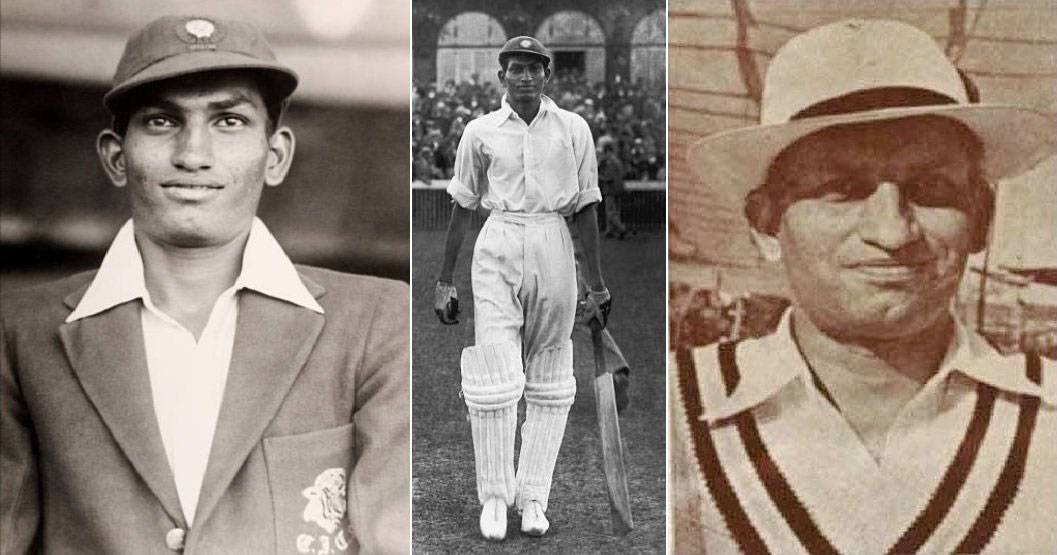

The dichotomy between how and how much… The debate between the relative worth of beauty and substance. This was never as much up for discussion as when the blade of Mushtaq Ali flashed in all its genius.

Never more when he scored the first ever overseas Test hundred for India and left the field that day unbeaten on 106. Waiting for him, all smiles and admiration, was the great friend of the late Ranjitsinhji. “Ranji would have been the happiest man,” CB Fry remarked. The likes of Jack Hobbs, Douglas Jardine and Plum Warner were there too – men of differing characters and ways of expression, yet the effusiveness of their praise remained identically lavish.

Even a cricketer famed for his taciturn nature, Wally Hammond, had been moved by the strokeplay Mushtaq had unleashed at Manchester that afternoon. Gubby Allen had bowled fast and outside the off stump, trying to lure the lanky Indian opening batsman into a false stroke. And Mushtaq had continued to pull him to the leg side boundary. When he had entered his 90s, Hammond had walked over to him. “My boy, be steady, get your hundred.”

Mushtaq did. Vijay Merchant was on 79 at the end of the day. India trailing by 368 when they went in to bat the second time, were on 190 without loss.

Captain Vizzy, who had instructed him to run Merchant out when they went in, had also been smitten by the spectacular innings. He forgot all about the youngster disobeying direct orders and gifted the 21-year-old a gold watch.

He fell for 112 the next day. Merchant went on to score 114. The Test ended with India safe and secure on 390 for 5. And Neville Cardus, that celebrant of beauty, wrote his famous and rather meaningless remark which has forever been a shield for fact-shunning, number-ignorant fans and chroniclers of cricket: “There ought to be some other way of reckoning quality in this best and loveliest of games: the scoreboard is an ass.”

It is hardly a surprise then that he was immensely popular in Calcutta. At the Eden Gardens batting artists such as GR Viswanath, Mohammad Azharuddin and VVS Laxman produced some of their best innings and remained forever the idols of that cricket-romantic city. It was the Calcuttans who raised the ‘No Mushtaq No Test’ cry when he was dropped by the selectors; it was the Calcuttans who forced his return to the side.

They had every reason to love him. Set 431 against West Indies in 415 minutes, India were not expected to go for the runs. Neither did they in the final assessment, finishing on a strong 325 for 3. But Mushtaq had the imagination to believe that the impossible was attainable. He hit 106 out of 154 before he was trapped leg before, the upraised finger cruelly piercing innumerable hearts. With him gone, Vijay Hazare and Rusi Modi continued the journey to safety, with class and mastery but without the heady, bohemian genius that hinted at extending the boundaries of possibility.

“If Mushtaq comes to the West Indies he will be idolised,” said Prior Jones.

Those were his only Test hundreds. He scored just 612 runs in 11 Tests at a modest 32.21. But when he was in full flow the cuts, drives and pulls were essayed with a silken touch that brightened the day for the thousands who cheered.

But as the average indicates, those days came once in a while, unlike the Hazares, Merchants and Modis for whom scoring runs was a way more consistent, way more profitable, endeavour.

He averaged just 35 in first-class cricket, compared to the stratospheric figures amassed by the Hazares, Merchants and Modis.

Yes, he did have a long long first-class career. The numbers, however, bear testimony to his longevity as well as frailty.

Mushtaq batted in 384 innings and notched 30 hundreds – once every 12.8 innings. Merchant batted 234 times and hit 45 centuries, one hundred every 5.2 innings. Hazare’s 367 brought him 60, one century every 6.12 innings.

Modi batted just 154 times and raised his bat on 20 occasions – a hundred every 7.7 outings. Only 6 times did Mushtaq pass 150 in his career (once every 64 innings he batted), compared to 29 times for Hazare (once every 12.65 times), 21 for Merchant (once every 11.14 times) and 11 for Modi (once every 14 times).

Mushtaq was not an accumulator like the rest. He was an entertainer. He came off less often than those magnificent batsmen of Indian cricket. But when he did, the spectators, who suffered many a heartbreak when he perished, did witness the unforgettable.

In early 1980 Mushtaq was 65, a guest of honour watching the Jubilee Test between India and England at Bombay. On a grassy pitch, faced with Ian Botham and John Lever, Sunil Gavaskar and Dilip Vengsarkar unveiled a repertoire of uncharacteristically aggressive strokes in the very first session of the match, the former even clearing the fence once. The score rattled up past 100 in the morning before both of them perished to avoidable snicks. When asked about his quickfire 49, especially about what made him throw caution so unusually to the winds, Gavaskar responded that he was influenced by the presence of the legendary Mushtaq Ali in the stands.

True, sometimes even the personification of substance can bow to the legend of style.