Was ever a cricketer more loved than Johnny Briggs?

There may, I suppose, have been a few, but at his funeral in 1902, no less than 25,000 people turned out to honour a man who may be counted one of the first great left-arm spinners, and who filled a career of more than 20 years with cleverly taken wickets, carelessly acquired runs, and numerous quotes from Shakespeare.

Despite his tragic early demise at 39, his achievement was great. He was the first man to take 100 Test wickets, and he held the title of taker of most test wickets in 1895 and then from 1898-1904.

Even now he is the taker of most wickets ever for Lancashire except for Brian Statham. With more than 2,000 wickets and 14,000 runs, having scored ten first class centuries, including one in his second test match against Australia, he was also the greatest allrounder ever produced by Lancashire.

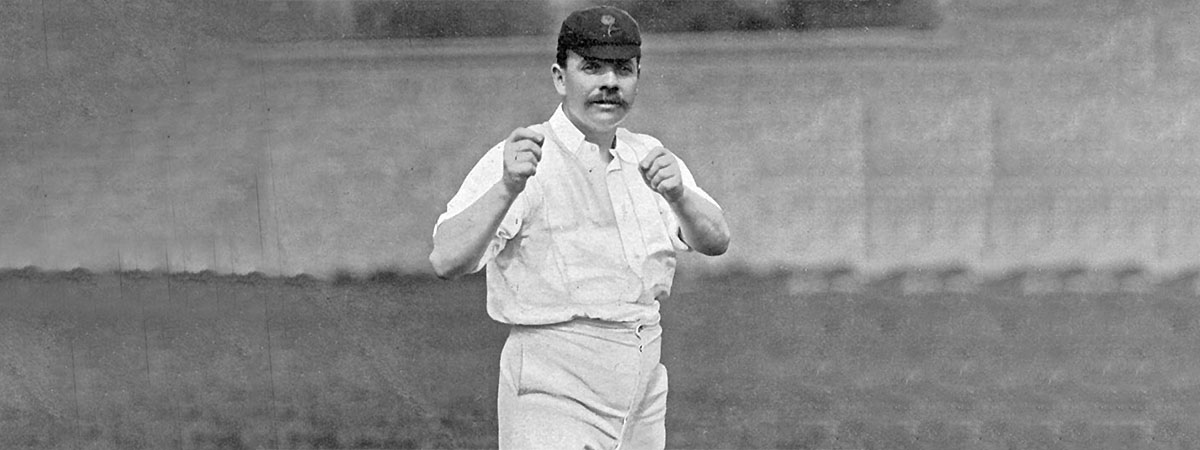

Johnny Briggs was born in Nottinghamshire in 1862, the very year in which overarm bowling was finally legalised. He was short, chubby, and, having been taken onto the professional staff at, astonishingly, 13, he made his debut for Lancashire in 1879 at the age of 16 – incredibly young for a spin bowler. At that age he was actually known more for his batting and fielding than for his bowling. His nickname was, naturally, ‘Boy’, and that stuck to him. Indeed, his countenance continued to be quite boyish despite a thick, handlebar moustache.

He had large, friendly eyes and, unlike (it must be said) many of his left-arm spinning.

brethren, was a sunny character, greatly appreciated by crowds both at county and test level, including in Australia. Whether Johnny bowled or batted or fielded, something was likely to happen, one way or another. Apart from being a great bowler and an entertaining batsman he was also a superb fielder, especially in his youth. Within five years of his county debut he suddenly emerged as a mature bowler, and this was, oddly enough, shortly after he made his debut for England in 1884; and he was on his way to becoming a great bowler, and a rapidly improving batsman too.

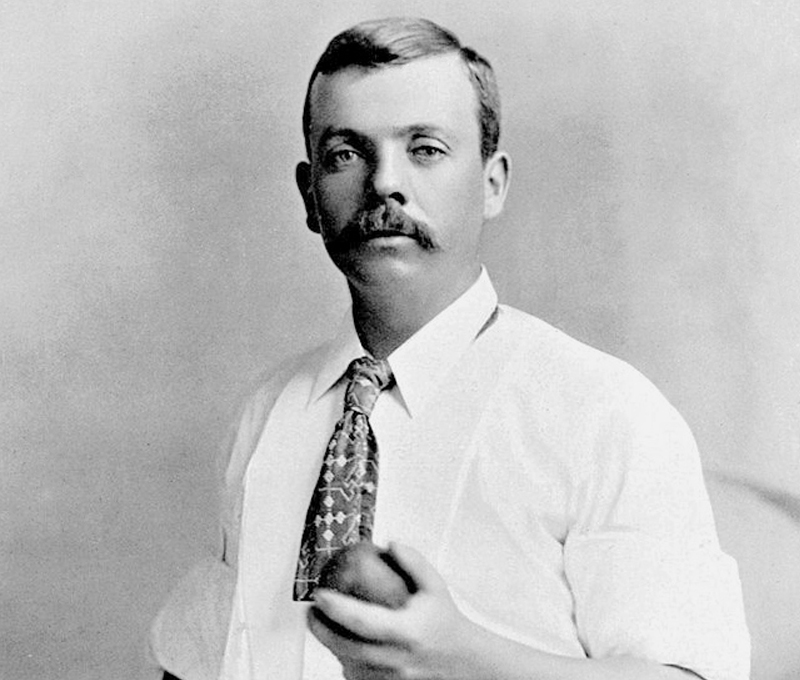

It is an interesting question, from where did Johnny acquire his skills at such an early age? After all, there was at the time little in the way of a slow-left-arm bowling tradition, even in the North of England, which produced three great slow-left-armers, but all at more or less the same time: in order of emergence, Ted Peate, Bobby Peel, and Johnny Briggs.

Lancashire had, however, another left-arm spinner, George Nash, who was twelve years older than Briggs, and Johnny may have learned from him. But Nash made his debut for Lancashire in the same year as Briggs, despite being much older, and they were essentially in competition for the place. This competition was easily won by the younger man, although Nash was still playing for Lancashire occasionally 16 years later, and must have been a good bowler, taking altogether 232 wickets at 12 apiece. But he only played 53 first-class games, and unlike Briggs, was not an all-rounder – that may have made all the difference in terms of selection. If Nash did influence Johnny Briggs, it seems Johnny must have quickly grown beyond what he could have learned.

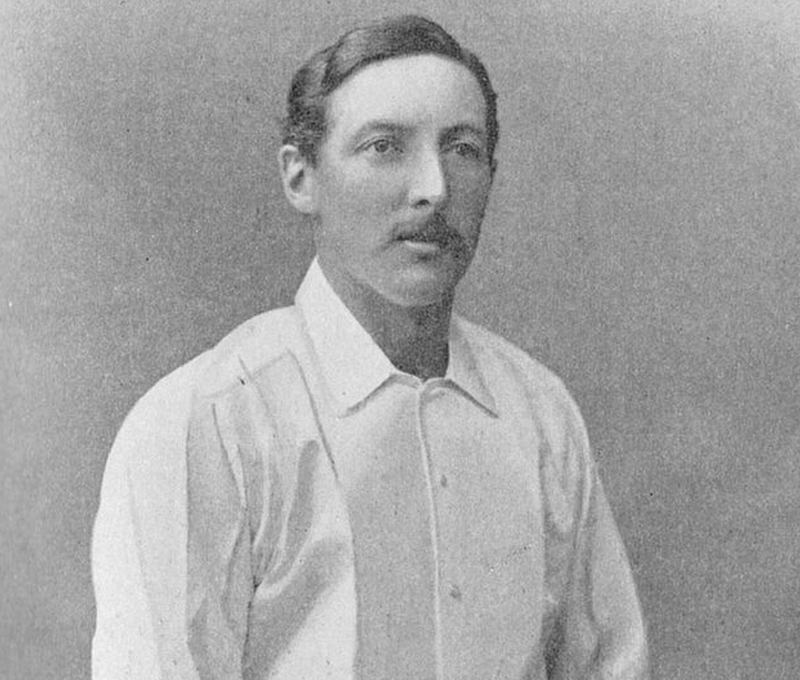

Briggs first played for England before he was even well known as a bowler. Indeed, his selection is a bit of a mystery. He toured Australia with Arthur Shaw’s team under Shrewsbury’s captaincy in 1884/5, and although he barely bowled in the five-match test series, he batted at number 7 or 8 and scored a brilliant 121 in 150 minutes in his second test at Melbourne. Peel, on the other hand, who was ultimately his main rival, bowled an extraordinarily large number of overs, taking 21 wickets.

Taking 79 wickets for Lancashire at 10 apiece in 1885, Briggs first came to national attention as a bowler in 1886. He was selected for the first test against Australia at Manchester, but did not bowl in that match. England’s premier spinner was Yorkshire’s Ted Peate, who had a poor game.

With Peel seemingly out of favour with the selectors, in the Lord’s test Briggs effectively replaced Peate on a permanent basis. He was brought on with the match evenly balanced after England, boosted by 164 from Shrewsbury, had scored 353. Briggs was immediately successful, taking 5 for 29 and 6 for 45 as Australia were forced to follow on, collapsing twice, and losing by an innings and 106 runs. Scoring was very slow and Briggs must have been virtually impossible to score off, bowling 72 (four-ball) overs for 74 runs.

In the third test, Briggs again had a good match, scoring 53 in a stand of 90 with Read in England’s innings, taking 3 for 28 in Australia’s collapse to 65 all out, then 3 for 30 in the second innings, bowling with Lohmann who took 12 wickets as England crushed Australia by an innings and 207 runs.

At Sydney a few months later, on what was already Briggs’ second tour of Australia, he played in an astonishing test match in which England, bundled out for 45 in their first innings, won by 13 runs as Australia were bowled out by Billy Barnes. Briggs did little with the ball but top scored with a crucial, match-winning (as it turned out) 33 going in at number eight in England’s second innings.

In the second Test, also at Sydney and also low-scoring, Briggs’ 3 for 30 in the second innings helped England to another win by 71 runs, in spite of their extreme difficulty with the fast bowling of Ferris and Turner. By this time Briggs was an integral part of the England set-up, and was an automatic selection in spite of having to compete with another great left-arm spinner, Yorkshire’s Bobby Peel, who had made his debut earlier. Peel was soon back in contention, taking nine wickets at Sydney against Australia in 1888, while Briggs was not used.

They often played in the same team, as at Sydney in 1894, which witnessed one of the most amazing reversals in test history, a match in which both spinners played an important part. Australia hoisted a huge first innings score of 583, courtesy of a double hundred by Syd Gregory and 161 from George Giffen. When Briggs came in to bat, England were on the edge at 211 for 6, but a lively 57 from Briggs helped them to 325.

Nonetheless they had to follow on. Again England were on the edge at 296 for 6 when Briggs came in to bat, and his useful 42 helped them to 437. Australia needed 177 to win, and were going well at 130 for 2 when overnight rain changed the conditions in England’s favour. Peel (6 for 67) and Briggs (3 for 30) went through Australia like a knife through butter to give England victory by just 10 runs. Briggs’ two contributions with the bat and his second innings wickets in support of Peel constituted, again, a match-winning performance.

Over several seasons and tours, Briggs and Peel alternated in the England side. Both were classified as all-rounders, and when one failed to fire, the other invariably did. When they bowled together they were formidable. But selection was a lottery in those days, home test teams in England being selected by the club hosting the test match. So little need be attached to the several occasions when Briggs was not included. Nonetheless, Briggs toured Australia a record six times, and was as well known and as popular on the hill at Sydney as he was at Old Trafford and around England. In 1892 at Sydney, Briggs took the wickets of Giffen, Blackham and Calloway in successive balls.

This was, oddly, the first test hat trick not taken at Melbourne, and the first test hat trick by a bowler on the losing side (by 72 runs), a disappointment probably more than equalled by Bobby Abel carrying his bat in England’s second innings for 132 not out, Briggs making the second highest score of 28.

Briggs’ best test performance was on England’s first tour of South Africa in the second test at Cape Town in 1889. The South Africans were demolished by Briggs, all out for 47 and 43. Briggs was unplayable, with the astonishing match figures of 15 wickets for 28 runs, 14 of which were bowled, which is astonishing for a left-arm spinner. Other notable performances were 6 for 49 against Australia at Adelaide in 1892, and 5 for 34 against Australia at The Oval in 1893.

As a batsman, Briggs was talented but mercurial. He was good enough to open the batting for England on three occasions, including with Archie McLaren, but he never approached his top test score of 121 in his second test, and had a tendency to be out for nought, except when adding some breezy and useful runs at number eight. He was criticised for showing lack of application, but the 1880s and 1890s were very slow-scoring times. Crowds no doubt thought Briggs a breath of fresh air with the bat.

Briggs’ performances for Lancashire were many and legendary. His best season with the ball was 1888, when he took 160 at 10.49 each. His spin, loop, and guile on uncovered pitches made him a deadly proposition. He was also not the only professional to cross swords with Yorkshire’s mighty leader, Lord Hawke.

It happened in this manner. Benefit games were vital for the post-cricket security of professional players, and in 1894 Johnny Briggs, very understandably, nominated the Roses clash with Yorkshire as his benefit match. To guard against bad weather, not unknown at Old Trafford, Lancashire had prepared two wickets for the game, one of which had been covered. Following rain, Lord Hawke refused to play on the covered wicket, and as a result the game ended early on the second day. Briggs, well out of pocket, was distraught. Many thought the aristocrat’s behaviour was extremely shabby.

In one of those inexplicable reversals that seem to overtake cricketers, extreme misfortune overtook Johnny Briggs mercilessly and suddenly in 1899. First, he was hit in the ribs while fielding in a county match and collapsed. This blow seems to have had continuing health consequences; it was not realised until later that a rib had punctured his heart.

Then, late in the same season during the Leeds test match against Australia, he had an epileptic seizure so severe that his season was ended. He was soon taken to the mental asylum at Cheadle, where, after a good season in 1900, he was readmitted in 1901 and died in 1902. It is said that he would surprise inmates and visitors in the corridor with sudden cries of ‘Owzat!’, as though reliving his life in cricket. It seems likely that Johnny had suffered from epilepsy earlier. The condition is not of course inconsistent with a full life of action, as Tony Grieg was to prove later, and Julius Caesar had done long before.

One thing about Johnny Briggs’ colourful life is unclear. His gift of quoting lengthy extracts from Shakespeare suggests he was among the most erudite of cricketers, which is odd for a man of little formal education.

Taken on by Lancashire at 13 and spending his life as a professional cricketer, where did Briggs learn all those quotes from Shakespeare, which would no doubt have amused the non-striker, the umpire and the mid-off fieldsman as he ran in to bowl? It is not recorded whether any batsman was upended by some Shakespearean curse or denunciation.

Perhaps he learned Shakespeare in school in his early years, or by self-study during the winter months. At any rate a grateful Lancashire crowd mourned his early passing with genuine sadness, and he was indeed one of the game’s much-loved characters.