In a long cricket career, which I owe mainly to my ability to turn up on time, I have done much of my best work in the nets.

I have practised my arts in nets indoors and outdoors, in all conditions, in temperatures from 0 to 50 Celsius, in over twenty countries, including Pakistan in my twilight years.

There is a very different atmosphere to any net practice in Pakistan to that in the lower depths of English cricket.

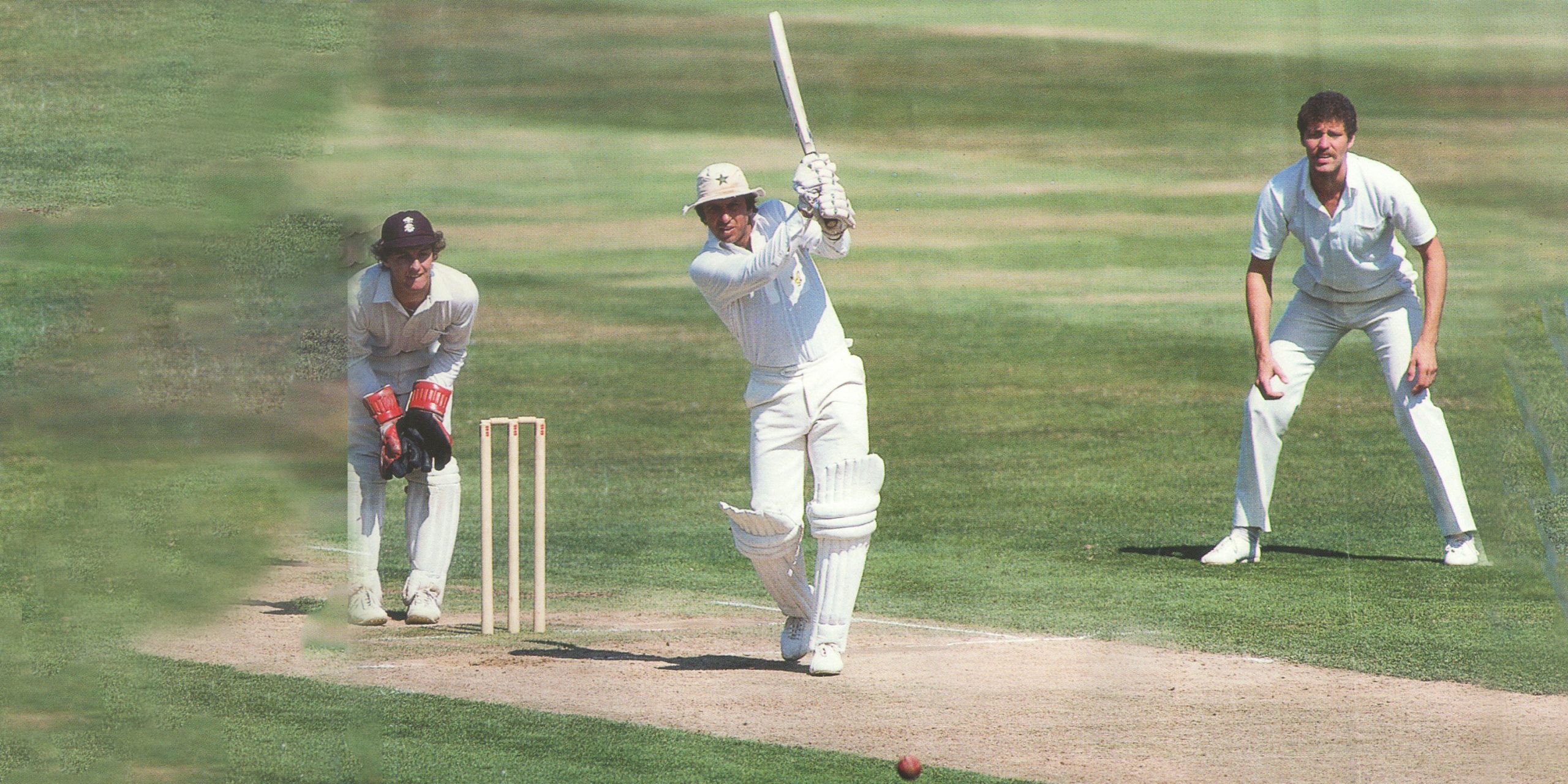

In Pakistan I have found that a net is always a serious business. The visitor is invited to bat against a variety of bowlers, who believe that it is only good manners to serve up their best deliveries. Many will be seeking elevation to some upper level of cricket – and with good reason, since Pakistan has such a rich history of young players discovered in net sessions.

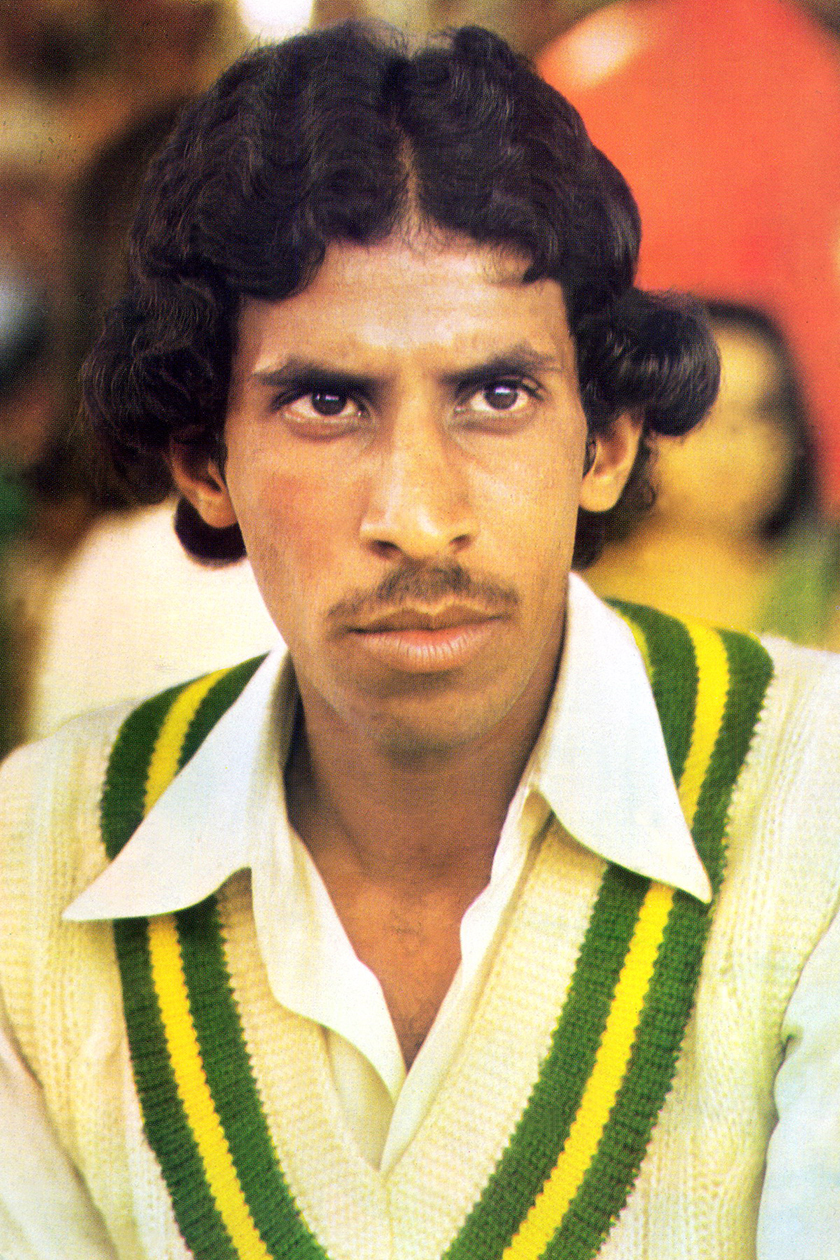

Some years ago, I had the joy of meeting Tauseef Ahmed, the inspiration for net bowlers all over the world. I heard him tell the story of being plucked from club cricket in Karachi in 1980 to give more practice against off-spin to Pakistan’s Test team facing the visiting Australians.

So well did he bowl against a batting line-up including Javed Miandad, Majid Khan, Zaheer Abbas and Wasim Raja, that he was called into the Test team. He had to borrow all his kit, including a pair of boots a size too small.

Defying their obvious torment, he proceeded to take seven Australian wickets and launch a career of 34 Test matches and 70 one-day internationals (he was at the other end when Javed Miandad hit his legendary six to beat India in Sharjah).

The visiting batsman will probably face bowlers from older and younger generations, but these offer no relief from the would-be Tauseef’s. The older bowlers will nearly always retain skills from a higher level of cricket, while I have always found it embarrassing to face a bowler of 10 or 11 years in Pakistan, who is either the next Wasim Akram in waiting or the next Abdul Qadir.

However, it is always good to witness their joy at dismissing me. I continue to hope that I might read about this experience in a profile in ScoreLine when one of them becomes famous: “I really started to believe in myself when I clean-bowled the experienced English batsman Richard Heller…”

Things get no better for the visitor when he has a bowl in a Pakistani net. Local batsmen will again think it good manners to perform at their best. It is painful to be driven, cut, forced, flicked, glanced or swept at will. Even more painful is to realize that a rare defensive stroke was not for a good delivery but the batsman’s decision to have a moment’s rest.

My usual nets in England are conducted very differently.

No one expects to be discovered there. In fact, any cricketer with pretensions would be embarrassed to be discovered there.

Net practice rarely if ever translates into match performance and that is not its purpose. Apart from the social life afterwards, people go to our nets for an excursion into fantasy. Free from match pressure, ignoring dismissals as a batsman and carnage as a bowler, it is that much easier to express yourself.

You are far more likely to enjoy that elusive moment when you do something absolutely right, exactly as your idol would have done in some great arena. (My own moments of this kind are now accompanied by an imaginary Karachi crowd chanting “Wah-Wah!”)

It is especially easy to bowl in nets because there is no penalty for being hit for six, even when it happens over and over again. You do not sense the spirit leeching from your teammates and supporters, or hear them counting the balls to the end of the over. You do not hear the muttered curses and the unmeant encouragement and the fatuous instructions to relax. When you are hit for six in nets, you have simply given a friend a moment of ecstasy.

Some years back, I built a small business for myself as a batting therapist. The therapy consisted simply of bowling at out-of-form batsmen in the nets. My bowling then was just about good enough to require a certain amount of vigilance but most of it said “Go on, you can hit this!” A few overs of this therapy nearly always restored a batsman’s self-esteem. I am especially proud of teaching many children how to straight drive. My stuff tends to be well-pitched up and if they remember my magic words “Feet move, head still” they can regularly propel it over my head into row Z of the spectators.

At low points of my life, cricket nets have been a place of refuge, where for an hour or two I could be a different person in a different world. I would roll up and bowl to anyone and everyone, or no one at all, at anything the same rough size as a set of stumps. I often met others on the same mission.

We would go through the fiction of pretending to wait for others and offer to bowl or bat against each other “while you’re waiting.” Some became friends and team mates, others disappeared, but for a short time we would sustain each other’s fantasies.

I wrote my second cricket novel on this theme. The Network (ha-ha) begins in the cricket nets of a London Park, haunted by a lonely teenage bowler. His life and prospects are desolate, but he clings to his dreams in the nets and the people he meets there make them all come true.

I must have bowled a decent spell when I thought of it.