I don’t know if a special comet or star appeared the night Derek Underwood was born, but, if not, it had no business not doing so.

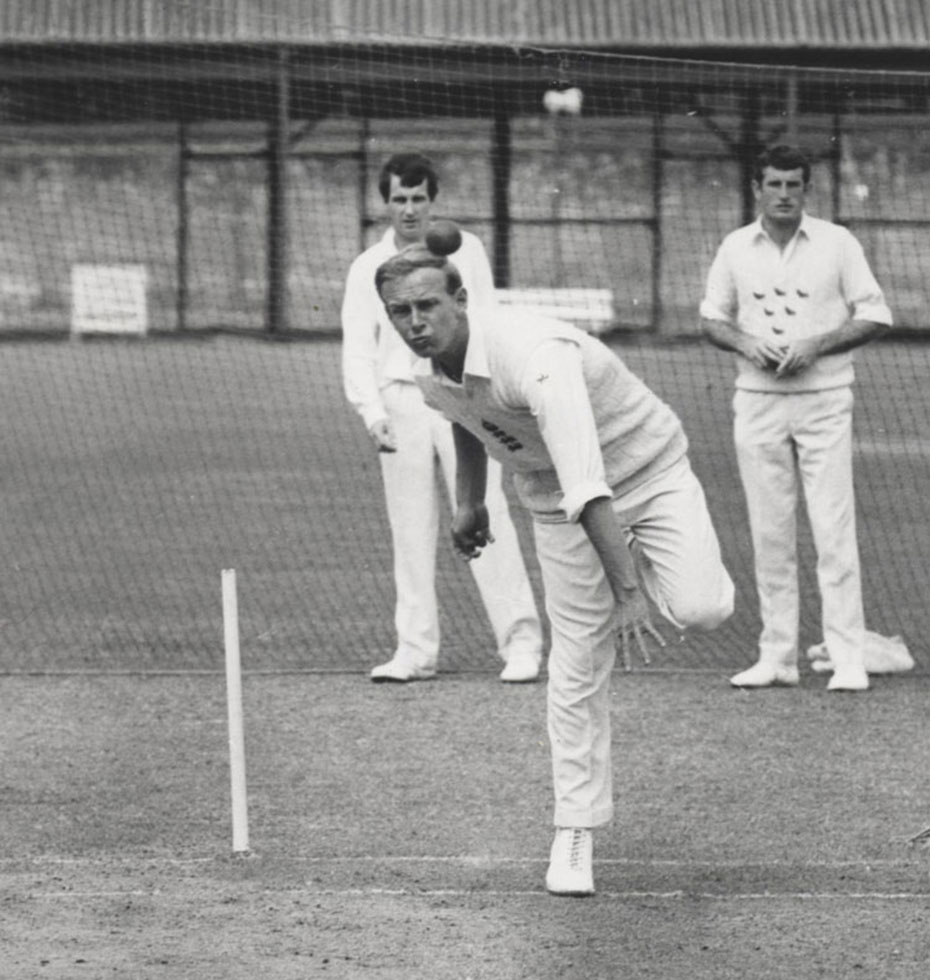

‘Deadly’, as he came to be, appropriately, named, was one of the most venomously intelligent bowlers, certainly spin bowlers, there has ever been. I don’t say ‘slow’ bowlers, because in fact Underwood bowled at medium pace off a longish, rhythmical run, left arm round the wicket. He was especially dangerous in damp, or in dry, dusty, conditions. He was a genuine spinner of the cricket ball, and not, as some said, a purveyor of cutters. It was said that when he bowled one could hear the ball fizz through the air. They said the same of Jim Laker, and nobody could doubt big Jim’s ability to spin a cricket ball.

I recall, when I was a teenager, watching Underwood bowling for England on television. Our Mum would be busy in the kitchen, but she loved watching Underwood. When he came on, we would call her, “Underwood’s on, Mum!’. And she would come rushing into the living room, wiping her hands on a tea towel, and watch several overs before returning to finish cooking. “Why do you like Underwood, Mum?”, we would ask. “Oh, I don’t know, love, he’s just very interesting to watch. You know, every ball is different.” Well, yes, you can say that again. You would have to face him to know how very true that was, because the differences were subtle.

Underwood developed far earlier than a spin bowler has any right to, with what John Arlott called a ‘an old head on young shoulders’ – an uncanny ability to work a batsman over, frustrate, and deceive him. In his first test, I recall, against the West Indies, he dismissed Rohan Kanhai by holding back, ever so slightly, a delivery outside off that had Kanhai driving and caught low at mid-off. He did not have success in those first two tests, yet there were signs of unusual early ability.

Underwood remains the youngest bowler to take 100 wickets in an English county season, at just 17 years old, in 1963. He was the youngest bowler since Wilfred Rhodes to take 100 Test wickets and 1000 first-class wickets, at only 25.

Few who saw it will forget the 5th Test between England and Australia at The Oval in 1968. On the final day England needed five wickets to beat Australia, whose target of 353 looked impossible, given they were 13 for 2 overnight. They progressed to around 100 for 5, and Underwood had at that point dismissed Redpath, Ian Chappell, and Walters. The heavens opened, and torrential rain made the ground a lake by 2pm. Most predictions were that there would be no further play that day. During the course of the afternoon the weather cleared but the ground was still very wet. Appeals were made to what was by then a sparse crowd to help to mop up the water.

Pitches were not covered in those days, and conditions were very wet indeed, but the crowd assisted the ground staff to dry things out, using every known sponging device, and, miraculously, play was able to begin 75 minutes before the scheduled close. Nobody gave England much chance of winning the match, and for 40 minutes, little happened, the pitch behaving like a pudding as Inverarity and Jarman held the fort with no difficulty. But the pitch was drying out, and D’Oliveira suddenly produced a ball that somehow dislodged Jarman’s off bail, as everyone was wondering if he was LBW or caught behind. Anyway, he was out and Cowdrey whipped Underwood back on.

In his first over of the spell Underwood had Mallett caught by Brown at short leg off a ball that stopped in the pitch. In his next over he dismissed McKenzie in an identical fashion. It was 110 for 8, and there were about 20 minutes to go before the close. Inverarity, who had batted right through the innings for a half-century, clung on desperately with Gleeson, until Gleeson became Underwood’s sixth victim, bowled by an arm ball. Connolly came in to join Inverarity, who kept the strike and faced what was to be the last over. The third ball, another arm ball, found Inverarity shouldering arms, and he was LBW. England had won, and Underwood had taken 7 for 50, the last four in 27 balls for six runs.

Underwood’s other notable achievement in Tests was his ten-wicket haul (4-37 and 6-45) for England against Australia in the famous ‘fuserium’ Test at Leeds in 1972, a match for which Underwood had been brought back into the side in place of Norman Gifford. The Australians claimed that the pitch, affected by a fungus, had been prepared for Underwood. The record appears to indicate otherwise, but Underwood was certainly helped by the conditions. England won by nine wickets as Australia were kept on the wrack by Underwood and Illingworth, bowled out for 146 and 136.

Underwood made his Test debut in 1966, just after his 21st birthday. His England career spanned 16 years until 1982, and he would certainly have taken 300 wickets had he not joined Packer’s World Series and then the rebel tour to South Africa. He took 297 Test wickets at 25.83 apiece, taking five in an innings on 17 occasions, and ten in a match on six occasions. He was the world’s number one bowler from September 1968 to August 1973.

In first class cricket he took 2465 wickets at an incredible average of 20.38. He took five in an innings on no less than 153 occasions, and ten in a match on 47 occasions. Underwood was instrumental in Kent’s championship victory in 1970, its first pennant since 1913, during the days of Colin Blythe, and he took 100 wickets in a season on nine occasions. He retired in 1987 at the age of 42, subsequently becoming President of the MCC.

Underwood was not an all-rounder and his batting skills usually ensured his appearance at no 10 or no 11. Nonetheless, his county colleague Alan Dixon records that, being frequently employed as a nightwatchman, he never failed to block it out to the close, and in his last season, aged 42, he went in as nightwatchman and the next day completed his first century. As an England nightwatchman he faced the most hostile bowling without flinching, and without, so far as I can recall, getting out. He also once scored a charming 45 not out for England against Australia. He was not the greatest fielder, being clearly identified by his splayed feet, but had a safe pair of hands, taking more catches off his own bowling than anyone except Alan Knott.

Knott was essential to Underwood’s success, especially on damp pitches where he would make the ball rear spitefully off the pitch, causing as many problems for a wicket-keeper, standing-up, as for a batsman. There are many accounts of Knott taking seemingly impossible catches and takes off balls that reared even to head height.

Knott grew up with Underwood in Kent cricket from an early age, had an instinctive understanding of him, appearing to be able to read his mind.

The secret of Underwood’s success was his ability to make the ball lift and deviate in damp conditions in which he was well-nigh unplayable. He naturally enjoyed less success on overseas wickets, which offered him less assistance, but he was nonetheless a challenge due to his other great merit, which was his unfailing accuracy. There was no waiting for the bad ball when Underwood was bowling – you would likely wait all day. Underwood hated to be hit, and prided himself on keeping an end very tight. Those who tried to hit him off his length usually perished, as, notably, did the Australian wicket-keeper, Rod Marsh, on numerous occasions. Underwood’s Test economy rate of 2.10 runs per over speaks for itself.

Underwood’s accuracy could seem almost metronomic, and it was sometimes said he could wear a hole in a pitch just by landing the ball on the same spot. But his variations were subtle and he often deceived the batsman with variations of pace as well as length and line. His pace varied from below medium to above medium, and he would adjust it according to the conditions. Occasionally he would even bowl genuinely slow with a pleasing loop. While he bowled over the wicket at the start of his career, he soon turned to round the wicket, and as a result claimed many wickets with the arm ball that did not turn but skidded into the batsman’s pads, or made them a candidate for a bat-pad catch at short leg. This ball was as lethal as the ball that lifted and turned, bringing slips and gully, as well as the keeper, constantly into play.

Mark Nicholas remembers Barry Richards, the best batsman in the world at the time, saying that Underwood bowled Hampshire out for next to nothing on a bone-dry and dusting pitch at Gillingham. He said Deadly got 7 for 18 and then he added, ‘God knows how we got the 18.’ This is no exaggeration. In one such game, in wet conditions at Hastings against Sussex in 1974, Underwood took 8 for 9.

Another story goes that Geoff Boycott and Derek Underwood went out to inspect a rain affected pitch before a Kent v Yorkshire game at Canterbury. “What do you think, Deadly? 6 for 50?”. “No, Fiery”, replied Underwood, “more like 7 for 30.” He took 7 for 29.

Another amusing indication of Underwood’s worth was the occasion when he sustained a hand injury batting for England against Australia at Lord’s. Encountering Dennis Lillee in the Long Room, he was asked how the hand was, and showed Lillee his right hand, all bandaged up. “Oh damn”, said Lillee, “we were aiming for the left one.”

Derek Underwood was not only a great cricketer but a man of whom nobody ever said anything other than that he was delightful, charming, and unfailingly professional. Charming, that is, unless you happened to be facing Deadly on a damp pitch at Canterbury.