Cricket is a team game. As such a cricket match is played between two sides comprising eleven players each. But if both sides want to play a match with more or less than eleven players, they can still play a legitimate match. If, however they chose to play with more than eleven players each side, only eleven players would be allowed to field at a time and the remaining two players would stay outside the field of play. But all the thirteen players are entitled to bat and bowl normally.

The Laws of Cricket do not say which matches should have eleven players-a-side and which more or less than eleven. Is it due to an anomaly in the Laws that the number of players is not fixed or has it anything to do with the status of a match? In fact neither is the case.

By design, the Laws of Cricket are meant to apply to all players alike irrespective of their ages, genders or skills and are capable of dealing with any conceivable situation, fairly. For instance if the number of players were fixed at eleven-a-side, all those not being able to raise eleven players for themselves won’t be able to play a cricket match.

But the common observation is that in almost every cricket match the competing sides comprise eleven players each. It has nothing to do with the status of a match but appears as a loose bifurcation between competitive cricket and social cricket. But then there are instances where 12-a-side matches have been highly competitive and 11-a-side completely social.

On the other hand those who want all of their thirteen players, for example, to play won’t be able to play a cricket match. Thus cricket would be restricted. It’s said, and truly so that ‘cricket owes much of its enjoyment and appeal’ to the Laws of Cricket.

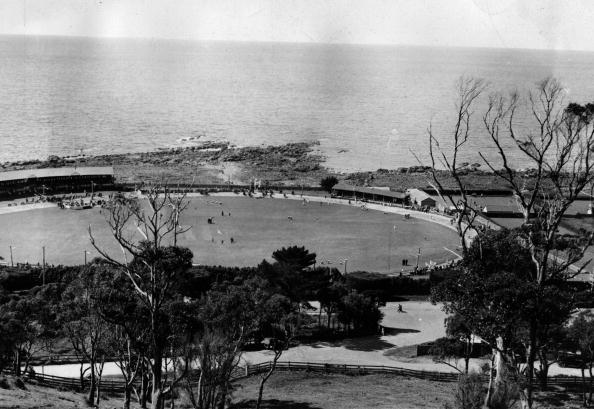

Like the number of players on each side not being fixed, the duration of a match, the number of innings in a match or the size of a cricket ground is not fixed either. A cricket match can be played properly according to the convenience of availability – availability of players, time and size of field of play.

But the common observation is that in almost every cricket match the competing sides comprise eleven players each. It has nothing to do with the status of a match but appears as a loose bifurcation between competitive cricket and social cricket. But then there are instances where 12-a-side matches have been highly competitive and 11-a-side completely social.

Although the number of players in a side or the duration of a cricket match had not been of much interest to the players or the followers of the game for a long time, yet it certainly had been confusing for historians who wanted to keep statistical records of the game but could not do so in the absence of an authentic classification of competitions. It was therefore in the fitness of things that at least First Class Cricket was separated from the rest of it ending the confusion as to which matches could be regarded as First Class.

But the common observation is that in almost every cricket match the competing sides comprise eleven players each. It has nothing to do with the status of a match but appears as a loose bifurcation between competitive cricket and social cricket. But then there are instances where 12-a-side matches have been highly competitive and 11-a-side completely social.

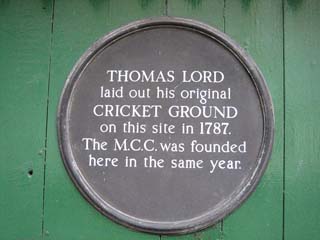

Accordingly, in 1947 it was decided by the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), the custodians of the Laws of Cricket that all First-Class matches would be judged by the following criteria. No decision was however taken on the matches that had been played prior to 1947. They were to retain their original status.

Criteria for awarding First-Class status to a Cricket match

Duration of a match

The first code of the Laws of Cricket was introduced in 1744. For the next over two hundred years the duration of Cricket matches ranged from a few hours to till-finish games. In the absence of any set rules for judging the status of a cricket match, during this period 2-day matches had been designated as first class at the same time 4-day competitions were not regarded as First-Class.

It was therefore decided to fix a minimum duration of a cricket match before it could be classified as First-Class. So the first condition placed for a First-Class match was that it should not be of less than 3 full days’ duration, with no limit on the maximum number of days over which a First-Class match can be played.

Number of players in each side

Fixing the minimum number of days for a First-Class match alone was not enough. Something more was needed, otherwise any two sides could, after playing a 3-day match between themselves, claim First-Class status. It was therefore decided that every First Class Cricket match will have eleven players-a-side: neither more nor less.

Before that there was no limit on the number of players on each side, we had seen 12-a-side matches being classified as First-Class. Now a deviation from the fixed number of eleven players may not allow any match to be considered as First-Class.

Recognition of the Governing Body

Complying with the above requirements, if two sides with eleven players each play a 4-day match and on their own designate it as a First-Class match, can this match be considered as First- Class? The answer is no – because it lacks the concerned authority’s approval. Authority means any undisputed Governing Body running affairs of Cricket in the country.

Putting together the three requirements without which no match can attain the First Class status, we have a formidable yet instant formula to judge the First-Class status of a Cricket match. The formula also simplifies the classification of Cricket as First-Class Cricket and Non-First Class Cricket.

It may be interesting to note that the international competitions like ODI and Twenty-20, are not First Class tournaments. As such any matches under this arrangement, although played between countries like Test Matches are not regarded as First Class – because the duration of matches in these tournament is not 3 days or more.

Mahboob Shah, before becoming an umpire, he played in 14 first-class matches between 1954/55 and 1960/61. He umpired 28 Test matches and 32 ODIs between March 1975 and March 1997. In 1994, he and Khizer Hayat were the two Pakistani representatives on the first international panel of umpires. He umpired in the 1987 Cricket World Cup final between Australia and England at Eden Gardens, Calcutta, on 8 November 1987.