“Oh choro yar hammain kon janta hai” (Leave it friend who knows us) – I heard voice of The Oval’s Hero Fazal Mahmood when I rang him up in July 1997. There was a genuine satire in his voice which saddened me for a while. Fazal Mahmood, one of the foremost pioneers of Pakistan cricket, was actually complaining against the bureaucracy of Pakistan cricket which hardly used his services but always favoured ordinary and unethical cricketers to run the affairs of the game of Gentleman. This mentality still prevails in the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB).

I wanted to get appointment for an interview with the greatest exponent of leg-cutter whose magnificent performance against the MCC in December 1951 was instrumental to Pakistan’s admission in the then Imperial Cricket Council (ICC) and who was the prime architect of Pakistan’s victories in 1950’s against the giants of the game. “I know you Sir”, I said firmly and narrated some of his feats in international cricket which certainly delighted him. “Do you know all about me”, he asked.

“The upcoming cricket generation also wants to know more about you”, I responded. “Right! Come at 8 am next morning. Eight in the morning means 8 am”, Fazal commanded me like an army general. In the same evening I drove to Fazal Street in the modest vicinity of Ghari Shahu where he lived, only to locate his residence so that next morning I may not get late amid finding his place.

Next morning I was almost fifteen minutes before, spent the time near Fazal’s residence and pushed the doorbell exactly at 8am. The Oval’s Hero was sitting on his comfort chair close to the main gate. “Come in”, he responded loudly. As I entered inside I was thrilled to see an imposing tall, clean shaved man with green eyes, still erect in his early 70’s. Fazal looked at me for few seconds and extended his hand. Before I settled down and introduced myself, Fazal hurled a volley of irrelevant questions at me.

“Do you know about the Kashmir issue? Do you know about China? Do you see those birds? Fazal stood up from his chair, guided me to his small garden to show the nests of the birds on a tree. “In fact they are the inhabitants of this house I just look after them”, Fazal informed me. As I was puzzled and thinking as if I was wasting my time, Fazal asked me yet another irrelevant question: “Do you know about farming”? That confused me completely. “I have come here to talk on cricket and this grand old man is distracting me”, I thought to myself.

Then Fazal hurled another but relevant question: “Do you know Keith Miller”? “Who doesn’t know the great Australian all-rounder”, I asked. “Do you know about Three W’s? I named Clyde Walcott, Frank Worrell and Everton Weeks. “Do you know who is the first Pakistani named in the Wisden, the Bible of Cricket”? I was ready for that question and told him that it was you. He smiled and his green eyes glimmered with absolute pride. “Now go ahead”, he allowed me to start the interview.

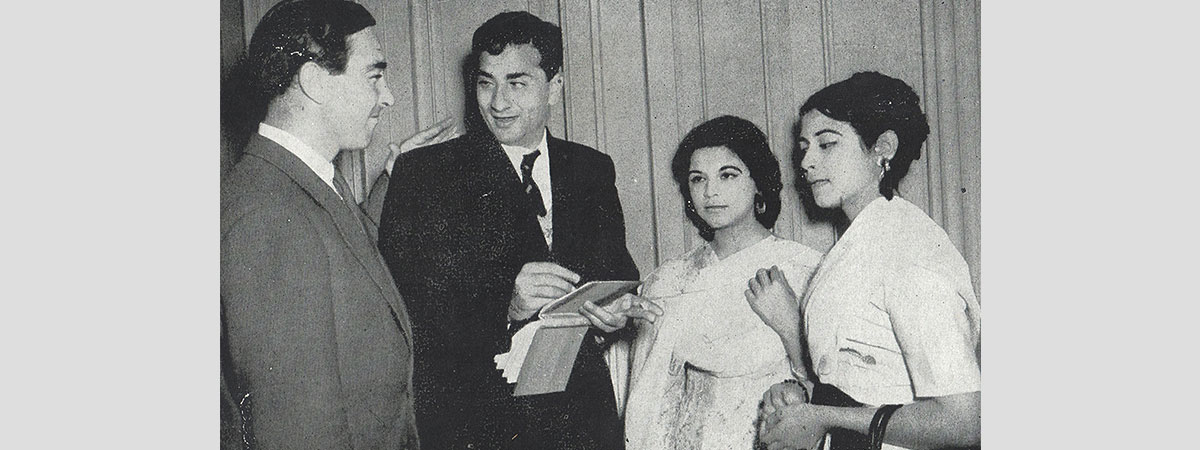

Fazal Mahmood and Denis Compton are talking while an aspirant is waiting for the autograph.

The Oval’s hero was not only testing my interest and knowledge about cricket but my patience as well. He wasn’t prepared to waste his time on an average sports journalist. I studied in the best institutions of Pakistan and joined journalism by default and was not an ordinary journalist. Fazal’s yardstick for assessing people was fairly high.

Fazal was fanatic about cricket since childhood. He was a student of nine class when one day, his teacher gave a test to the class for the next day with a warning that anybody found absent would be punished. To Fazal’s hard luck, he had to play a club cricket match the following day.

On the next day when he was tucking into his breakfast, he thought for a minute and then went to play the match. His performance was brilliant. He grabbed five wickets to help his team to win the match. The late Civil & Military Gazette printed Fazal’s picture with a headline ‘School boy does wonders’. Fazal clipped the news from the newspaper and went to school.

The teacher ordered Fazal to stand up. Brandishing a stick, he came over to Fazal who, trembling with fear, stretched his hand out to receive the beating. There laid the clipping on the palm. The teacher took it, read it and went out of the class. After a while Fazal was called into the headmasters’ office. The headmaster ordered the students to assemble in the ground.

As little Fazal reached the school ground accompanying with the headmaster he was asked to stand on a table. The headmaster announced to the students about Fazal’s feat. He was showered with pats and the school was closed down for the rest of the day. When Fazal narrated me the incident I could not help feeling a twinge of envy for a man who broke England’s myth as cricket’s God at The Oval in August 1954.

Fazal belonged to an educated family of Lahore. His father was a professor at Islamia College, Lahore who nurtured his son to become Pakistan’s first true cricketing celebrity. Fazal mastered in Economics from Punjab University. Before the creation of Pakistan, Fazal played for Northern India. His outstanding performance in Ranji Trophy matches were noticed by greats of the game.

Nawab Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi, former captain of Indian cricket team, for young generation grandfather of Bollywood star Saif Ali Khan, was a great supporter of Fazal. He had watched him bowling in the Ranji Trophy matches. Pataudi wanted Fazal in the All-India team on England tour in 1946. But the selectors thought he was too young.

The team returned after a disastrous tour of England and played a match with Rest of Indian XI at the Feroze Shah Kotla ground in Delhi. Fazal and Nazar Mohammed were selected to play for the Rest. Both Pataudi and Prince Duleepsinghji watched Fazal bowling in the match. Renowned sports journalist late Sultan F. Hussain who was reporting the match overheard their conversation.

According to him, “Prince said he is good. He should romp home. I wish I could be in Sydney to watch him bowl on that track. He could be lethal”. Fazal took seven wickets and next day Hindu newspaper Partab carried the story by headlining ‘Fazalki jai’ (victory for Fazal). Few days after the match, Quaid-e-Azam came to Islamia College where Fazal studied.

The Principal introduced Fazal with Quaid saying: “Sir this boy is doing wonders”. Quaid, who himself was an ardent follower of cricket, hugged Fazal saying “Keep it up young man, Keep it up”.

Fazal’s performance against All India XI convinced selectors to include him in the Indian team’s camp at Poona for the Australian tour in late 1947. He attended the camp which was concluded and the players were to reassemble in October.

On his way back to Lahore, Fazal witnessed the carnage that erupted after the announcement of the Partition. In September, Fazal received call from the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) but he declined the offer. Later he was persuaded by Nawab Iftikhar Hussain Mamdot who was the chief minister of Punjab and later became the founding president of the Board of Control for Cricket in Pakistan (BCCP). “Manny Bhai, do you want me to brig laurels for Indians”, Fazal asked Mamdot.

Fazal was friendly with Mamdot whose family had founded the famous Mamdot Club in Lahore for which Fazal played. Fazal would call Mamdot Manny Bhai. The obituary of Fazal in the London Times paid him the supreme compliment by saying that had Fazal gone on that tour (Australia) it was unlikely that Don Bradman would have had the average (178.75) in the series.

Fazal along with some other fellow cricketers and organizers of the game were instrumental in the formation of the BCCP. He would narrate the story behind the formation of the BCCP. “We persuaded Nawab Mamdot to become the president of the Board and also forwarded the name of KC Collector, head of Parsi Gymkhana Cricket Club in Karachi, as secretary. If anyone claims that he pioneered the cricket board, he is wrong. We are the people”, Fazal would say proudly.

But surely Fazal’s shinning hour was the Oval. Victories have been won. Difficult matches have been extricated from the jaws of defeat. But the victory at the Oval is a victory above all victories. It brought joy to millions of Pakistanis who were still reeling from the pain of bloodshed during the Partition.

It was a perfect independence gift to the new born country during the month of August. Pakistan were dubbed Babes of cricket by the English media on that tour. At The Oval, Wazir Mohammed, Abdul Hafeez Kardar, Zulfiqar Ahmed and Mahmood Hussain also performed well. Imtiaz Ahmed was magnificent in taking seven catches behind the stumps.

Fazal amongst the fans after the Oval victory.

Late Hanif Mohammed’s direct throw to get rid of Jim McConnon was the last nail in England’s coffin. This cricketing win destroyed the myth of Imperial invincibility and Fazal proved his words he had uttered to Dennis Compton few days before the Oval Test while travelling with him in a car from Trent Bridge to London. “Yes! We can do it.

”And all this owed to the main architect of this victory, the hero Fazal who with his brilliant 12-99 performed the miracle ever to be remembered. It is a pity that satellite channels were not available then and today we don’t have any available record to watch Fazal’s intricate variations of line, length, swerve and leg-cutters which he delivered with stunning accuracy. It would have been a visual lesson for posterity. The BBC only had the last minutes of the Oval Test which shows Fazal bowling and Hanif smartly throwing at the wicket to get last English batsman McConnon being run out.

Fazal was evaluating the tactics of English captain and their batsmen. He was reading the changing condition of the pitch as well during all the playing days of The Oval Test. He was completely focused on his bowling. Even the rain couldn’t distract his focus. Fazal’s own description of planning, execution and of exultation in his biography ‘From Dusk to Dawn’ which I authored, is worth reading. He had stumbled across that Sir Len Hutton had limitation in going well forward on an incoming ball. When the master batsman was rapped on the pads thrice in four balls he then used long handle against Fazal, in sheer frustration.

“When Hutton was running between wickets and came to my end, I applied psychological pressure and looking at him said – This is not Hutton like. When he (Hutton) came to the other end I decided to bowl that special concealed ball, knowing that if I were missed I would not be able to tame the lion, the world record holder.

So, I maintained my accuracy, speed, and rotation of the ball, inviting him to play into the covers, yet giving some room in between bat and ball. Hutton played through the covers, but the ball found his outer edge and went into the safe hands of Imtiaz. I was jubilant. My appeal was apparently very closely listened to in the dressing room and in the streets of Pakistan, particularly in my hometown Lahore”.

At one stage England were 109 for 2 and needed just 59 to win. With Peter May and Denis Compton were at the crease, England looked on the verge of victory. Fazal who was minutely evaluating the proceedings, noticed Kardar showing gestures of replacing him (Fazal) at the end of Mahmood Hussain’s over on the fourth day.

He approached him and literally snatched the ball. “Do you want to lose the match”, Fazal warned Kardar who looked surprised. Fazal got the prized wicket of Peter May. He was bowling the last over on the fourth day when he had a dig at Kardar. “Hafeez what if I get Dennis out”? Kardar replied in typical Punjabi – ‘Fere the jithjanwanghain’. Compton had managed to survive amid three drop catches on Fazal’s bowling who showed neither irritation nor disappointment, but simply seemed eager to bowl the next ball.

During this innings Fazal discovered and exploited a patch on the pitch which was a great testimony to his deadly accuracy. Every time, Fazal hit the spot Compton would come to mend it with his bat. Between the overs, the earth on the spot shifted. Seeing that shift Fazal applied a psychological ploy against indomitable Compton. “Now you can’t put the earth back”. He told the batsman.

Fazal bowled a very fast in-cutter to Compton who edged it and was caught behind. The match had been virtually won. That was the determination of a bowler who never played for money. His only pride was the green Pakistani blazer baring an Eagle as a symbol.

On the fifth morning England showed some resistance in the face of left-hander John Wardle who blocked and ducked in search of a draw. But Fazal had planned to end the match in the first session. “You put your right foot here, left foot there, unfold your hands and stand ready for a catch. The ball will come right into your hands and you just grab it,” Fazal told Shujauddin who was asked to field at short square-leg. Soon a leg-cutter of Wardle’s bat found its way into Shujauddin’s hands who did not have to move a centimetre, and thirty minutes later Pakistan became the first Test nation to remain undefeated in their first-ever Test series on the British shores.

It is no wonder that Fazal’s 12-99 at the Oval was rated by an article in an English Newspapers in 2005 as the best ever seen on the ground. Compton had also tremendous praise for him: “Fazal, simply unplayable in his day. My most difficult and memorable innings was at the Oval against him where I scored 53 in 1954”, he once said in his interview.

Flamboyant Keith Miller paid great tribute to Fazal in his letter dated: 26/10/98 in which he has rated Fazal’s 13 for 114 against them at Karachi in 1956 as the best he has ever seen. “Your performance was even better than J.M. Laker’s remarkable 19 wickets at the Old Trafford”, he wrote. I possess Keith’s letter. The incomparable Neil Harvey said: “Fazal could make the ball talk on a matting wicket.” But the tribute to all tributes was the great man himself Sir Alec Bedser as quoted: “If cricket was played as much in those days as now, Fazal would have taken a thousand wickets.”

On Pakistan’s Tour of England of 1962 Fazal was taken to dinner by Sir Len Hutton during the Trent Bridge Test. Over coffee Sir Hutton asked: “Fazal, it has been eight years since the Oval Test. I have been thinking about what you did with the ball and I have not yet been able to understand. Would you tell me how you bowled that particular ball which got me out twice in the Oval Test?” It was the greatest compliment Fazal could have received as a player. Sir Len Hutton, the All Time great opening batsman, the only Englishman to have held the world Test record of 364, paying such a great tribute should be more than enough to place Fazal at the top of the all time ladder.

Fazal’s stamina was as robust as that of a long-distance runner. It was the result of a strict regime he followed from his school days. From his teens he had regulated his waking and sleeping habits amid his fierce determination. He would do 10 kilometres daily jog and 500 jumps with a skipping rope early in the morning.

And of course daily two to three hours net practice in the afternoon. He used to swim daily a series of lengths at a stretch in the swimming pool of King Edward Medical College, Lahore. The swimming exercise was a great boom to Fazal’s health as throughout his cricketing career he never felt the slightest pain in his groin, the tenderest muscle in the body. He was always a super fit cricketer. Kardar would include an extra batsman in the final XI assuming that in Fazal’s presence he didn’t need an extra bowler.

In the Third Test at Sabina Park, Kingston, Jamaica in 1958 where Sobers surpassed Len Hutton and made new world record scoring 365 Mahmood Hussain was injured in his very first over. Fazal bowled 85.2 overs unchanged throughout the innings of a Test Match, under a blazing Jamaican sun, which is a world record for a pace bowler. Fazal’s figures were: 85.2-20-247-2. Khan Mohammed’s figures were: 54-5-259-0.

Years later Fazal returned to Georgetown University in Washington, DC, where he was studying advanced administration, a woman who had helped him with his thesis asked if she could touch him. Fazal was startled. The woman then told him she had been at the stadium in Jamaica when he bowled that marathon spell. “I was wondering what metal you are made of,” she remarked.

After retirement when Fazal was recalled amid disastrous England tour in 1962. Pakistan had lost first three Tests of the five-match series. Uproar followed in the media and on persistent public demand Fazal was requested by the BCCP to go to England to reinforce the depleted Pakistan attack.

Fazal was away from active cricket for two years but he responded the national cause. That’s another story that he got such rash treatment by the captain who used the great bowler ruthlessly. In his last two Tests of the career, Fazal bowled 63, 60 and 49 overs in three innings. He bowled 45 overs on one day –one day! – of the fourth Test. Sir Len Hutton, writing an exclusive column in The Pakistan Times wrote: “Burki worked on him so hard that had the big police officer from Lahore been a work horse, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty on Animals would have stepped in and demanded that he be given a rest”.

Fazal was the strike bowler of the Pakistan cricket team, a distinction he carried till his exit from international cricket. Both Khan Mohammed and Mahmood Hussain were his bowling partners. In 40 Tests both have less wickets 122 against Fazal’s 139. And extraordinarily Fazal bowled 9834 balls to their combined 9067 balls in Tests. It requires a giant to do the job of two men.

Players | Tests | Balls | Maidens | Runs | Wickets | Average |

Khan Mohammad | 13 | 3157 | 152 | 1292 | 54 | 23.96 |

Mahmood Hussain | 27 | 5910 | 230 | 2628 | 68 | 38.64 |

Fazal Mahmood | 34 | 9834 | 548 | 3434 | 139 | 24.70 |

Fazal’s 139 wickets were not freebies. Ninety three of his wickets were specialist batsmen. Among the cream: Sir Len Hutton, Neil Harvey, Denis Compton, Clyde Walcott, Conrad Hunt, Polly Umrigar, Vizay Manjrekar and Gary Sobers. No bowler had a promising start and no one did more than Fazal, with 65 wickets in the seven wins he played in.

Nature had endowed Fazal with a 6.2 feet frame, long arms and legs, supple wrists, and beautiful long fingers. As all champions are manufactured from the Magic Mantra “Talent, Technique, Temperament, and Training” the base being the technique – the method. Nature had also gifted Fazal with all these traits which honed him to become the first super star of Pakistan cricket and a role model for the generations to come.

He had a rhythmic run up, a perfect delivery action, left arm strictly at twelve O’clock position which helped him achieve pin point accuracy. Armed with it he added to his repertoire, mastering the in-swing, out-swing and the beautiful swerve ball which rewarded him so well throughout his career. But the delivery, with which he targeted so many great batsmen, was his in-swinging leg-cutter.

Fazal’s detractors believe that he was a self-centred person who wished others to listen and praise his achievements. During my over 25 years in sports journalism I have come across cricketers who cherish to narrate their smallest achievements in Test or even in first-class cricket. What to talk about great Fazal who is the only Pakistani cricketer to have won a place in Wisden in 1955 on his first appearance on English soil. Fazal was the prime architect in all Pakistan’s four victories – 1952-1959. He showed Pakistan cricket how to win. His 12 or more wickets in Test Match victories in the formative years of Pakistan cricket means that he single-handedly won matches. He is probably the only pace bowler in the world who has taken 12 or more wickets against four countries he played against, Lucknow against India (1952)– The Oval against England (1954) – Karachi against Australia (1956) and Dacca against the West Indies (1958). New Zealand being the only country Fazal couldn’t complete a haul of 12 wickets. Murlitharan is the only spinner who has completed this haul against six different countries. But Murli played Test Cricket against ten countries as against Fazal who played against only five.

Fazal would often discuss plight of national cricket. Every time I noticed him restless. He wanted to contribute for Pakistan cricket. One fine morning, in late 1998, he ranged me up and directed me to accompany him to the Gaddafi Stadium where national team camp was in progress. As Fazal and I were driving towards the Gaddafi Stadium I asked him as what provoked him to go there. “Shoaib Akhtar bowls very fast but can’t bowl an in-coming delivery. He is such a fast bowler that if learned to bring the ball in he would be more deadly”, Fazal educated me.

As we entered the Gaddafi Stadium ground, Fazal stopped near the ropes at the boundary line and called Aamir Sohail who was the captain of the national team. Aamir came running after all great Fazal was around. Fazal sought Aamir’s permission which surprised the left-hander.

“Sir you need not to take permission from anyone”, Aamir protested mildly. Fazal walked inside where everyone including Wasim Akram, Saeed Anwar, Salim Malik and Moin Khan greeted him. Fazal called Shoaib Akhtar and asked him to bowl an in-swinger. Shoaib wasn’t ready for that when he looked at Fazal, clad in cricket kit and wearing his prayer cap. Shoaib looked a bit puzzled and murmured: “Sir, it’s hard for me to bowl an in-swinger”.

Fazal then taught him how to grip the ball while bowling an in-swinger. Fazal himself took the position of the umpire at the non-striker end. Saeed Anwar was batting. With right grip on the ball Shoaib started bowling in-swinger after few deliveries. Then Fazal took upon himself the coaching job and after every delivery kept on telling Shoaib to bowl in a particular area.

Saeed Anwar was batting and was beaten a couple of times on the leg-stump. On one delivery Saeed came forward but was beaten and Fazal shouted: “Saeed stop in the same position and see your leg stump”, Fazal demanded of Saeed. “Sir, it is exposed”, Saeed replied.

In one brief session the great Fazal taught the fast bowler how to ball an in-swing and the batsman how to save his leg stump while playing an incoming ball. He then told Shoaib that I will charge a heavy fee from you for my coaching. “I want you to get Sachin Tendulkar bowled on an incoming ball”, Fazal revealed his amazing fee.

Credit to Shoaib who worked hard on his in-coming ball and some weeks later bowled both Tendulkar and Rahul Dravid on back to back deliveries in the Asian Test Championship match at Culcutta. Fazal was the most delighted person in the world.

It is an irony that Pakistan Cricket Board didn’t utilize Fazal Mahmood’s expertise to hone upcoming talent. Apart from a short stint when Abdul Hafeez Kardar headed the then BCCP, Fazal was a national selector. In early 1980’s Fazal conducted coaching camps which produced many a Test cricketers for Pakistan. In early 2000’s former chairman of PCB Lt-General (R) Tauqir Zia gave Fazal some assignment for a brief period on meagre remuneration while mediocre former Test cricketers in the Board were getting exorbitant monthly salaries. This perturbed me and I personally approached Gen (R) Tauqir and requested him to look after great Fazal well. The General obliged!

Rivalry between Fazal and Hafeez Kardar is known to the old generation but that rivalry was just outside the field. They studied in the same college before Kardar went to England for higher studies. “Nazar, Imtiaz and I were friendly with Kardar and would conveniently exchange typical Lahori banters with one another.

Somehow, we all felt that after his return from England Hafeez demanded respect which at least I didn’t accept. We both maintained an healthy rivalry. “I would often dig at him, Hafeez you will lead the team in and I shall lead it back – and I proved my point in all four victories Pakistan won under his captaincy”, Fazal would say.

Fazal recalled how Kardar ensured his non-selection in the match against the MCC at Karachi Gymkhana ground. “A day before the match, while I was in my hotel room in Karachi, I learned through radio news that I had not been selected in the team. I could not believe and was crestfallen,” wrote Fazal in his autobiography. Dr. Dilawar Hussain, a national selector, called me at night and directed to come to the ground in the morning for the game.

In fact Dilawar lied to the other selectors that the Board Chairman Justice A. R. Cornelius had ordered Fazal’s selection. By lunch on day one, England were five down and Fazal had picked four. “Son, you have saved me from the gallows,” said Dilawar to Fazal as he walked into the pavilion for lunch. Three days later Fazal hit the winning runs that would secure Pakistan Test status.

Fazal whose forefathers were of the Khilji tribe from Turkmenistan, and came to India somewhere in the 19th century, was arguably one of the most handsomest cricketers of all times. He had naughty eyes and a lovely smile. Hollywood actress Ava Garden wanted to dance with Fazal at Lahore’s Gymkhana Club. Noor Jehan allegedly sang a song about his hair. He had film offers from both sides of the Wagha border.

On Batoryship to England for the 1954 tour, Fazal would work out during morning and was a big hunk of life and love on the dance floor at night. Australian all-rounder late Richie Benaud wrote in his book: “He could not take his eyes off Fazal’s face being the handsomest man he had ever seen”.

Fazal played cricket in an era when there was no television. People loved listening to the radio commentary by Omer Kureshi and Jamsheed Marker. In the city streets, the proceedings of the match were written on the blackboard with a chalk. Those were beautiful old days. Fazal would always duck my question about his flamboyance life about which I had heard so many anecdotes from his contemporaries.

My journalistic instinct wouldn’t be satisfied from his avoidance. So one day I decided to have a dig on him and it worked. “Sir, Imran Khan is a glamorous cricketer and very popular among the women”, I provoked Fazal who didn’t take it easily. “Imran played cricket in an era of advanced print and electronic media which, besides his cricketing talent, made him glamorous. I played cricket in an era when there was no television and even newspapers would only publish our black & white photos. Even in those conservative times I had been followed by ladies of good families and actresses of the film industry both in Pakistan and India. Some women would knit sweaters for me and bring lunch from their houses during the course of a Test match. Often I would listen some lady asking me when the team would return for lunch – “Fazal I have brought home cooked Aaloo wala Parathey and Kebabs for you”, Fazal would make a comparison with a fair amount of logic.

Fazal had an interesting encounter with late Indira Ghandi on the 1952 Indian tour. Later she became prime minister of India. After scoring painstaking 27 runs in the second innings of the Delhi Test he returned and sat in the VIP stand with pads on when he heard a gorgeous-looking lady saying: “You can’t win, come what may”, the lady said in aimpish tone. Fazal brushed her off saying if she wanted Pakistan to beat India come to Lucknow. But persisting with her claims, she went away smiling. An official of the Pakistan High Commission later informed Fazal that she was Indira Ghandi, daughter of the then Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. After Pakistan won the Lucknow Test, Fazal received a bouquet with an ‘anonymous’ card.

Fazal possessed an inimitable charisma which was hard to ignore even by the exalted dignitaries. During the Lord’s Test of 1954, the customary ceremony, to introduce the visiting team to Queen Elizabeth, was held at Buckingham Palace due to rain. The Queen was amazed to see Fazal while shaking hand with him. After finishing with the last man in the row Queen returned to Fazal and asked him: “How come you have green eyes while others don’t have”. “Your Majesty, people from northern areas of Pakistan do have green eyes”, Fazal educated the Queen whose ancestral ruled undivided India for over nearly hundred years. As the tour progressed Fazal was also invited to attend a Queen’s Royal Garden Party. His contemporaries suggest that it was due to Princess Margaret (Queen’s younger sister) that Fazal was invited to the annual event for several years to come.

Fazal was a traditionalist who loved values and maintained them strictly. Eagle was the insignia of the BCCP which was also on the national blazer the cricketers of the formative years donned. Later BCCP was renamed PCB and Star was placed by Eagle. Fazal never liked those illogical changes. “Both decisions were bad – BCCP to PCB and Eagle to Star”, Fazal would often say. He was not mentally prepared to accept star instead of Eagle. “We had Allama Iqbal’s Eagle on our blazer which taught us that sky is the limit.

We played our cricket with a commitment and determination to remain on top amid immense spirit of nationalism and we toiled our blood to bring laurels for the country. Eagle was Allama Iqbal’s mascot for the Muslims and it should had not been changed”, Fazal would say with a visible anger.

Fazal played in an era when Test cricketers were paid Rs. 5 for daily allowance. “We would use the money to keep our kits neat and clean. Those who had no bicycles would hire a Tonga to reach the ground in time during international matches”, Fazal would recall. Thirty rupees for a Test match may seem ridiculous today but money was never an attraction for Test cricketers of 50’s who prided themselves in donning Green Blazer.

Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar had special affection with Fazal. During the 2004 series, he expressed his desire to meet the great cricketer. Fazal was invited into the dressing room of the Indian team at the Gaddafi Stadium, Lahore where he met with the Indian cricketers. Tendulkar informed Fazal that he had heard a lot about him (Fazal) from his seniors at the Bombay’s Wankhede Stadium.

New generation of our fast bowlers could learn discipline from a flamboyant, charismatic and extremely popular Fazal who had been leading the team’s pace attack and had almost single-handedly won matches for Pakistan. He was glamourous while remaining a respectable figure and a true role model for the generations to come. Fazal was a true Pakistani, true legend, son of the soil and pride of Pakistan. I consider myself lucky that I enjoyed his company and educated myself from his incomparable cricket knowledge. I also feel pride that I wrote From Dusk to Dawn, the biography of great Fazal. Working with Fazal was a wonderful experience. May Allah rest his soul in eternal peace (Aameen).