On 25th May 2020, George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis kneeling on his neck and back for over 9 minutes. Disturbing images of a black man lying on the ground screaming “I can’t breathe” as a white police officer ignored his cries beamed across the world on social media. It ushered a global movement of protests started under the umbrella term of “Black Lives Matter” (BLM).

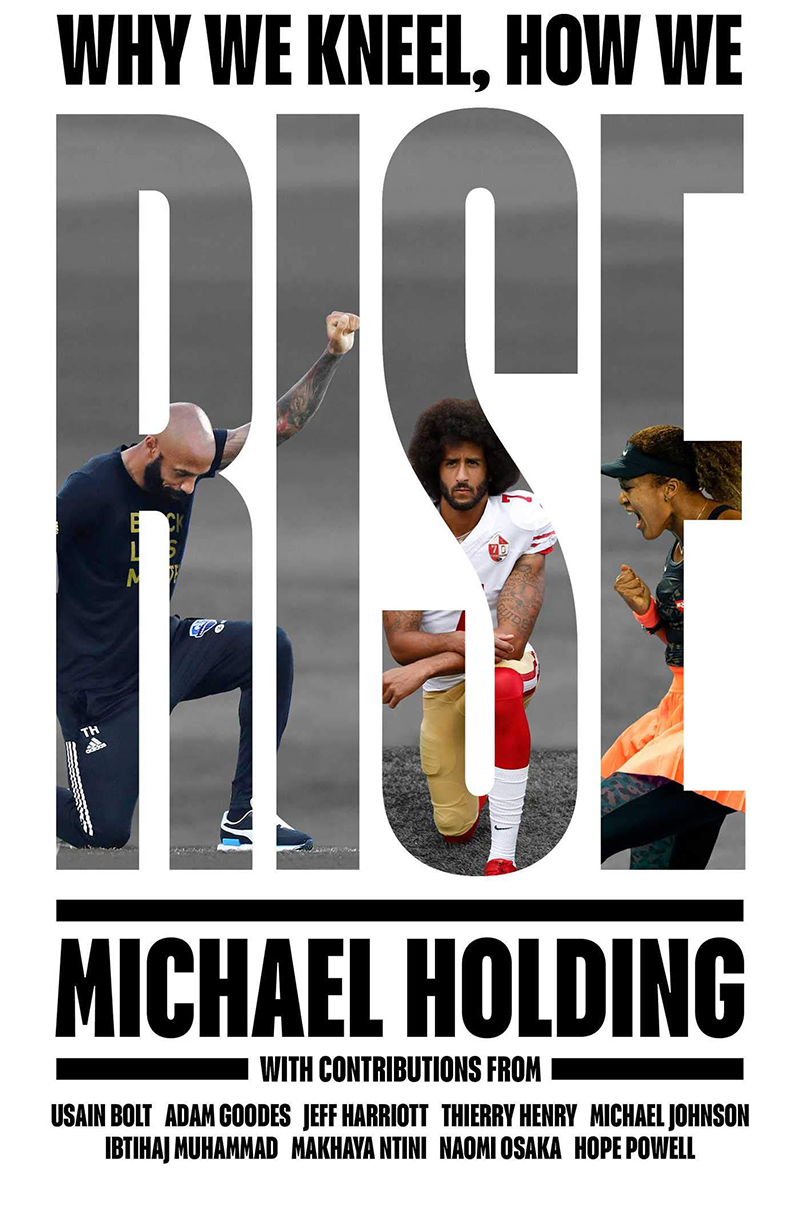

The West Indies and England teams became the first cricket teams to take a kneel during their test series in the summer of 2020 to honour the BLM movement. On a rainy morning on the start of the first test, and the day following it, in two interviews, Michael Holding unleashed a poignant and yet blistering account of his experiences with racism and how it affects society. The comments went viral and the overwhelming responses he received on them have become the basis of his new book, Why We Kneel, How We Rise.

At the onset, one must clarify that this isn’t a simple book on sport, let alone just cricket. It is a book about society and how to set right its attitudes towards people of colour. Holding has shared his story along with those of some of the most iconic and successful sports athletes from around the world, including Usain Bolt, Adam Goodes, Thierry Henry, Michael Johnson, Ibtihaj Mohammad, Makhaya Ntini, Naomi Osaka and Hope Powell.

Racism is often an uncomfortable subject, especially for cricketer administrators and players to talk about. Holding himself started the book with an acknowledgment that despite facing racial prejudice during his career playing as a fast bowler for West Indies between 1975-87 he chose to not speak about it earlier. “I was selfish” he admitted, as players that complained about racism suffered professionally. But he is choosing to speak now because he believes change can only come through confronting reality and educating people. This book isn’t simply a personal tirade of complaints, but instead a very well researched, thorough, and powerful analysis of the history of white supremacy and its lingering effects on modern society.

Holding has explained how racism dehumanizes black and other people of colour, making them feel sub-human. He traces in detail the origins of white supremacy in Renaissance thought and so-called pseudo-science about racial hierarchy. Over time these ideas created a legitimization of trans-Atlantic slave trade and other abhorrent forms of racial prejudice against Indigenous populations subjugated by European colonisers. These uncomfortable truths have been whitewashed by historians, leading to the erasure of black history. Achievements by white people have been glossed over, but those of black people have been systematically airbrushed to keep alive the myth of white supremacy.

Over centuries, much of the legal instruments of racism have been reformed, but a system of both institutional and casual racism remains. Institutional racism makes black lives harder, because they are not afforded the same chances and opportunities, so that they must work twice as hard to be successful while casual, everyday racism creates a drip, drip effect, gradually impacting people’s confidence and self-worth.

Holding argues that people aren’t born racist, it is in fact a learned behaviour. Indoctrination and brainwashing have led not only to black people being silenced but also allowed dangerous toleration for racism, so much so that an unconscious bias against black people has become the norm. Black people, Holding argues, are afraid of being discriminated against by whites, but whites are also afraid of ‘revenge’. This fear has then been weaponized to justify the indiscriminate use of violence against black people, especially by the police, ironically the very people meant to protect them.

Holding has refuted the accusation that kneeling by sports people is virtue signalling. Taking the knee is about keeping the conversation going, it is simply to remind everyone that black lives matter, because for centuries now, they have not mattered as much as others lives.

Despite the grim realities, this is not a pessimistic take on all that is wrong in the world. By narrating the stories of successful black athletes and recounting achievements of other prominent black people (an extended, chronological list is provided at the end of the book), Holding has suggested that the solution lies in reforming education. By altering existing curriculums, especially in the US & UK, to teach children what he terms ‘an unedited black history’ and having more empathic teachers, racism can be tackled head on. Any change will still be incremental, but according to Holding, must come from bottom up, educational reforms.

What does this mean for cricket? Well, for starters, it means acknowledging the reality that systemic racism, which extends through all fabrics of society, also exists in sports. Sports are after all a mirror for society. This book could not come at a more opportune time for cricket. Azam Rafeeq, the former England U-19 and Yorkshire captain had reported allegations of racial abuse at his former club last year. 1 year on, despite Yorkshire having promised an independent inquiry, nothing has been done. George Dobell at ESPN Cricinfo reported that Rafeeq had been offered a whopping £100,000 of what can only be termed hush-hush money, but he has declined. Dobell also revealed that the report carried witness statements from multiple Asian players claiming they were abused with racial slurs and coaches reporting they were discouraged from selecting Asian youngsters. The English Cricket Board has a responsibility to confront this issue, especially in light of the recent ‘historical tweets’ episode, which exposed how a number of English players had posted inappropriate racial comments on their social media accounts. The ‘education’ bit that Holding stresses on may not just be needed at school level, but for adults too, so that they can un-learn toxic and harmful attitudes that can lead to micro-aggressions and everyday casual racism.

Elsewhere in South Africa, Cricket South Africa’s Social Justice and Nation-Building hearings are underway, which have brought to light some worrying racial prejudice allegations, including the former left arm orthodox spin bowler Paul Adams alleging that current Mark Boucher and some team-mates sang a derogatory song aimed at him.

This allegation is consistent with the team culture Makhaya Ntini has described to Holding in this book where he described how he was never asked to join team meetings, how he ate alone in hotel restaurants and how he preferred to run from the team hotel to the ground to avoid the situation where his white teammates would not want to sit with him. It was shocking, and frankly infuriating to read that a player as accomplished as Ntini would feel isolated in the dressing room.

Ntini and Holding were both against SA’s quota system, which is designed to increase participation of non-whites in South African sports team by mandating a fixed number of people of colour to be in the team to accelerate racial equality in post-Apartheid SA. They argued that such positive discrimination doesn’t help and can often prove counterproductive, through a narrative where talented black athletes still are devalued because they are perceived to be there on quota, not merit and this leads to the kind of isolation that Ntini experienced.

Whilst I can understand this sentiment, and no one deserves to be treated the way Ntini was, I felt that both Ntini and Holding did not do justice to this debate which has a lot of nuances. Quota for players of colour in SA are meant as a form of affirmative action to redress the lingering impact of those apartheid era laws, to level the playing field in an environment where there exist widespread socio-economic disparities between whites and black.

Holding argues throughout his book that Black people should be treated with equality, like everyone one else, and quotas weaken that argument but doing reverse discrimination. Whilst this sounds fair, reality is often very complex. When a group of people have been systematically oppressed for a very long time, they cannot automatically and magically achieve equality the moment those oppressive structures are removed. Equality can be achieved when the playing field is level, if one group has disproportionate access to better facilities, training, resources, then how can both have ‘an equal’ chance to reach the top? If certain sports are seen as ‘white only sports’ then how can players and coaches be recruited at the grass roots levels? Yes, merit should be the sole criteria for selection for any sports team. That is the foundation of any professional sport and a good maxim to abide by in most circumstances, but SA is a unique country and apartheid has left many people of colour at a systemic disadvantage. Sometimes equity is more important than equality. All I am saying is that there are shades of grey in this debate about quotas rather than simply black and white issue, and Holding, and his ghost writer Ed Hawkins, have not fully explored those arguments within the SA context.

As Holding himself acknowledged at the end of the book, diversity norms in various organisations have brought a positive change. To erase impacts of historically legislated oppression and discrimination, you need a level of mandated inclusivity, at least for a time being, till the playing field is levelled. It is the responsibility of all stakeholders, including people of colour, to ensure that participation by marginalised groups in every aspect of society, not just sports, goes beyond ‘token participation’ of checking a diversity checkbox.

Ultimately, Why We Kneel, How We Rise is a clarion call to everybody to be allies of people of colour in the fight against racial inequality. Holding in unreserved and does not mince his words. If you do not support something as small as a sportsman kneeling to raise awareness, then it shows where you stand.

This is where Pakistanis, and generally, South Asians, can take an important lesson. Despite being people of colour ourselves, we continue to harbour unhealthy obsession with fair skin, and this contributes to a narrative where black people are seen as less desirable and even untrustworthy. Our cricketers routinely appear in advertisements of fairness creams. Sarfaraz Ahmed was Pakistani captain when he called South African player Andile Phehlukwayo “abbey kalay”. Darren Sammy was also called “kalu” by Thisara Perera in the IPL dressing room, which Sammy only discovered was a racial slur whilst watching Hasan Minhaj’s show on BLM.

Yes, I am aware the players involved have reached out to each other since, and apologies and clarifications have been made, but the number of people across India and Pakistan who rushed to provide a defence for these micro aggressions is indicative of not only of our ingrained colourism but also our acute lack of racial sensitivity. Yes, these players are black, and there’s nothing wrong in calling them black, but kalu or even kalay, is not the same as a description of the colour of someone’s skin. At best, it has a negative connotation and at worse, it is an intentional derogatory term. These kinds of racial slurs were used by white people to humiliate black people during the slavery era and can be very triggering for them. We need to be more empathetic and recognise that we have a role to play in negating the implicit bias against black people.

This is a moment in history where we can choose to educate ourselves, learn together and be allies of people of colour. I was disappointed that Pakistan team chose only to raise their hands to their chest in a symbolic acknowledgement of BLM during the recently concluded limited overs series with West Indies, even though the West Indies team had been taking the knee. Australian players who toured the West Indies before us, took the knee with West Indies players and even though England took the knee in their test series versus the West Indies last year, their team has since stopped doing that. Holding has been critical of them, and rightly so. The English football team, which recently reached the final of the European Championship, took the knee in each of their matches and has been criticised for it by a section of the English press and even some government ministers, who repeated the same troupes of virtue signalling. But the scale of the racist abuse that black English players received after England lost the final, including vandalism of the Marcus Rashford mural, shows exactly why it’s important to keep having these conversations.

And this is one of the central messages from Why We Kneel, How We Rise too, that it is better to do something than nothing, and that ‘something’ should mean having the difficult conversations. Confronting the reality and history of racism head on, the book is both shocking and inspiring at the same time and offers a message of hope about how racism can be overcome. It is richly researched, deeply impactful, emotive, and makes a passionate and compelling case for reform.