Cricket has produced many great characters over the years, larger-than-life personalities who made their indelible mark on the cricket field. Cricket these days is a game for genuine athletes. Even 76-inch 200-pound fast bowlers are expected to hurl themselves around at the risk of season-threatening injury, in the vain hope sometimes of converting a four into a three. However, even the modern ‘percentage coaches’ admit that they like to see cricketers with character, and the game is in truth a test of just that. Some cricketers are able to achieve much by sheer force of personality, by grit, determination, genius, arrogance, or just sheer persistence.

Northern English counties especially have produced many great characters who rose from working class origins to become popular, sought-after players and even world-beaters. Ones that spring to mind are Fred Trueman, Geoff Boycott and Brian Close of Yorkshire. There have also been lesser players like Emmott Robinson and forbidding ones like Arthur Mitchell. Lancashire too has produced many great characters. ‘Bumble’ Lloyd, Brian Statham in his quiet way, Ken Higgs, Johnny Briggs, Cyril Washbrook.

Amongst these characters there stands out Jack Simmons, who became one of the leading allrounders in Lancashire’s history, one of its most colourful and popular characters, and a cricketer who brought great skill and much fun to any game of cricket.

He was also living evidence that you don’t have to be a muscle-Mary or a Gucci model to be an outstanding cricketer. Jack was well known for a protruding paunch eclipsed in girth amongst the counties only by Gloucestershire’s powerful batsman and future beloved umpire, David Shepherd. Jack liked a pint and large plate of fish and chips.

Jack, like many before and after him, was brought up in the Lancashire leagues. Of working-class origins like many in those parts – a very different species from the ‘gifted amateurs’ of counties like Kent and Sussex – Jack attended technical school, where his cricketing ability was first noticed. He became a draftsman and then a league professional, honing his skills more and more until he was finally noticed by his county. He took a pay cut for the pleasure and privilege of playing at county level. He was then 27 years old.

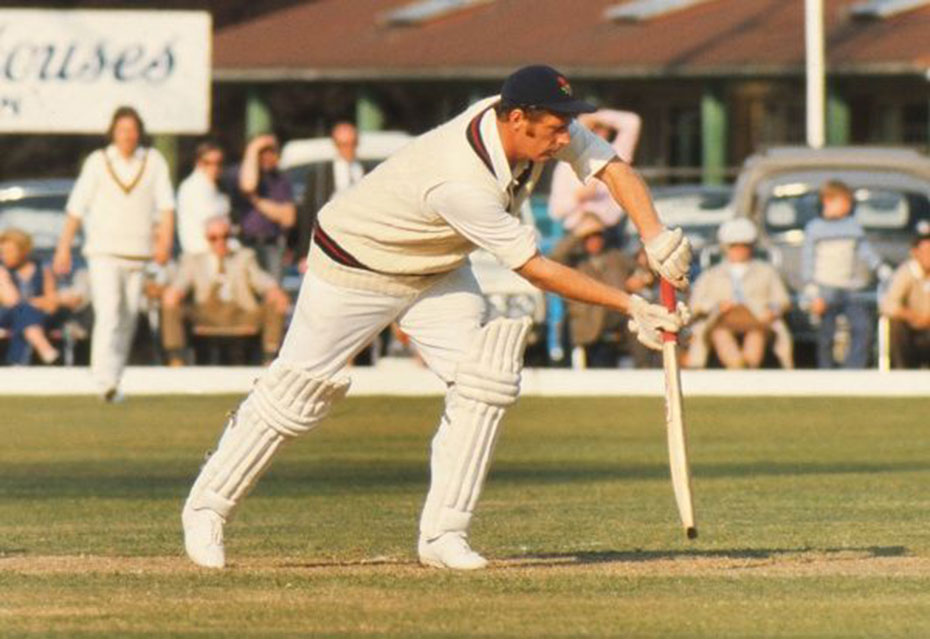

Jack was a pugnacious lower order batsman, capable of both aggression and obduracy according to the match situation and the bowling. But his main skill was that of the right-arm off-spinner. On usually damp northern pitches (at least during April to June – they tended to ‘flatten out’ during July-September, offering some dusty cracks as the pitch wore) the off-spinner could grip the surface and cause problems. Otherwise his job was to close up an end and prevent rapid scoring until the seamers were refreshed and came back to finish things off. Lancashire had good ones too, like Peter Lee, Peter Lever, and Ken Shuttleworth. Jack became a master of such skills. He did not flight the ball in a tempting loop, or at least only as rare variation. Rather he pushed it through quickly, with sharp spin nonetheless, tucking the batsman up and bowling to a tight and well-placed field. He came to be known as ‘flat Jack’ in recognition of the trajectory of his deliveries, but also in ironic reference to his stomach, which was the exact opposite of flat. But don’t be deceived. Those who played with Jack knew that he was strong and fit and a brilliant close catcher. He remained such until his late forties, and would have been happy to carry on as he was still playing well. He still goes strong at eighty.

Like a lot of spin-bowlers, Jack did not reach the height of his skill until his late twenties, when fast bowlers tend to start losing their edge of speed. Moreover, he floated into Lancashire’s view at a time when one-day cricket was advancing. The economy that Jack offered, as well as his canny (or was it uncanny?) understanding of batsmen’s minds, together with his ability to score quickly with the bat, made him a great candidate for one-day as well as three-day matches. Partnering with a similar cricketer, David Hughes, an economical left-arm spinner who could also bat, he formed the famous pair, ‘Simmo and Hughesy’, who became indispensable and highly successful as their county romped to three successive Gillette cups wins in 1970-2, and another in 1975, under their captain Jack Bond’s inspirational leadership. In fact we can attribute the survival and recognition of spin bowling in limited overs cricket to the advent of Simmo and Hughesy. Before them in one-day games spinners hunted in ones if at all, and counties packed their teams with seamers of rather moderate ability.

Around that time, Lancashire also had an excellent and fearless opening batsman in Barry Wood, also a man for all seasons, or not quite all seasons as we shall see. Wood scored a magnificent 90 against Lillee and Thomson in his first Test, and made the England tour of India and Pakistan in 1972-3, opening in four Tests. Now at that time Faroukh Engineer was Lancashire’s as well as India’s wicket-keeper, and was also Wood’s opening partner at Lancashire. Engineer knew Simmo and Hughesy’s bowling inside out like nobody else. He also kept well to India’s formidable trio of Bedi, Venkat and Chandrasekhar.

Wood had a tortured tour in which he was hard put to make double figures. Known as the best player of fast bowlers in England, Wood was all at sea against spinners, usually dismissed early by Bedi. He had no respite, as India generally opened with spin, or after a couple of overs, the spin trio would begin weaving their webs of deceit. The story goes that after one over from Bedi in which Wood was unable to lay bat on ball, playing and missing and with three shouts for leg before, Wood turned to Engineer and said, “’ey-oop, Faroukh, it’s not much like Simmo and Hughesy, is it?”.

True enough, it was a different world from spin-bowling at Manchester. Engineer would have been most amused. Wood, returning to Manchester with a tour test average of 13, was dubbed ‘The Star of India’. One can be reasonably certain that Jack had a hand in that joke.

Although Jack started late in county cricket, he played for 20 years aged 28-48, amassing more than 9000 runs and taking more than 1000 first class wickets and nearly 500 limited-overs wickets. He never played for England (they preferred John Emburey), but had six seasons with Tasmania, which at that time was not a first-class team. Jack, as Tasmania’s captain, was proud to lead them to first-class status, competing in Australia’s Sheffield Shield competition – and they have never looked back – from 1978.

Averaging more than 50 wickets a year in English first-class games, and more than 500 runs, Jack’s last full season at 47 years old was one of his most successful – he took 63 wickets that summer.

The most amazing match Jack played in, and to which he made a critical contribution, was probably the most famous Gillette Cup match ever played, the semi-final between Lancashire and Gloucestershire in 1971.

Gloucestershire, who had a good team, including one of the greatest allrounders, the South African Mike Procter, ground it out to 229-6, Procter making 65. Jack was easily Lancashire’s best bowler, taking two of the most valuable wickets, including the fat man opposite, the afore-mentioned David Shepherd, for only 25 runs in 12 overs (innings were 60 overs, not 50, in those days, and games took a long time to complete).

When Lancashire batted, they were in a parlous situation when Jack came to the wicket at 163-6. They still needed 67, and the light was already extremely poor. Procter, one of the world’s fastest and most difficult bowlers, was lurking ready to pounce.

Jack scored a crucial 25 out of 40 with his captain Bond, before getting out. Gloucestershire used their slow off-spinner, John Mortimore, in view of the declining light. Mortimore was the exact opposite of Jack; he bowled in a tempting loop and was a clever bowler, full of subtle variations.

Hughes came in, and by now the light was simply impossible by any standard. Another beloved umpire, Dicky Bird, was chirping away about going off. The other umpire Arthur Jepson, sorted him out by asking him what was up in the sky. “The moon, Arthur”, came the reply. “Now, if tha can see t’ moon, two hundred thousand miles away, we can play cricket. So shut thi’ mouth and let’s get on.” There were 25,000 people on the ground and the match had reached an unbearably exciting concluding passage.

Hughes proceed to clout Mortimore for 24 runs in an over, winning the match with a huge six that went out of the ground in full moonlight. It was 8.55pm and a miracle that anybody could see anything, let alone a cricket match. As it turned out, the fielders were the ones really in danger, and as for Procter, he took 0-38.

The final that year, against Kent, was also a thriller, Bond taking one of cricket’s most astonishing catches off Jack’s bowling when Asif Iqbal was winning the match for Kent single-handedly. Jack took a match-winning 3-48.

Stories of Jack’s eating exploits are legion, and, as David ‘Bumble’ Lloyd says, they are also true.

Great Harwood in Lancashire has a fish-and-chip shop that boasts a signature dish consisting of a fish perched happily on top of steak pudding, chips, peas, and gravy. It came about like this, as Jack himself said: “it started one night when I just couldn’t decide between meat pudding and fish, so I had both — with chips and mushy peas, of course.” The dish is called a ‘Simmo Special’.

On another occasion Lloyd was bemused when, after taking Jack to a chippy, the latter was seen outside sitting on a wall, finishing off his fish and chips. “Hey, Jack, why don’t you finish that at home?” “If I take it home,” he replied, “Jackie [his wife] won’t cook me any supper.”

Jack’s priorities in life are also illustrated by an occasion at the Southport ground, where lunch featured a famous gooseberry-and-cherry pie. Jack had just started eating one of these when the bell rang. Most would have abandoned the pie and hurried out onto the field to stand at second slip, but not Jack. He made sure he finished his pie in leisurely fashion. For an over after lunch, Lancashire fielded with ten men.

Twenty years and innumerable plates of fish and chips and cherry pies after his debut season in 1968, when he had delightedly clean bowled Colin Cowdrey, Jack called it a day. Jack’s benefit is good evidence of the high regard in which he was held by the public. It yielded 128,000 pounds in 1988, a record. Jack, always a team man, served as Chairman of Lancashire CCC from 1998 to 2008, when he was elected Chair of Cricket for the ECB. He was named one of Wisden’s five Cricketers of the Year in 1985. His contribution to the game and to the wellbeing of fish-and-chip vendors all over England will not be forgotten.