One of the world’s great puzzles is why the Americans abandoned the great game of cricket to play the inferior game of baseball. Imagine also how it might have been if cricket had spread from the US to Japan and Mexico in baseball’s stead?

Writing about the tour of the ‘Gentlemen of Philadelphia’ (the ‘Phillies’) to England in 1908 I realised that if England and the Yankees themselves had taken American cricket seriously, the US would have without doubt become a power in cricket, excelling probably South Africa and New Zealand at least and maybe even challenging England, Australia and India.

They would have had the benefit of large diasporas – English, Indian, Pakistani, West Indian, Australian, South African – and the resources to produce really good teams as they once did in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. My verdict on the Phillies was this:

“Overall in terms of first class recognized games, the Phillies won 4 and lost 6. They won most of their games overall. They performed as a lower than average but still respectable county side. Unfortunately most counties fielded inferior teams against them, probably underestimating their strength. Remember they were representing Philadelphia not the USA. Great players such as Hendren paid tribute to Bart King as one of the very best quick bowlers ever seen in England, including Barnes, Lohmann, Hirst and Spofforth. As the democratic balance shifted to baseball, the chances of the US becoming a good Test team slipped away, but imagine what might have been … With King as a potential match-winner, they might have been very dangerous in low-scoring games. The Phillies clearly had not enough batting strength, but perhaps other US teams had what was needed, I don’t know.

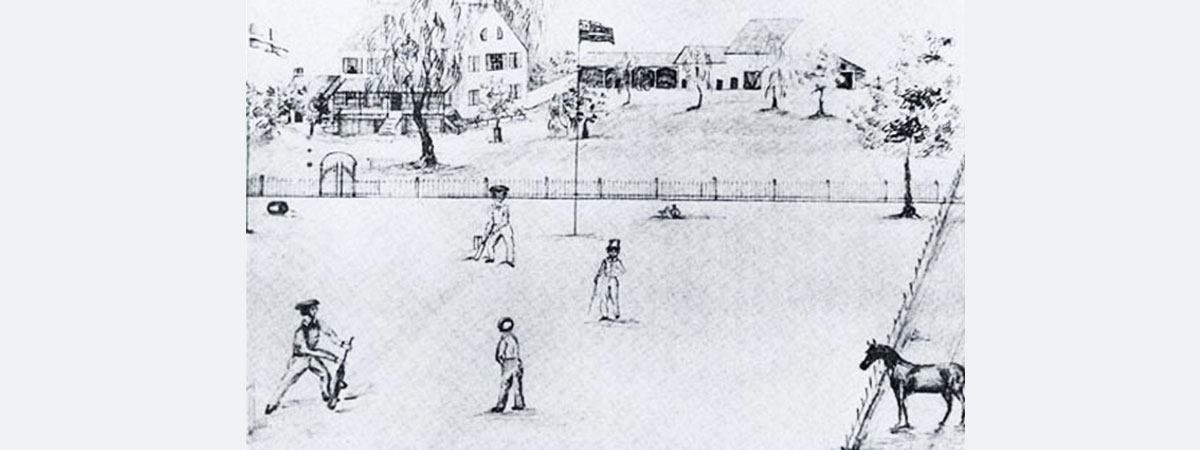

Still the US did play the first ever international match v Canada in 1844, long before England and Australia began their epochal Ashes series. The future is something else, but this side of the pond we are still hoping – see ‘Nederland’ by Joseph O’Neill.”

In England admittedly democracy was slow in arriving at Lord’s: the last Gentlemen v Players match was in the early 1960s, when amateurs and professionals still used different changing rooms and gates onto the turf. The first professional captain of England was not until after World War Two (Len Hutton).

Now, in the 21st century, roles are different. The US does have a team, mainly consisting of players of South Asian descent. Elsewhere the emerging forms of the game are more and more resembling baseball

The explanation for the lurch towards baseball is sometimes attributed to a greater regard for democratic values in the US compared to England. The cricket teams do seem to have been a place for the over-privileged sons of wealthy aristos who had time at college or later to play the longer game. But this explanation is actually questionable. After all, in England the game reached down to the lower classes, which although discriminated against in various ways were still able to fill village teams (the blacksmith usually opened the bowling), work as professionals in county and league (the latter exclusively working class), and of course to play for England, which even fielded an Indian (Ranjitsinji – mind, you he was a prince). The explanation also fails to consider why Australia (surely even more democratic than the US?) stuck to cricket as its national game and never took up baseball seriously. Perhaps the explanation is rather that cricket failed to democratise in the US in the way it did in Australia and in England itself.

Even more telling, why did cricket, the game of the hated imperialists, flourish in India of all places, followed by Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, attaining the status of a religious cult, even though it was initially the sport of the maharajahs? (To some extent I suppose it still is – at least they become maharajahs after they play well for India).

In England admittedly democracy was slow in arriving at Lord’s: the last Gentlemen v Players match was in the early 1960s, when amateurs and professionals still used different changing rooms and gates onto the turf. The first professional captain of England was not until after World War Two (Len Hutton).

The answer I think is that in the US baseball had many advantages for the working man. It took less time, did not depend on the aristocracy, and involved fewer players. People such as the Gentlemen of Philadelphia are to blame in failing to be inclusive (what if they had called themselves just ‘The Philadelphians’?).

No doubt also in the vastness and diversity of the US cricket remained a niche preserve of the Anglos living on the East coast. The English had enough trouble teaching the game to the Welsh, Scots and Irish (all now fully involved), let alone having to deal with Hispanics, Africans, Asians, and native Americans. Interestingly enough, on this theme, the first Australian team to tour England consisted entirely of aboriginals!

Faced with a puzzle it is usually explanatory to follow the money. It could be that land prices in early 20th century America were prohibitive. It needed astute entrepreneurship even in England to create Lord’s Cricket Ground in central London in 1813. But on the other hand the Americans were able to devote much land to baseball.

Perhaps the economic explanation is that the Eastern seaboard cities like New York were too cosmopolitan to sustain a game reserved mainly for upper class Anglos. Unlike London and even Sydney there was no widespread cricket culture to draw on. Baseball on the other hand was convenient and appealing to the working classes.

Now, in the 21st century, roles are different. The US does have a team, mainly consisting of players of South Asian descent. Elsewhere the emerging forms of the game are more and more resembling baseball.

Games in the Indian Premier League and its equivalents are over in three and half hours, played in coloured clothing, under lights in the evening, relayed by ‘spider’ cameras, with no draws, but with lightly-clad cheerleaders and rousing music … all we need are mits for the fielders and the transformation will be virtually complete. The Americans will have had the last laugh as the global economy of the game wins out over tradition.

Well, not quite … I notice that China played Bahrain the other day at cricket. The Chinese lost badly – but note that they have a women’s team too, as do Japan, Mexico, and Thailand. Chiang Mai even has a cricket academy run by a couple of Australians. These new teams are in the main not teams of expat Pakistanis etc., but are indigenous. Japan even has a T20 league.

The Netherlands, Denmark, and Afghanistan are familiar ICC competitors (see The Taliban Cricket Club by Timeri Murari), along with the likes of Nepal, Namibia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Papua New Guinea, and Bermuda. Indeed Afghanistan along with Ireland has now been elevated to test status. Cricket has spread beyond the world of the common law and tea at 4 o’clock (one of cricket’s charms – which other sport stops for tea at 4 o’clock?), and is now even more global than baseball.

If you believe that global economy trumps culture, then in the 22nd century we can perhaps look forward to a world-series of day-night ‘Crickball’, the final being say in San Francisco between Bangalore and Shanghai. Fortunately, as a traditionalist when it comes to the great game, I will not be around to see that.