Huish, Hubble, Ames, Levett, Evans … great work behind the wickets has been a feature of Kent cricket for long. At least two of them, Ames and Evans, served England for long and with distinction. The others were reputed to be as good.

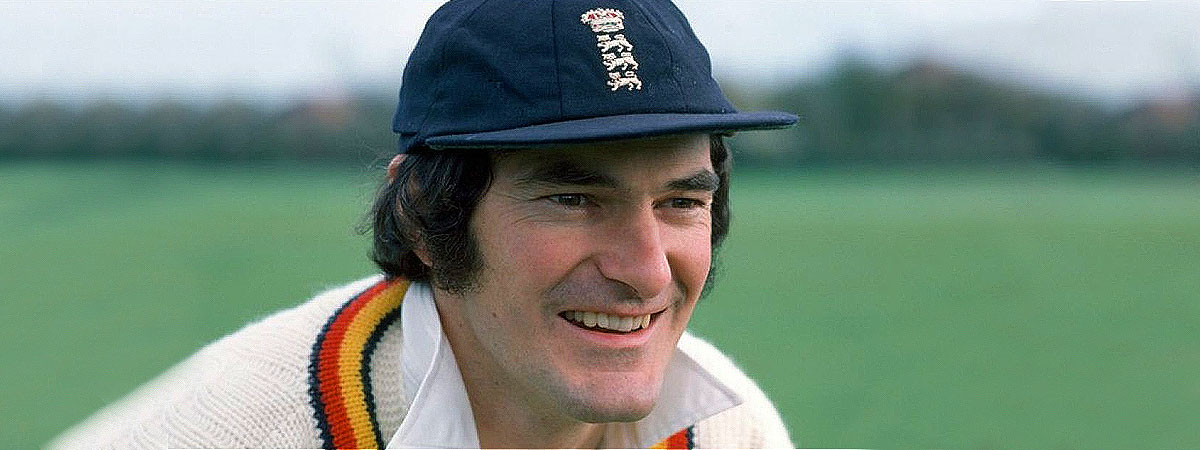

Yet, Alan Knott was special even in this league.

That could be ascertained once one saw him take balls going down the leg side with consummate ease … that too with his right hand. That was extraordinary keeping.

It is rather strange to recollect that as a very young boy, in spite of his father Eric who kept wickets for his club, Knott wanted to bowl fast. At the age of six, at the Kent indoor cricket school, he was advised to switch to spin … and rather soon developed a knack for turning the balls both ways.

Yet, in the hall of their home, father and son took turns to stand behind one another. They threw the ball against the wall. The one in front batted with a stump. The one behind held every snick off that makeshift bat. The Knott skills were thus honed.

As a 14-year-old he was already keeping with finesse. That was when Southern Counties picked him against the Midland Counties. Knott turned up in his shorts. And that was the first time he kept to another young lad who would soon be his partner-in-crime in plotting the downfall of many a batsman for Kent and England —Derek Underwood.

Also in the team, incidentally, was future England pace bowler Geoff Arnold and Manchester United footballer David Sadler.

Yet, Knott’s role was still far from being decided. Les Ames, of all people, advised him to be an all-rounder. That was before he saw Knott keep for Kent Schools and stump three batsmen one after the other. Knott actually had a problem of plenty with his cricketing talents.

By the age of 21, however, he had made his Test debut against Pakistan at Nottingham and had claimed seven victims in the match.

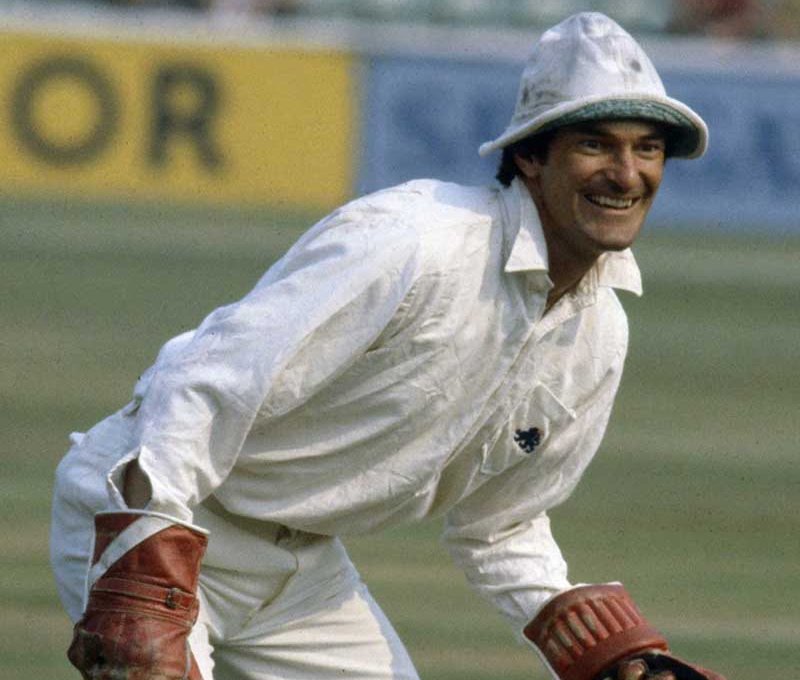

To the quicks, Knott was magnificent. The dives were effortless, aided by all the stretching exercises he indulged in every moment between balls. He got up almost always in one action, with the ball securely lodged in his gloves. And the demeanour made it clear that he enjoyed himself thoroughly. It was infectious joy.

Often he would fly through the air, bringing his gloves under the dying flight of the edge and picking it up inches from the ground, in between the first and second slips neither of whom would have managed to catch the ball. And a genuine fine leg-glance was always at risk of being pouched in those magical gloves.

Yet, he was at his best when standing up to his old friend.

Keeping to Underwood was one of the most difficult tasks in the cricket world. Knott did it beautifully. So well that England’s trump card would not hear of anyone else behind the stumps but his Kent teammate.

There were reasons for this. At The Oval, in that famous 1971 Test, Dilip Sardesai was taking control of the situation when he edged the left-armer. It was a streaky stroke that would not carry to slip, and apparently too wide for the keeper. But Knott was quick enough to reach his right hand out and hold it with a degree of ease which belied the degree of difficulty. Knott was brilliant and he knew what Underwood would bowl.

All the while, Knott’s eccentric antics would regale spectators around the world, as he contorted his flexible form into all possible, and many impossible, angles. That, according to him, helped keep him fit. And all through, his clean shaven face would be shaded by the peak of his cap, his collar would be turned up, full sleeves would cover his arms to his wrists and the gloves would take care of the rest. The attire would seem spotless in spite of all the diving around.

He would emerge to bat the same way, shaded and protected from the sun. Only, in contrast to the neatness of his outfit, his bat was often obnoxiously dirty. It frequently looked that he had indulged in some gardening before coming out to face the bowlers.

His batting was mostly reflex and eyesight, sticking to the basics of straight bat against the pacemen unless the ball was short. When the length was less than good, however, he could bring off outrageous cross batted strokes, the cut over the slips a speciality. With spinners in operation, he could sweep everything, even from outside the off-stump. Even the likes of Bedi and Chandra suffered from his plucky sweeping and gutsy use of the feet.

In fact, pluck was the watchword. When chips were down, Knott could always be counted upon, regardless of the hostility of the bowling. The more hostile they were, the better he battled.

When Lillee and Thomson made life miserable for Englishmen in 1974-75, Knott scored 364 runs with a magnificent unbeaten 106 at Adelaide. And when the West Indian quicks ran amok in England, 1976, Knott hit 116 at Leeds and managed 50 and 57 against a rampaging Holding at The Oval.

Knott finished his career, interrupted by the Packer contracts, with 4389 runs and a then world record of 269 dismissals.

The annexe stand adjacent to the pavilion at the St Lawrence Ground, Canterbury, was built in 1907. In 2011 it was renamed to the Knott and Underwood Stand.

Alan Knott would have loved the modern game, with the many outlets for his multi-faceted talents and the many opportunities for the eccentric entertainer.

Arunabha Sengupta is an Amsterdam-based cricket writer. He is the author of Apartheid: A Point to Cover — the history of South African cricket during the apartheid period leading to the cricketing isolation from 1970.