Even with the world’s best cricketing system in place, the Australians apparently struggle to digest the simple fact that excellence has little to do with age.

THE Australians are an amazing lot. Regardless of what the visiting Pakistanis feel while being there and what happens to them on the field of play, the Australians remain an amazing lot. They have one of the best, if not the best, cricketing systems in the world and their nurseries have done them much good, but their fascination with age is something that one finds amazing.

Even though there is no stated policy, the Australians don’t blood them young, preferring players to be in the mid-20s before they are considered good and mature enough for the national side. After the recent disaster against South Africa at home, there was much talk of an inside out change and all that blab la bla about time for giving youth a fair chance.

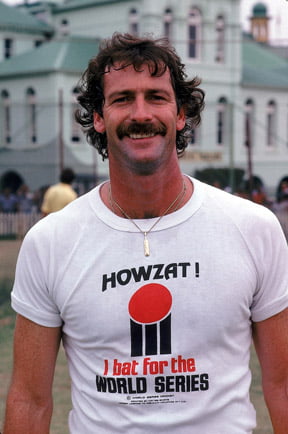

Deniss Lillee

As a result quote a few changes were made that were almost unprecedented in their cricketing history. It included Nick Maddinson at 24 years 360 days and Peter Handscomb at 25 years 233 days. Only Matt Renshaw could be called ‘young’ by global standards at 20 years 262 days. Among other changes were Jackson Bird, who had five Tests to his credit at 30 years 04 days, and Matthew Wade, who had 13 Tests at 28 years 355 days. With the exception of Renshaw, the others are new or relatively new, but not young by the standards of international sports.

A the other end of this somewhat inexplicable Australian fascination with age, they force their oldies out even when they are good enough to hold their place in the side. The names of Steve Waugh and Ricky Ponting pop up straight away, but there have been others like, say Adam Gilchrist and Michael Hussy in the recent past.

A little deeper into history, more than three decades ago, the famed Australian trio of Dennis Lillee, Rodney Marsh and Greg Chappell hung their cricketing boots at the end of the five-Test series against Pakistan in 1984. It took Australia more than a decade to fill the vacuum the three musketeers had left with their departure.

And, what a departure it was. Though Lillee had not publicly announced his retirement plan till the end of the match, Richie Benaud, the doyen of cricket commentators and analysts, was heard on air as saying it was the best he had seen Lillee bowl at any time of his hugely illustrious career. It was confirmation enough that the paceman who had frightened batsmen around the world for a long time was taking his last bow at the prime of his career. Not much different was the case of Chappell and Marsh.

If Lillee finished with eight wickets in the match, an economy rate of less than two runs and with a wicket on his last ball in Test cricket, Marsh ended up with six scalps behind the wicket, five of them in his last innings. Both of them finished, somewhat freakishly, with exactly the same number of victims against their names: 355.

As for Greg Chappell, he probably outdid both of them. With his massive 182 in his last innings, he became the first Australian ever to cross the 7,000-run mark, breaking the previous highest aggregate by an Australian of 6,996 which was in done by the legendary Don Bradman. The three catches he took during the game also meant a lot. With the catch in the first innings that sent Mudassar Nazar packing, he equaled Colin Cowdrey’s record of 120 victims in slips. And with the two in the second innings – those of Mohsin Khan and Salim Malik – he made the record all his very own.

The three – as do most Australian cricketers – were always known for their fighting spirit. The way they bowed out was clearly an indication that they were out to prove a point – perhaps to the selectors, the establishment and to the media who had all been gunning against them for some time on the plea that the ‘ageing’ trio was ‘blocking’ the path of some youngsters.

In his no-holds-barred autobiography, Menace, Lillee has chronicled the many ways in which he was pushed to the wall despite being the best bowler in terms of both averages and wickets on the Australian domestic circuit.

After Allan Border’s period of stablisation and Mark Taylor’s era of consolidation came Waugh’s tenure during which the word ‘invincible’ surfaced again as a description of the Australian supremacy in world cricket. It is strange that all three of them faced similar pressures at the end of their respective careers despite clearly having much cricket left in them.

Border, for instance, averaged 59 runs in his last Test against South Africa at Durban. Waugh averaged 60 in his last appearance which was against the visiting Indians at Sydney. Taylor had scored an unbeaten triple century just months before he threw in the towel at the end of the successful Ashes series at Sydney.

The momentum generated by Waugh with his shrewd captaincy did last for a while during which Ricky Ponting looked good, but with Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne moving out and with the likes of Justin Langer, Gilchrist and Mathew Hayden facing the same pressure as did their predecessors, the Australians suddenly had nothing to fall back on and nobody to look up to.

And, them as fate would have it, Ponting faced the same pressure, but, this time at the wrong end of it, because this time he had ‘aged’ and was ‘blocking’ the way of Michael Clarke. This is really an amazing aspect of Australian cricket.

They have avoided falling to the sordid depths to which teams like, say, the West Indies and Pakistan do in times of crises because they have a decent system in place while the others do not have anything in the name of a system. As such, it is more likely that Steven Smith, and whoever follows him, will repeat the Border act of gathering human resources and trying to be competitive over a period of time before they have the nucleus ready for a side that may reclaim the lost ground. That it will be good for cricket is something that goes without saying.

The most amazing aspect of the whole episode is that even with an elaborate system in place, the Australians have struggled to digest the simple fact that excellence has very little to do with age. The raw talent has its place and so does the old fox. In fact, there are individuals – and they are there in all walks of life – whose talent matures either too early or a bit too late than the average. By focusing on a pre-determined average age, one is depriving oneself of decent human resources. The human frailty, indeed, has the potential to ruin even the best of systems. Amazing, isn’t it?