sarfraz Nawaz and Saleem Altaf. Bobby (Saleem Altaf) was the quickest among them but still fell short of being a tearaway quick. Imran’s transformation from a run-of-the-mill fast medium trundle to a fiery pace bowler came in the 1976-77 season which was, in general, a watershed in Pakistan’s cricketing history. Two things happened that accelerated Imran’s change of bowling approach altogether.

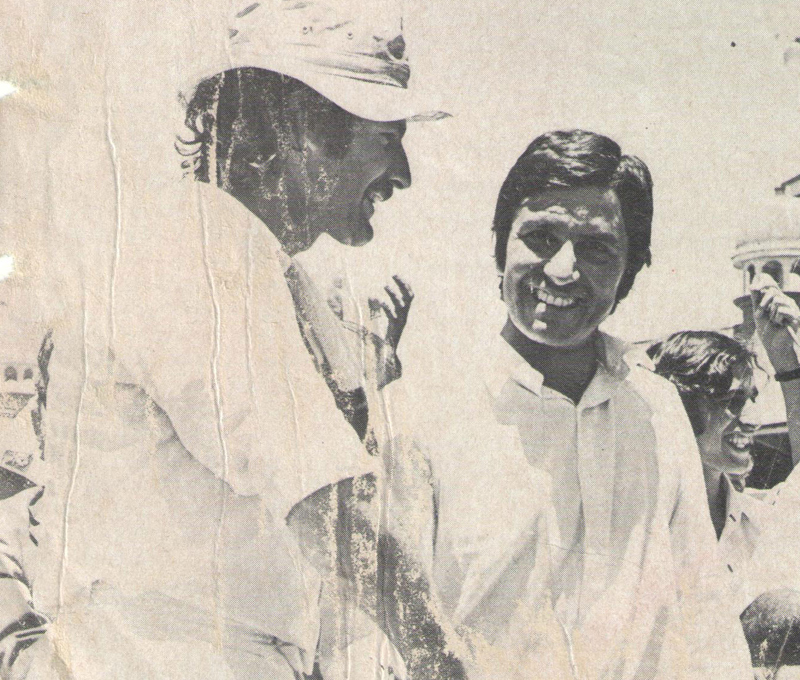

One was his county switch from Worcestershire to Sussex where Imran observed and learnt about the fine art of fast bowling from England’s premier pace bowler of that era John Snow. The other factor was the responsibility given by Pakistan’s newly appointed skipper Mushtaq Mohammad to share the new ball with Sarfraz Nawaz ahead of more established and experienced pacers.

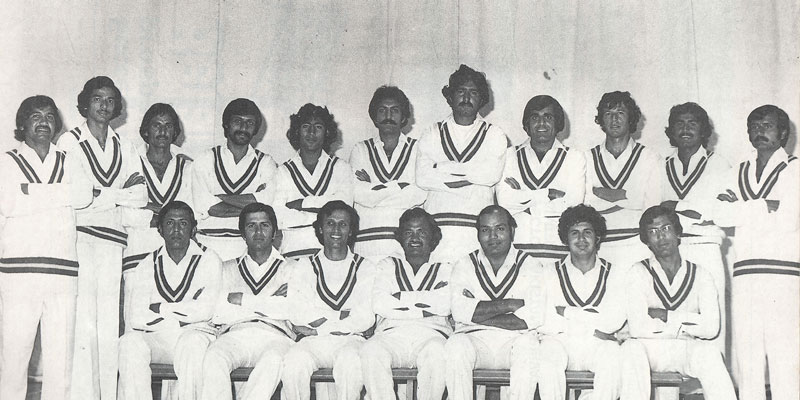

Pakistan’s side started the 1976-77 season with a bang crushing the touring New Zealand team 2-0 and a 3-0 scoreline was only averted owing to a heroic batting display by their wicket keeper Warren Lees and an emerging all rounder Richard Hadlee. Imran collected 14 wickets in three Test matches, only one wicket less than the leading wicket taker Intikhab Alam.

A distasteful controversy emerged during the series based on the pay dispute and Imran was among the players who challenged the BCCP. The intervention to restore sanity came from no less an authority than the then Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the Pakistani side embarked upon for arguably the most arduous and challenging tour of their history to Australia and the West Indies.

In the two previous summers down under, Australians had simply steam rolled their oppositions. In 1974-75 a strong English side were crushed 4-1 after being tormented at the hands of Lillee and Thomson. In 1975-76 the West Indians, who had defeated the Australian side in the inaugural 1975 World Cup final, were pulverized 5-1 with the added venom of left armer Gary Gilmour into the Aussie attack. Pakistanis were considered a mere push over to even greater glory for the Australian juggernaut. In a horrifying start to the tour a young Western Australian side defeated Pakistan. A brilliant unbeaten knock of 143 by Kim Hughes who smashed Pakistan’s four pronged pace attack underlined Australia’s bench strength.

The first Test at Adelaide lived up to the predicted script till late in the fourth evening when Pakistan’s ninth wicket fell and they were just 197 runs ahead. The only blip for Australia was an unfortunate shoulder injury to their premier strike bowler Jeff Thomson. In walked the debutant spinner Iqbal Qasim to join Asif Iqbal who was not in prime form. An 87 runs last wicket partnership between the two stretched well into the final day and deflated the Australians a bit. While chasing Aussies lost their sixth wicket after tea on the final day and Rod Marsh and Gary Gilmour were advised by the team management to bring the shutters down and were booed by the local crowd for not going positively at a very reachable target.

Normalcy was restored when Pakistanis were rocked by Dennis Lillee in the New Year test match at the MCG. They sank to an ignominious 348 runs defeat early on the fifth morning. This ominously dark cloud had a silver lining. In absence of Sarfraz Nawaz owing to an injury, a 24-year-old Imran was entrusted with the spearhead role. He was spanked for a 100-plus wicketless return as Australia amassed a 500-plus score built around hundreds by Garry Cosier and Greg Chappell. Then came the turning point. Finally, the tiger was unleashed. Imran decided to bowl quickly in the second Australian innings, liberating himself from the steady and accurate medium pacer mindset. This immediately yielded results in the shape of Imran’s first Test match fifer as he carved out the heart of Australian batting including both first innings centurions.

Before the final Test at Sydney Pakistan also had the misfortune of running into a rampaging and inform Viv Richards who stroked a delightful hundred for Queensland. Imran eventually dismissed Richards and gave a good account of himself whereas the rest of the attack was just pedestrian. Pakistan arrived at Sydney with the historical baggage of one of their most painful defeats on their last expedition to Australia four years ago. Chasing a meagre 159 runs target Pakistan collapsed inexplicably on that fateful final morning and the whole side crashed for just 106.

Greg Chappell won the toss and elected to bat on a wicket that he considered would crack in the later part of the game and after Adelaide, he was quite wary of the spin prowess and variety available in the Pakistan camp. In addition to newcomer left-armer Iqbal Qasim there was the part-time unconventional leg-spinning duo of Mushtaq Mohammad and Javed Miandad which prowled on Greg’s mind. The fact that Pakistan was going into this test match with just two front-line seamers Sarfraz and Imran underlined his firm faith in his batting lineup and highlighted the defensive mindset of the tourists who played with seven frontline batsmen.

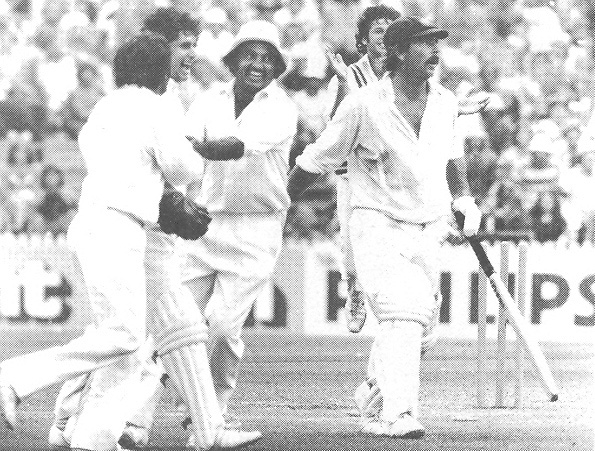

In just over an hour after the start of the test match, the Australians found themselves reeling at four down for 38. These opening wickets were equally shared by Imran and Sarfraz. While Sarfraz was his usual canny self, Imran was a model of hostility and sheer pace. For once the famed batting lineup of Australia was crumbling against an unlikely opponent dishing out doses of their own medicine.

Aussie skipper Greg Chappell briefly restored some sanity when he stitched together a partnership with Cosier which took Australia into three figures. Imran returned for his second spell to remove both of them and at one stage Aussies were 9/159. Lillee and Max Walker staged the second mini rearguard to take Australia beyond 200 and finally it took a Javed Miandad top spinner to conclude their innings. Imran had taken 6 for 102 and was ably supported by Sarfraz who snapped up 3 wickets.

Majid and Sadiq bore the brunt of Australia’s opening burst putting on 42 before wickets at regular intervals brought Pakistan to a nervy 111/4. Enter Asif Iqbal, the proven man for such a crisis, and what a masterly knock the Kent cavalier played in the company of debutant Haroon Rasheed and teenager Javed Miandad. Together they blunted every weapon of Lillee, Gilmour, and Walker and Pakistan ended up with a healthy and possibly match-winning lead of 149 runs. Asif’s 120 was worth its weight in gold as it did not let Imran’s performance go to waste.

Imran needed to prove to all and sundry that his first innings fireworks were not a fluke. The wicket had eased out and yet when Imran was operating at the top pace it looked an entirely different piece of turf. The Australian openers were more circumspect and batted steadily to reach 32 when Sarfraz broke through by getting Alan Turner. From there onwards it was Imran who sliced through the remaining batting line and at one stage Australians were 8/115 and in serious danger of succumbing to an innings defeat. They found no answer to Imran’s sustained aggression which was well supplemented by the wiles of Sarfraz. The ninth wicket pairing of West Australian couple of Marsh and Lillee took their team past the innings defeat mark and when Marsh was run out at the fag end of the day Australia was only 31 runs ahead.

A rest day followed and the entire Pakistani populace was delighted by Pakistan Television’s decision for the live broadcast of the fourth-morning play anticipating a quick Pakistani win. Such live coverage was a rarity in those days and was generally reserved for Field Hockey finals and Boxing bouts of Mohammad Ali. Fittingly it was Imran who took out Lillee with another snorter without an addition to the score and completed his second haul of six wickets in the match. Lillee did spoil Pakistan’s party by bowling a nasty little spell and taking out Sadiq Mohammad and Zaheer Abbas quickly and also making skipper Mushtaq hop around the crease.

But all old ghosts of Sydney 1972-73 were laid to rest by Imran’s cousin Majid Khan whose effortless pull for six can still be found on the internet. A silky cover-driven boundary off Max Walker settled the chase and Imran’s name was firmly etched as Australia’s conqueror in the annals of Pakistan’s cricketing history. It was Pakistan’s only fifth win abroad in 25 years of Test cricket and laid the foundation for many more to come.

Sydney remains the birthplace of Pakistan’s pace legacy. With no disrespect to legends like Fazal Mahmood, Khan Mohammad, and Sarfraz Nawaz, Imran was the pioneer of express bowling in Pakistan. He became an inspiration for the generations who followed in his footsteps with varying degrees of success. Some even exceed the master himself like his prodigies Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis.

The 90 mph plus club of Pakistan continued in the shape of tearaways Shoaib Akhtar, Mohammad Zahid and Wahab Riaz and the future appears to be safe in the hands of an emerging young duo of Haris Rauf and Mohammad Hasnain.