It is the unforgettable moments in one’s life that make life worthwhile. Remembering one’s first love or taking the first wicket or the first day at school all leave an undeniable mark for the rest of our lives. Memories are like a rainbow which consist of a glorious and colorful tapestry of the thoughts in our minds. Cricket remains the only game in the world that is most talked about, written about, and remembered.

A. H. Kardar, Karachi, December 1954:

|

Meeting Skipper Kardar for the first time in the main hall of the old building of the Karachi Airport was the turning point. Pakistan cricket team had recently registered its great victory by defeating England at The Oval and Kardar was at the zenith of his fame and popularity. Kardar, tall, slim, and fair-complexioned stood there towering over everyone present. I felt overawed. He stood erect with his stiff neck at an angle and pleasantly shook hands with us. I was indoctrinated into cricket at that moment. I next saw Kardar, leading the Pakistan team, in the Lahore Test against India. I noticed him from the dining hall where the first cricket museum of Pakistan now stands, he was in the dressing room of the home team in his shirt and underwear. He saw me and grandly motioned that I approach him. Maqsood Ahmed “Merry Max” stood next to him smoking. Both graciously signed their autographs in the souvenir. Maqsood Ahmed became my cricket coach and friend at the cricket camp at Karachi in 1962. Kardar and I remained in touch through correspondence. C. L. R. James writing in his greatest book on cricket, “Beyond a Boundary”, describes the panther-like gait of Kardar when he would lead his men out on the field. I saw him lead in the Test matches against India, New Zealand, and the MCC ‘A’ at the Gymkhana ground Lawrence Garden. I was present when he emerged from the Lahore Gymkhana pavilion and walked out to bat in the trial match in a last failed attempt to regain his captaincy of the team that was to tour India under Fazal in 1960-61. Still erect, with his stiff neck at an angle like always, he walked into the sunset of his career.

M. K. Mantri, Lahore, January 1955:

|

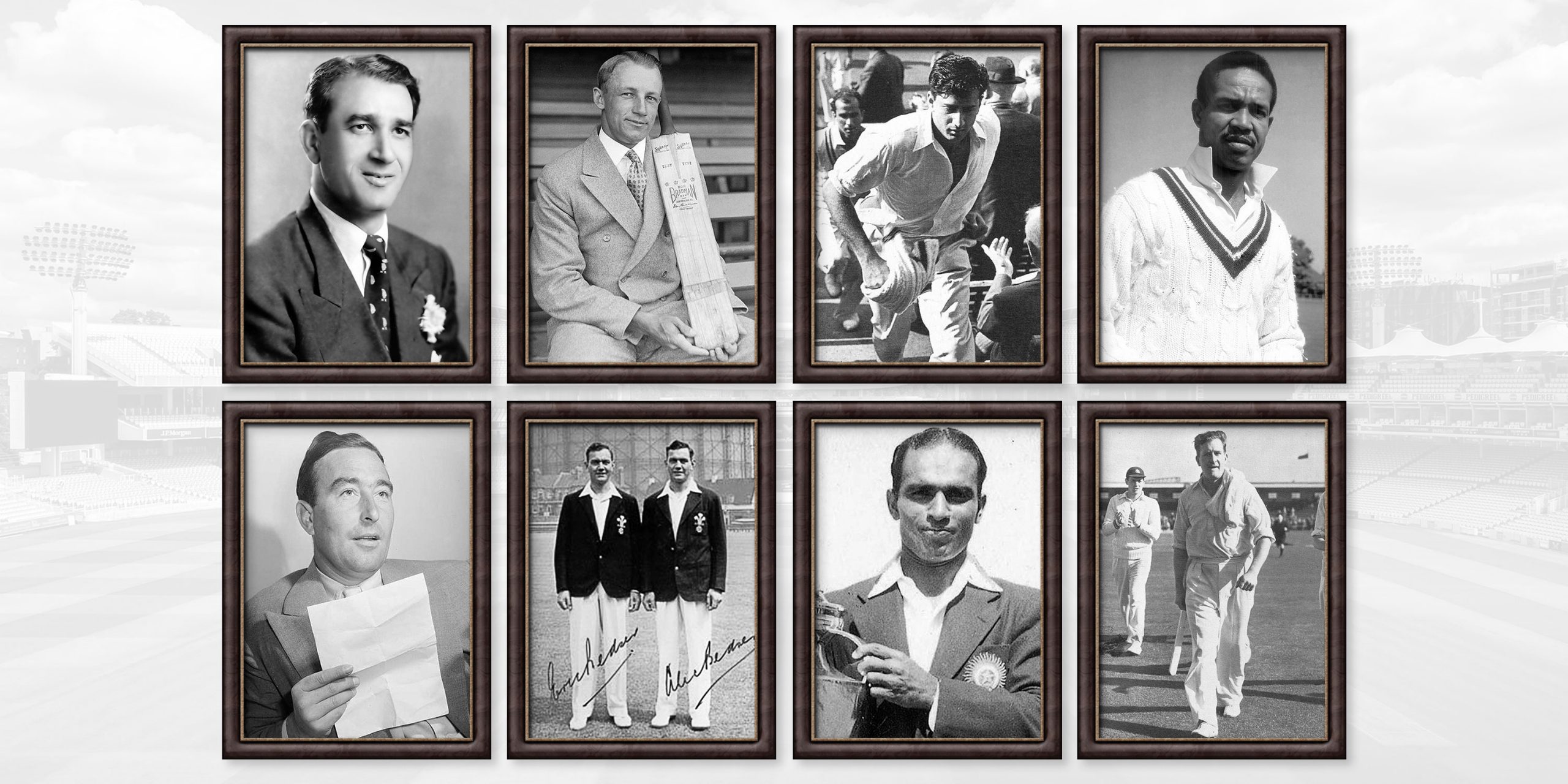

Some members of the Indian cricket team M. K. Mantri, Prakash Bhandari, and a very young Chandu Borde sitting on the reclining chairs outside the Gymkhana pavilion during the Lahore Test. As I went to them for their autographs, one of them, M. K. Mantri asked me if I would become his pen friend? Although surprised, I said yes. We exchanged letters for the next 50 years. From pen friends, we became family friends. The friendship lasted till 2014 when he passed away. He visited our home in 1961 as captain of the Associated Cement Company touring team to Pakistan. I always called on him whenever I was in Bombay. He was a gentleman of the old world and possessed exemplary character. His record of 9 dismissals (4 Ct/5St) on his debut in a Ranji Trophy match played at the Lahore Gymkhana ground Lawrence Garden in 1941-42 between Bombay and Northern India stood for the next 18 years. He gave me a historic signed picture of the Lord’s Test between India and England of 1952 where he is taking a catch of Hutton off Hazare for 150. That Test match is known as Mankad’s Test because he scored 72 in the first innings and was bowled by Jim Laker for 184 in the second innings. He also took 5 wickets for 196 runs in England’s first innings.

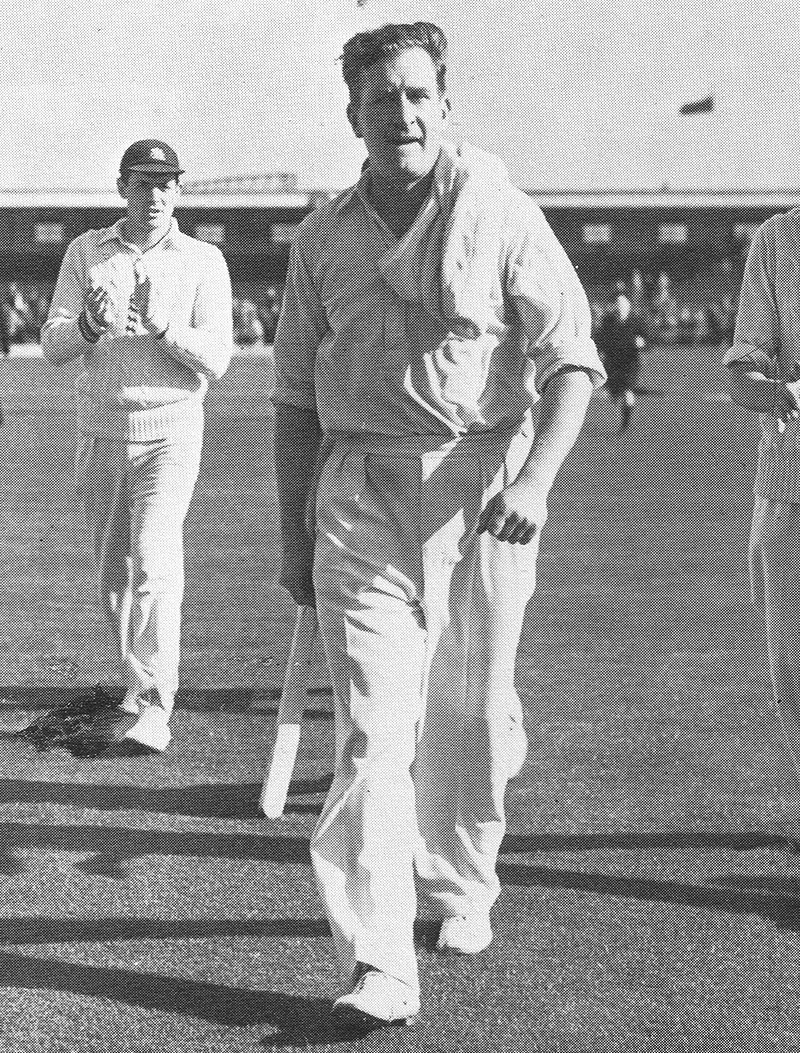

Fazal Mahmood, Lahore, January 1955:

|

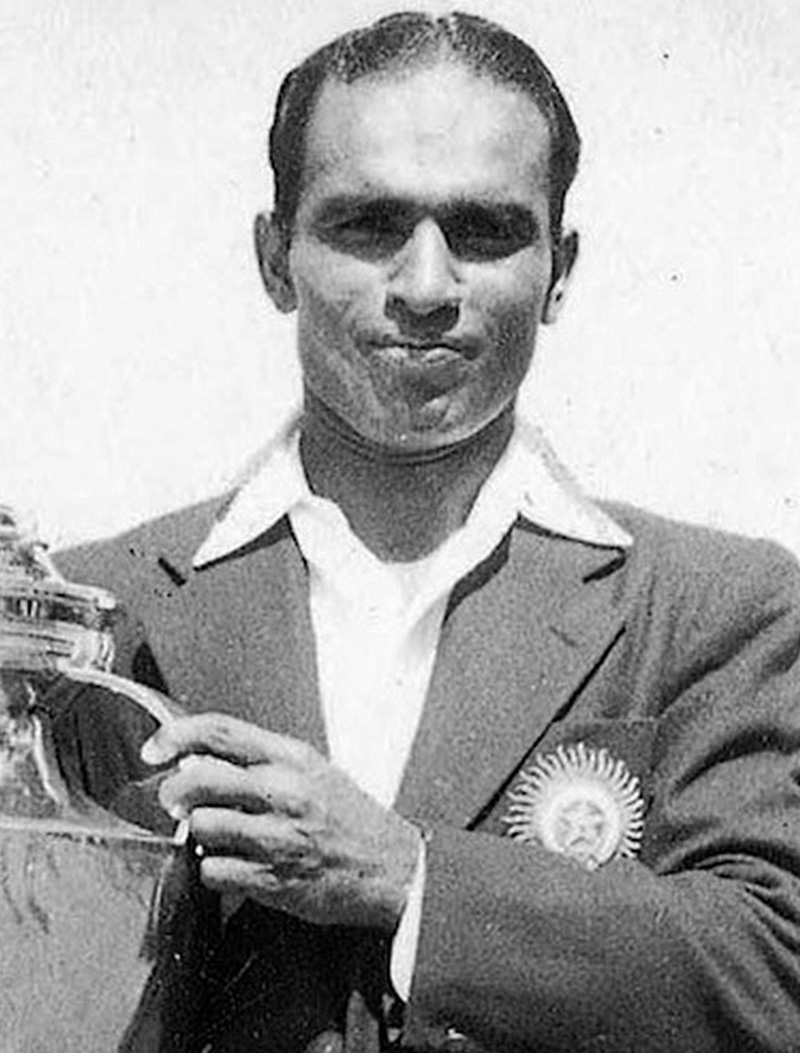

I had only read about the Greek gods till I saw Fazal Mahmood for the first time during the Lahore Test against India. His grey-blue eyes were extremely attractive and magnetic. He stood outside the pavilion near the boundary rope looking resplendent in Pakistan’s green blazer sporting the eagle, star, and crescent badge. He was at the height of his career. He had recently won the title of The Oval hero by taking 12 wickets for 99 against England. Fazal never got over The Oval Test. Even now his spirit may surely be hovering at The Oval. The Oval Test even after 66 years is still fresh in the minds of cricket lovers of Pakistan. During a visit to The Oval ground in 1987, upon my request to see the famous balcony where Fazal once stood and waived at the crowd after the historic victory in 1954, Kate Hampsall, from the staff, took me to the exact spot. There has never been a more handsome cricketer than him anywhere in the world. Upon meeting him at the Horse & Cattle Show in 1981, my wife Becky, remarked that he ought to be in the movies. My daughter, Ambereen, who sat with General Zia-ul-Haq at the Show said, “I thought he was an Englishman who could speak in Punjabi with the President.” I remained an ardent admirer forever. Soon after seeing him in the Lahore Test of 1955, I discovered he was posted as the Deputy Superintendent of Police at the Police Headquarter on Empress Road. I would call him several times every day as he always answered the phone himself until one day, he invited me to come to his office. I went there with a friend Khalid Mustafa and younger sister Yasmin, all school going kids. He treated us with ice cream. In 1959 when he was leading Pakistan against the West Indies at Lahore, I saw him on the veranda of the Gymkhana pavilion. He was in his cricket kit, wearing Hawaii slippers, so I requested him for a photograph. Taking a puff at his cigarette he stepped near the wooden arch of the pavilion. I noticed the yellow fingers of his right hand from smoking cigarettes. He broke my trance saying “Make it snappy boy!” We met again in December 2001 during the annual festival cricket match of the Universal Club at the Aitchison College. From then on till his death in 2005, we remained close friends. He even bowled the last ball of his life to me at the center wicket of Lahore Gymkhana while Imtiaz Ahmed stood behind as a wicket-keeper. I contributed nearly 40 pictures to his autobiography From Dusk to Dawn. His generous hospitality, affection, and charm remain unforgettable.

Sir Garfield Sobers, Manchester, August 1972:

|

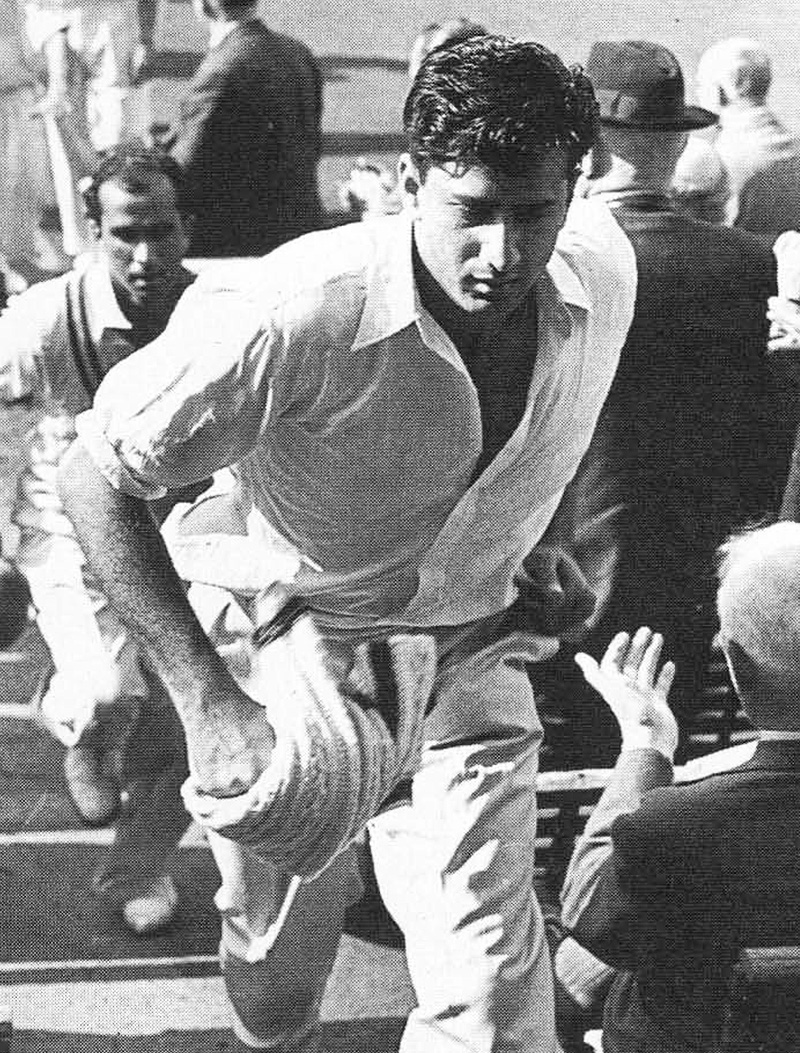

I saw Garry Sobers, the first time, at the Lahore Gymkhana cricket ground during the 1959 Test. He was then the world champion who had scored 365 runs, but his demeanor was full of arrogance. He had his shirt collar pulled up as a sign of superiority complex. In his heydays, Sir Garfield Sobers would not sign autographs easily and would refuse in a rude and harsh manner. In those days, cricketers who thought themselves to be extraordinary would turn up their shirt collars as a sign of disdain and arrogance. From the Pakistan side, Saeed Ahmed and his brother Younis Ahmed had their collars up. After the day’s play, my younger sister and I ventured out to Faletti’s hotel where the West Indies team was staying on the upper floor of the left-hand block near the entrance gate. The block has now been demolished. My younger sister was a chirpy little 10 years old kid, went up and got the autographs of all the players including that of Sobers. When our mother came to pick us up, she hit the roof when she learned that I had sent my sister to the player’s room all by herself. One unforgettable shot of Sobers in his remarkable innings of 72 runs in the Lahore Test is still etched in the mind. He was batting at the pavilion end when he blasted a ball from Mahmood Hussain with a wristy late cut. Before you could see, the ball had sped and reached the boundary tearing away through the grass. I also saw Leg Spinner S. F. Rahman there, who deserved to play the Test, but was included only as a 12th man. In the previous match, he had taken the top 5 wickets of the West Indies line up including that of Garfield Sobers at Peshawar for the President’s XI. He had also trapped Sobers lbw in the West Indies in 1957-58 but the umpire did not give him out. Instead, Mushtaq Mohammed made his debut in the Test and became one of the victims of the hat trick of Wesley Hall. Garry Sobers remained most unhappy on that tour of Pakistan. He was furious for being out lbw thrice to Fazal Mahmood out of his five innings. He has written about his disgust in all of his books. He became Fazal’s 100th Test wicket when he got out lbw for 14 in the 2nd innings of the first Test at Karachi. Earlier he was declared out lbw to Fazal for 0 in the first innings. Sobers went mad and told the manager of his team Berkeley Gaskin that he will not play in Pakistan. He packed his bags to return home. After much persuasion, he stayed, but was again given out lbw to Fazal for 29 in the first innings of the 2nd Test at Dacca. Collie Smith, generally a jolly fellow, batting at the other end, became agitated and yelled at Fazal. Sobers was well out of the crease when the ball hit his pads. Even Wicket Keeper Imtiaz Ahmed and Ijaz Butt at first slip knew that Sobers was not out. They both told Fazal loudly in Punjabi to call Sobers back, but Fazal retorted, “Let him go. He’s recorded out in the scorebooks.” Sobers scored 45 runs in the second innings, but was quite wound up by the time he arrived at Lahore for the last Test. In 1972, I came across Sobers at Peter Stringfellow’s world-famous nightclub, The Millionaire Club, at Manchester. Sobers was standing in a corner near the bar having a drink and eyeing all the pretty girls. The Millionaire Club was the first discotheque that revolutionized and changed the Club scene in the world. The most beautiful girls from all over would flock to this club. Peter Stringfellow, was a close friend of Princess Margaret and with flowing long hair, drove a convertible Cadillac and was a celebrity disc jockey of his Club. He even came to a party at my house in Cheshire and took charge of music to make it a memorable occasion. Just out of courtesy I greeted Sobers, who in turn gave me a sloshed icy look and just stared at me. When I offered him a drink, I was shocked that he rudely hissed at me and told me to just get lost. I had never expected such disgusting behavior from a cricketer of his standing. Perhaps he was still smarting from those lbw decisions in Pakistan.

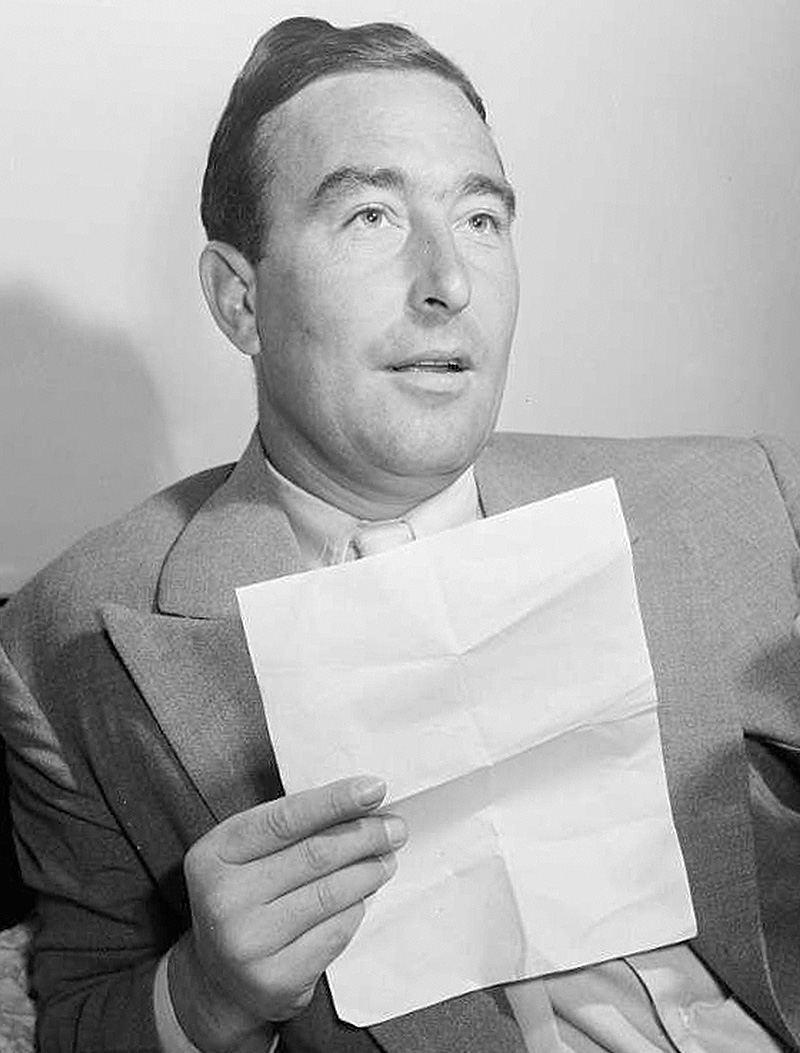

J. C. Laker, London, February 1980:

|

I was briefly in London, before returning to the United States and came across the phone number of the great Jim Laker by chance. I dialed the number and immediately recognized his heavy voice when he answered the phone himself. It was a great moment for me to be speaking to the man who held the unbeatable world record of taking 19 wickets for 90 runs in Test cricket. Much before that, he had achieved astonishing figures in the Test Trial at Bradford in May 1950 when playing for England against the Rest of England he bowled 8 wickets for 2 runs. Before the Test at Old Trafford in 1956, Surrey had beaten the Australians at The Oval by 10 wickets. Jim Laker took all 10 wickets in the first innings for 88 runs. Tony Lock took 7 wickets for 49 in the 2nd innings to seal the victory. Laker’s demeanor was unforgettable. He was polite, unassuming, dignified, and down to earth. After exchanging pleasantries, I asked him for an autographed photo. He said he would be delighted to do the needful, but the problem was that I was leaving the next day and there was not enough time to get his picture. When I brought my dilemma to his attention, he said, ” In that case, please give me your address in the States, I will send you the picture by post.” I gave him the address but, in my heart, I was not sure if he would take all the trouble of posting his signed picture to a complete stranger. Nevertheless, about two weeks later, to my immense joy and surprise, I opened an envelope from England to receive the much-desired inscribed photograph.

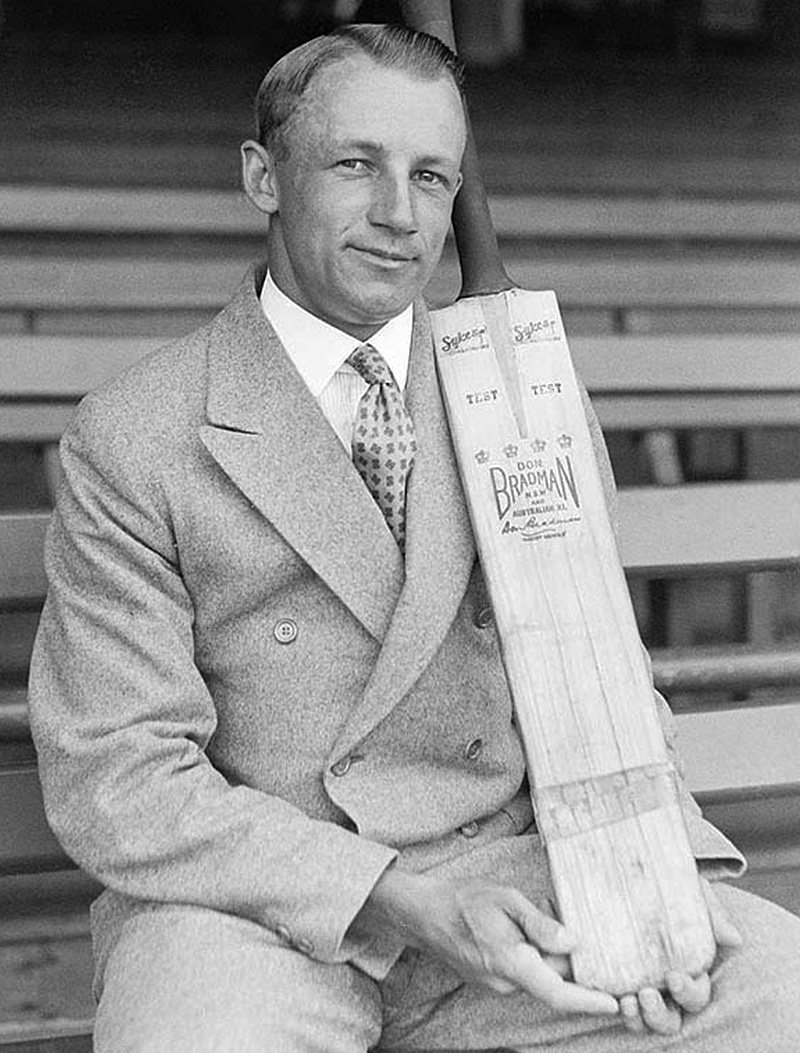

Sir Donald Bradman, 1984:

|

Col. Keith Howard the Defense Attache at the Australian Embassy at Islamabad and his delightful wife Joan had often stayed with us at Sahiwal and had gone with us on wild boar hunting at the lands of my friend late Raja Shahid Saeed. Col. Howard had known Sir Don Bradman personally. So, when he was returning to Australia, he asked me if I needed anything from there? I requested a signed photograph of Bradman. Several weeks later Keith rang me from Australia and said he had sent a signed book of Sir Don through the Australian Embassy but it never reached me. However soon I received in mail a beautifully inscribed autograph of Sir Don, the greatest batsman of all time. When he was bowled for 0 by Eric Hollies in his last appearance in 1948, it became the biggest news. Arthur Morris, who was batting at the other end with a century, wry-fully remarked, “The world forgot my century but got excited about Don’s 0.” Keith had also enclosed a letter of Sir Don written to him which read ” I appreciate your friend’s request for my signed photograph but do you realize how much it can cost me printing photographs for such requests from strangers?”

D. C. S. Compton, London, September 1986:

|

One late afternoon as I walked in Baker Street London on my way to Oxford Street, I noticed a familiar face crossed the street and started to walk ahead of me. My heart missed a beat when I realized it was none other than the great England cricketer and footballer, Denis Compton, the hero of the summer of 1947. He was as handsome as when he appeared in Brylcreem advertisements but had put on quite some weight. I kept on walking behind him thinking that he may not like being accosted in the street. Soon he reached his office at Ryman Stationery at Wardour Street. I followed him in. The girl at the reception asked me whom did I wish to see? I asked her if the gentleman who had just entered was Mr. Denis Compton and if I could meet him? She smiled and spoke to Denis Compton on the intercom, “Someone’s here to meet you about cricket, Denis.” Within about a minute I saw the great man coming down the steps with a very pleasant smile. He warmly greeted me and shook hands and asked where I was from? Upon hearing that I was from Pakistan, he exclaimed, “Oh, Faazal’s Pakistan!.” He was referring to Pakistan’s lion-hearted bowler Fazal Mahmood. He said he had just returned from his regular lunch haunt at the Cricketer’s Club of London. He said, “You know, Faazal was a great bowler who bowled me first ball for a duck at Lord’s in the first Test and then got me caught twice by Imtiaz off his bowling for 53 and 29 at The Oval in 1954. My performance of 53 in the Test against him was very difficult but I consider it one of my best innings where I was at least dropped twice of Faazal’s bowling”. He talked of the time when he played in Ranji Trophy in India and saw Fazal there the first time. Denis Compton further reminiscences when on his way to Australia the airplane had to land at Karachi due to engine trouble where he was met by Hanif Mohammed, Wazir Mohammed, Mushtaq Mohammed, and Sadiq Mohammed. He was graciously feted by Kafiluddin the iconic PWD officer who built the National Stadium at Karachi in record time in 1955 for the Test against India where Pakistan’s Alimuddin became the first centurion. Compton talked about his highest Test innings of 278 runs at Trent Bridge against Pakistan in 1954. He said he just got tired of batting and gifted away his wicket to the young leg spinner Khalid Hassan who had toiled hard. Compton said, “I felt a bit sorry for the young bowler and I was getting tired. So, when he bowled, I went forward and lifted the bat out of the way of the ball to just let it go through to the wickets and did not offer a stroke.” I then requested him for an autograph. “With great pleasure. Who should it be for?” He asked. “For my daughter”, I replied. It was yet another unforgettable moment among the greats.

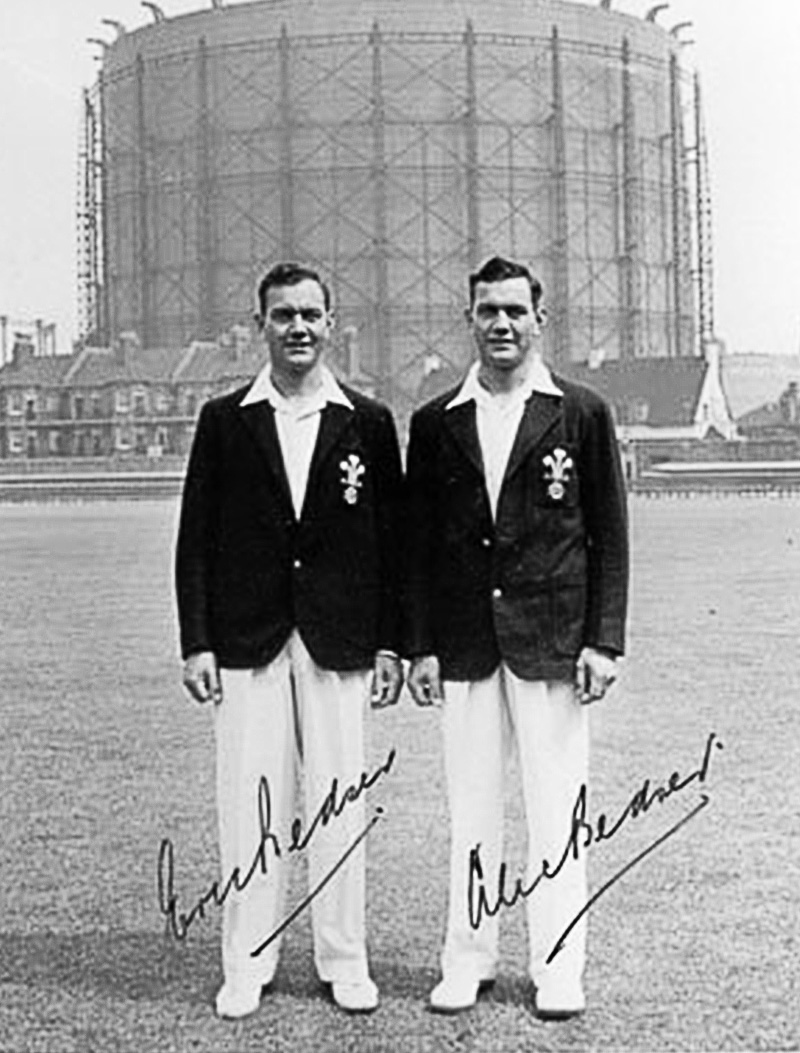

Sir Alec Bedser, London, October 2002:

|

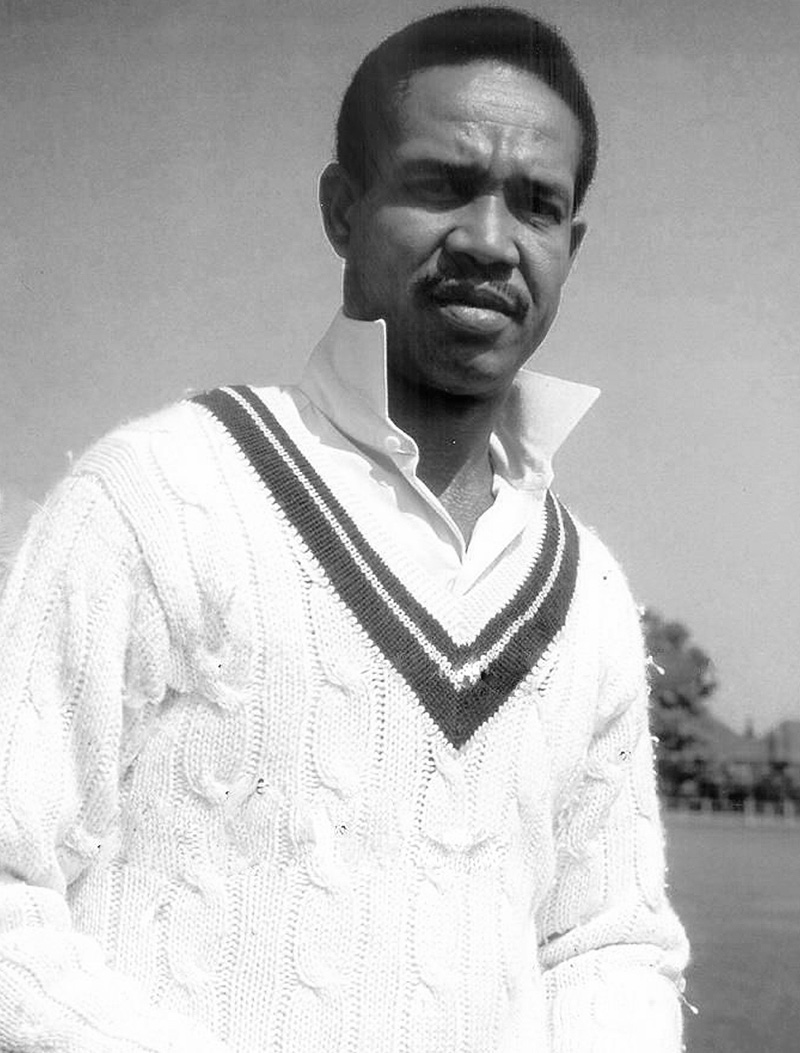

Sir Alec Bedser was one of the greatest bowlers of all time, tall and strongly built with enormous hands. When I met him and his twin brother Eric at the Souvenir shop of The Oval cricket ground, the gentle demeanor of Sir Alec gave an impression as if there was a halo around his head. After The Oval victory, Fazal Mahmood was called the Alec Bedser of Pakistan as their style of bowling was similar and. Upon hearing the compliment for Fazal, Bedser responded by saying, “I would be honored to be called the Fazal Mahmood of England.” Pakistan Test cricketer Wazir Mohammed believes that not only Fazal was faster in speed than Alec Bedser but was also better. Alec Bedser started his cricket career in 1946 and played till 1955 in 51 Tests taking 236 wickets at an average of 24.9. Fazal Mahmood began his Test career in 1952 and ended in 1962 and played in 34 Tests to capture 139 wickets at an average of 24.7. Fazal could not be selected for India to tour England in 1946 for being too young, otherwise his Test debut year would have been the same as that of Bedser. Fazal’s all-time regret was that had he gone with India on the Australian tour in 1947, he would surely have got the wicket of Sir Don Bradman. Alec Bedser appeared in 10 Test matches against Bradman. On his first encounter with him, Bedser bowled him for a duck in Australia in 1948. Then Bedser got Bradman five consecutive times. In all, he dismissed Bradman 6 times. Whereas Fazal dismissed the greatest batsman of England, Sir Len Hutton, with a world record of 364 runs twice out of his three appearances against Pakistan in 1954. Fazal would say, “If Hazare could get Bradman’s wicket, then why wouldn’t Fazal Mahmood?” I asked Sir Alec, what he thought of Fazal? Without hesitation, he replied, “Fazal was a great bowler. The best of his type. In those days not much cricket was played, had he been playing now with so much cricket going on, he would have got 1000 wickets in Tests.” When I narrated these remarks to Fazal, he was ecstatic.