Author Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, KBE (P. G. Wodehouse), comic novelist, short story writer, lyricist, and playwright, best known as the creator of Jeeves, the supreme “gentleman’s gentleman”. Most probably this character was based on the ideology of what a cricketer should be like. Wodehouse was a die-hard cricket lover whose every book or novel had some mention about the game of cricket and the gentlemen characters of the sport.

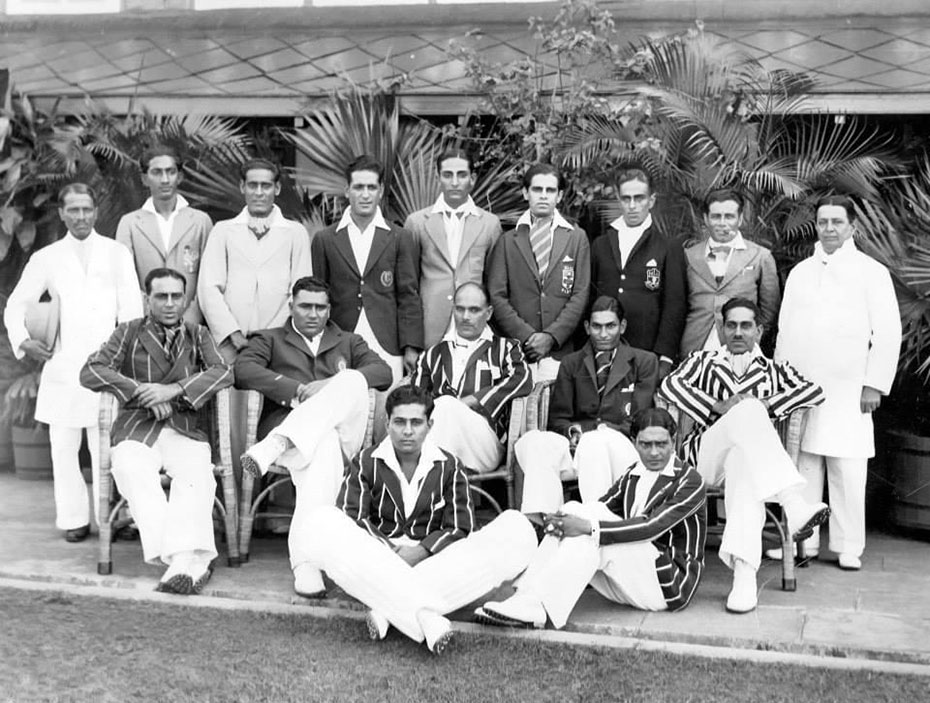

When India sent the first-ever cricket team of the Sub-Continent on its maiden tour of England in 1932, a Wodehouse book-like character in the form of Mohammed Nissar was on the team. He stood at 6′-3″ and weighed 250 lbs. He had dark complexion and when he ran in to bowl, according to the great cricket Umpire Frank Chester the earth rumbled under his feet. Others would say a black locomotive is charging at full steam.

On the tour of 1932, they played a total of 37 matches, out of which 26 were first-class matches. The visitors won 9 of the first-class games and the credit for that was given to C. K. Nayudu and the two fast bowlers Mohammed Nissar and Amar Singh.

It is noteworthy that Munshi Premchand the well-known writer has also written about cricket in his literary works. He wrote an account of the Indian cricket team’s tour of England on October 12, 1932, in an editorial published in ‘Jagran’. He wrote, “The Indian cricket team may not have achieved as much success as the Indian hockey team, but its successes were still significant. The performance of the Indian players showed England that India cannot be neglected even in the field of play. The truth is that the people of India can beat the world if they get opportunities, in every sphere of life. The people of England take pride in cricket but the 1932 tour made them wake up to the talent of the players of the Sub-Continent. It is a matter of joy that the Viceroy honoured the Indian team and introduced himself as a gentleman.”

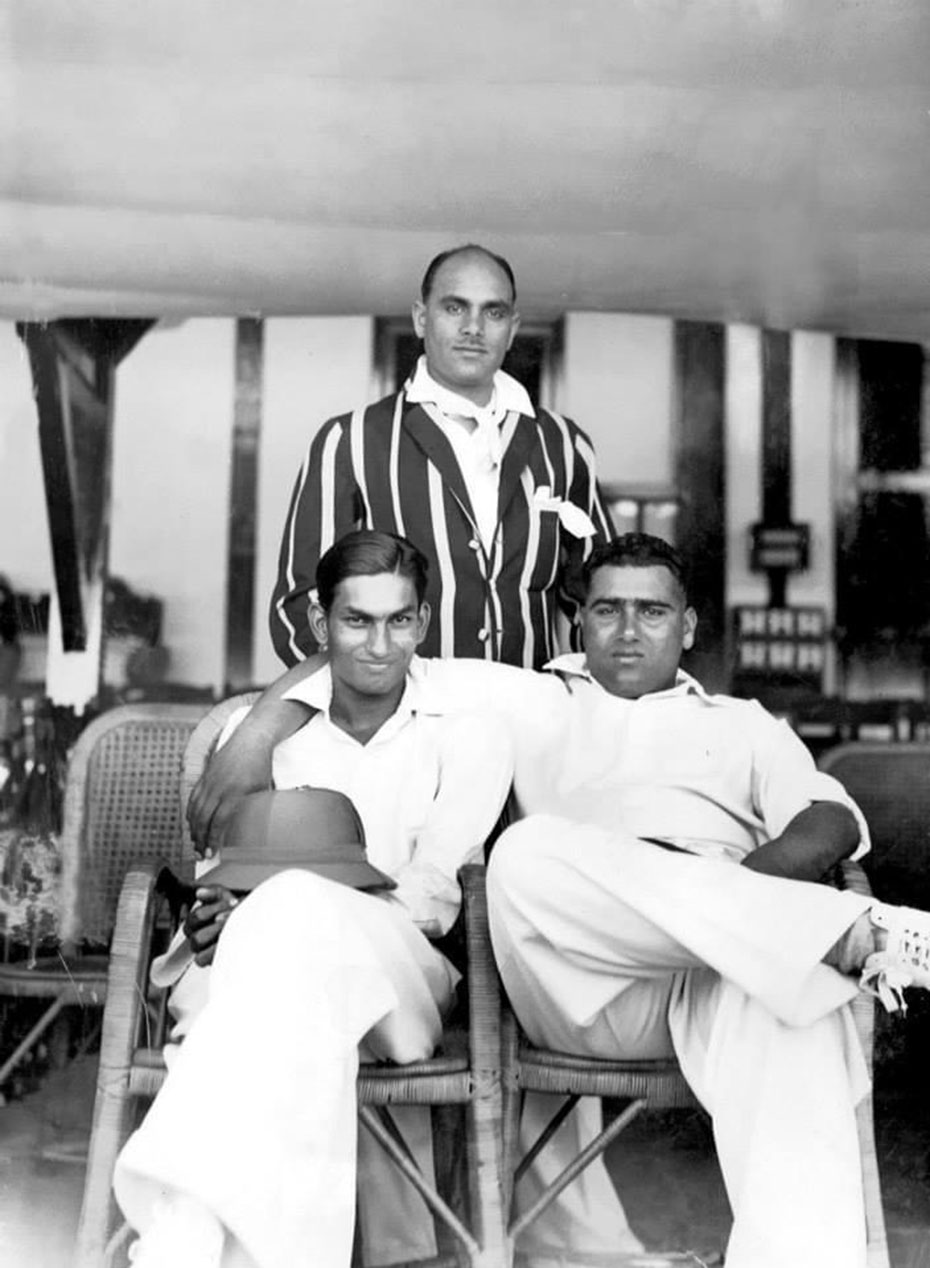

According to the All-India all-rounder Dr. Jahangir Khan (father of Majid Khan and uncle of Imran Khan), who played India’s first 4 Tests, “Nissar was a magnificent bowler and a great sportsman, who was an asset to any team of his time. A great slip fielder who could bring off surprising catches in spite of his weight. I have not seen a faster bowler than him in this sub-continent.”

India’s first Test captain C. K. Nayudu, believed that Nissar was quicker than England’s notorious and legendary bowler Harold Larwood, who was widely believed to be the fastest bowler in the history of cricket. Having faced both bowlers in his career, Nayudu knew who was faster. “Early in his spells, Nissar was quicker than even Larwood.” Nayudu made the statement after the inaugural Test in which both the bowlers had played.

India’s first great batsman Vijay Merchant paid the highest tribute to Nissar when he said, “What a great fast bowler he was! He was the best and the fastest I have ever played against. In my time I played against Larwood, Voce, Bowes, Allen, and Gover. The first two were past their best when I played them and the other three did not come up to the standard of Nissar. I have not seen a more accurate bowler.”

Under the auspices of the Carson Institute of Pakistan Western Railways Lahore, which was known as one of the foremost nurseries of cricket, S. M. Nissar Memorial Invitation Cricket Tournament was inaugurated in 1965 to pay homage to the memory of the late Mohammad Nissar. The tournament was held yearly till 1967. It was abandoned in 1968 but was revived again in 1969 and continued till 1972.

Vijay Merchant sent a special message saying, “Truly a great cricketer is being honoured thereby, because in my 22 years of first-class cricket I never came across a greater fast bowler than this towering personality from Lahore. Mohammad Nissar was one of those few fast bowlers whose aim was to hit the stumps and not the batsman. He bowled between the wickets more than any fast bowler I have played and was as accurate as any bowler I have seen, fast or medium. We from the South could never master him and the only occasion, on which I made a score against him, I shall cherish because even when things were going wrong against his team, he never bowled a bumper or tried to hit the batsman. The likes of him we have never seen again in India and I doubt very much if Pakistan has either. It was a pity that there were not many Test matches during this time, otherwise, Nissar would have proved himself to be one of the greatest fast bowlers. It was a privilege to have played with and against him.”

Pakistan captain A. H. Kardar recording his message on this occasion said, “I feel honoured in joining to pay homage to the memory of a great cricketer and welcome the holding of the S. M. Nissar Memorial Cricket Tournament. Although my own cricket career dates from the time the late Mohammad Nissar retired from first-class cricket, yet there was a Festival Match in which I had the good fortune of seeing him in action. I had good luck, though, not to face him. He had plenty of fire in him even then because he bowled a few overs. In those overs he accounted for the wicket of the prolific opener Nazar Mohammad. I could visualize his speed in his younger days, amply borne out by the many fine bowling achievements of this great fast bowler. He was in the class of the great fast bowlers of an era, which boasted of all-time greats, Larwood, Voce, Bowes, Gubby Allen, Constantine, Martindale, etc. It is a pity that he lived in an age when film records were not maintained.

However, it should be possible to bring out a special Nissar Number with the contributions of his contemporaries still alive in the sub-continent. I think the venture is essential so that the record of the late Nissar’s achievements may be maintained to inspire and be a source of joy to the coming generation of cricketers. I commend the publication to the organizers of the Tournament and trust that it will be possible for them to release the Special Nissar Number at the time of holding the next Tournament.”

Mohammed Nissar was India’s first pace bowler and arguably still the fastest ever to play from the Sub- Continent. He played in India’s maiden Test against England at Lord’s in 1932 and has the distinction of bowling the first delivery, and also taking the first wicket by a Sub-Continent bowler.

In the first innings, he shattered the English batting by taking 5 wickets for 93 runs. In his opening spell he knocked over the stumps of Percy Holmes and Herbert Sutcliffe, who had a 555 runs partnership for the first wicket for Yorkshire against Essex only ten days earlier. His first ball for India in Test cricket was at a pace that shook the world making them sit up in their Long Room and take notice. Within the first few minutes on that day at Lord’s, Nissar, with the first ball of his second over dismissed Herbert Sutcliffe for 3, knocking over his stumps playing on to a scorching in-swinging yorker.

Soon after, with the fifth ball of the same over, he sent the off stump of Percy Holmes in a spectacular cartwheel with one that came back viciously like a serpent. England’s score stood at 11 for 2. On that tour, 21 years old Nissar, swung and cut the ball at a fiery pace to take 71 wickets at 18 runs apiece.

More than half his international wickets were either bowled or leg before wicket, a testimony to his sheer pace. India’s first opening batsman Jeoomal Naoomal who played in the first 3 Tests for India and was a teammate of Nissar maintained that “Nissar never bowled to intimidate a batsman with the new ball. He never sent bumpers. His target was the stumps and he always bowled between the wickets.”

Naoomal later on gave guidance to players like Hanif Mohammed, Saeed Ahmed and Fazal Mahmood in Pakistan. The celebrated Indian batsman Syed Mushtaq Ali believed Nissar to be the greatest fast bowler ever.

Mohammed Nissar, although belonging to Lahore, he was born in Hoshiarpur in East Punjab on August 1, 1910 in the house of his maternal grandparents. Nissar’s father, Sheikh Ghulam Mohammed lived and worked at the Al-Riaz estate of Mian Ghiasuddin in the Old Civil Lines area. It was at this vast estate which was located around Cust Road behind the Central Model School on the Lower Mall, and the by-lanes of Tap Road and Rattigan Road where Nissar started playing cricket. He had two brothers and two younger sisters.

Mian Ghiasuddin’s son G. Mueenuddin was a well-known civil servant who is attributed to the Indus Water Treaty with India. His son Mian Riazuddin, a friend, had married the daughter of the Indian cricket captain, Nawab Iftikhar Ali Pataudi and was a brother-in-law of cricketer Tiger Mansur Ali Pataudi. The Veterinary College, DAV College, The New Hostel of the Government College Lahore, Bradlaugh Hall, and the Superintendent of Police Office were all located in close proximity to Al-Riaz.

In December 1929 a gruesome drama unfolded in this area when Bhagat Singh and Rajguru shot dead a 21 years old police officer ASP John Sanders mistaking him for a British Police Superintendent James Scott. Sanders was shot eight times from within the DAV College. They believed Scott was responsible for the death of the nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai by having ordered a baton charge to disperse a rally taken out in Lahore to condemn the Rowlatt Act.

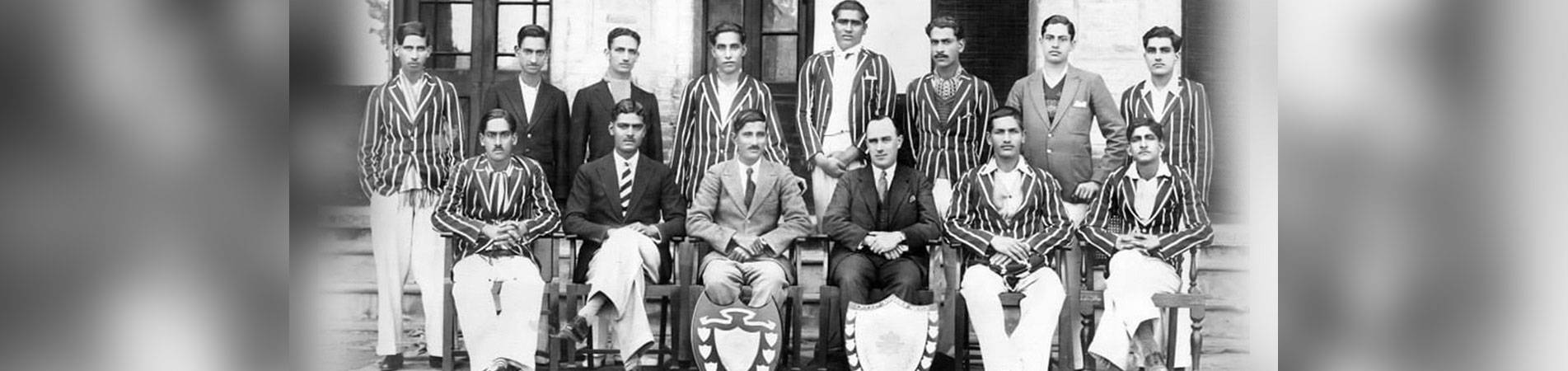

Nissar represented the Punjab University for the first time in 1928 and the same year represented the Muhammadans in the Punjab Quadrangular. He met with immediate success and secured 3 wickets for 5 runs. In his 3rd year at the Islamia College, Nissar moved over to the Government College Lahore, a change that brought much development in him as a cricketer. Earlier he had played in Prince of Wales College, Jammu as an opening batsman. His performance in the Inter-Collegiate tournament final of securing 9 wickets in each innings brought him much recognition.

However, after the match, he was spitting blood for four days. The exertion of bowling unchanged throughout the day undid him and he was hospitalized for a week. After this scintillating performance, Nissar was only 21 when invited to Patiala for trials for the 1932 tour. He took 3 wickets there and was asked for another trial at Lahore where he took 6 for 68 to ensure his inclusion in the touring team.

On his second tour of England in 1936, Nissar took 137 wickets in all first-class matches at an average of 21.4. Nissar reached the pinnacle of his career against Jack Ryder’s Australian team in 1935-36 by capturing 32 wickets in four unofficial Tests at an average of 12.9. Ryder described him as one of the best fast bowlers in the world.

Sir Don Bradman commented, “Two great Indians never to visit Australia were Nissar and Amar Singh, but my Test selector colleague and Test Captain Jack Ryder played against them in India. Many nights I sat with him into the small hours being enthralled listening to his stories of their skill.” Neville Cardus described Nissar saying, “Nissar’s speed during half a dozen overs was really capital. In every over, we saw half-hit defensive strokes, untidy, uncertain.” Nissar stood at No. 9 in the world ranking at the time. More than half of his victims in international cricket were either bowled or lbw, a testimony to the sheer pace at which he came at the batsmen.

Nissar never expected pampering or sought a special status even at the height of his fame. The Government College Lahore cricket team, which he eventually captained and won the University Championship, was leaving for Delhi to play a few friendly matches.

Having just returned from the English tour, Nissar came to know about the trip and enquired if he could accompany the team. The team members told him that it was not a tour for a cricketer of his stature as they would be traveling in third class and may not be able to lodge him decently in Dehli (now Delhi). Nissar would hear nothing of it and traveled with the team. Their stay at Feroz Shah Kotla ground lacked basic amenities but Nissar had no complaints and said, “I have come to play cricket and not enjoy luxuries.” Nissar played in the Ranji Trophy for Southern Punjab and the United Provinces. He represented Muslims in the Bombay Pentangular tournament.

Nissar’s final Test at the Oval in 1936 was unforgettable as he captured 6 wickets with a haul of 5 for 120, and Wally Hammond scored 217 runs as India lost the match.

Nissar had joined the Bengal North Western Railway as Assistant Traffic Superintendent. After the partition, he opted for Pakistan Western Railways. A BNW Railway official once remarked about Nissar. “India’s fastest bowler is working for India’s slowest railway.”

Mohammad Nissar was one of the founders of the Pakistan Cricket Board and worked as an administrator and a selector. He captained Pakistan’s Commander-in-Chief XI against Ceylon at Rawalpindi in 1950 where Miran Bakhsh made his debut. Nissar captured 3 for 31 in the match while Maqsood Ahmed got 6 for 45. Imtiaz Ahmed after keeping wickets in the match remarked, “Nissar was no longer fast but was still very accurate.”

Nissar remains an unforgettable legend in India but sadly he is hardly known in Pakistan. I first came across his name when I bought a board game of cricket at Delhi in 1955. Other great names I noticed there were Wazir Ali, Nazir Ali, Merchant, Bannerjee, Mushtaq Ali, Amarnath, Hammond, Bradman, Hutton, Verity, and Bowes.

In 2006 the Indian and Pakistan cricket boards started an annual match between the winners of the Ranji trophy and Quaid-e-Azam trophy. The event was named the Nissar Trophy but it now remains discontinued.

Nissar was married in 1942 and his Walima was held at the Nedous Hotel. His bride, a fair and beautiful Kashmiri lady stood tiny before him at 5′-3″. The union was described as a marriage between a fairy and a Djinn. Nissar was a cavalier in the true sense of the word and played “Cricket” in all his dealings. He last appeared for Pakistan Railways as a captain against Punjab in the Quaid-e-Azam trophy in December 1953 at the Aitchison College Lahore ground. Batting at number 8 he scored 27 runs but remained wicketless after bowling 7 overs and conceding 30 runs.

Sultan Mahmud, one of the last cricketers to have played against him appeared in that match and faced Nissar says that “Nissar was bowling with a very short run-up. Just 7 or 8 paces, his renowned pace had lost its fire but he was still very accurate and bowled with a nagging length. Sultan Mahmud also faced Jahangir Khan as a medium-pace bowler with much accuracy at Lahore Gymkhana ground.

Nissar died on March 11, 1963, and was buried at Miani Sahib graveyard, not far from the grave of his comrade and teammate Dr. Dilawar Hussain. At the time he was posted at Quetta and had come to Lahore to attend a railway conference and his younger brother’s marriage. He died on the Walima day in his Saloon at the Lahore Siding after a severe heart attack. He was only 52 years old. He had two daughters and a son. Although he was diabetic he had an enormous strength to bear pain without any complaint. Earlier one of the little toes of his foot had been amputated as a result of gangrene without any anesthesia.

Nissar was a right-arm fast bowler who took 5 wickets in an innings thrice in 6 Test matches. He took the first hat trick in first-class cricket in the sub-continent. He was a terrifying combination of speed and precision. He returned the most magnificent figures of 5 for 51 and 6 for 36 against the Australians in 1936-37 at the Lahore Gymkhana ground, Lawrence Gardens Lahore.

Upon learning of Nissar’s death, Lala Amarnath said, “Could it be true? I asked myself as I read in the morning papers on March 12, 1963, of the passing away at Lahore of a good old friend and comrade in arms Mohammad Nissar, only halfway through his life innings at the age of 53. I fervently hoped and prayed that history would repeat itself in the case of Nissar. For it was on a scorching May afternoon in 1935 that I heard of his ‘tragic death’ in the Quetta earthquake. The sports pages wore a black border and the editorial columns paid their last homage to the departed soul. A couple of days later came the unbelievable exciting news and a statement of gratitude from Nissar that the man who died was another one by the same name and it was his privilege of reading his own obituary and of knowing what the world thought of him.” The only other exception was, of course, Mark Twain who too knew what the world thought of him once he bowed out of the stage.

When Amarnath recalled this incident 20 years later in 1955 as the Manager of the Indian team to Pakistan, Nissar gave a big laugh and said, “No earthquake can shake me, you know.” Nissar was considered to be quicker off the pitch than in the air. His gentle nature always overruled his massive power and he would even decline his captain Syed Wazir Ali’s suggestion to bowl bumpers at the opposing team giving tough times. India’s first Test centurion Lala Amarnath owed a lot to Nissar for his career. He said that he could never forget Nissar’s help in 1933-34. A young Amarnath had come to Bombay for the all-India trials and had miserably failed in the first trial when he was sent to open the innings. Nissar realized that Amarnath had not been given a fair trial because his usual position was at number 3. He took it upon himself to convince the selectors and upon his recommendation, Amarnath was given another chance, and he scored 49 and 79 not out to be selected eventually. “Had he not helped me that day, perhaps I would not have played for India at all.”

In 2006 the Indian Cricket Board honored the great fast bowler Mohammad Nissar and presented a preserved piece of turf of Lord’s cricket ground to his son Waqar Nisar who upon my request donated the precious artifact for the Lahore Gymkhana Cricket Museum where it is now displayed with great pride and remains a priceless piece of history.