I have been delving deep into cricket’s early history in preparation for a book with Peter Oborne on the game’s first seven centuries. I should really say pre-history, because almost none of it is documented, and what documents there are do not have scorecards and match reports, although one or two carry the early equivalent of action photographs.

For England, the search carried me to 1300 and a teenager who just might have been the first royal cricketer.

This was Edward, son of Edward I. As an infant, he was proclaimed Prince of Wales by his father after he had defeated the last independent Welsh ones. He would eventually succeed him as Edward II. The king’s account books for 1299-1300 show a payment of £6 to one Lord John of Leek for helping his son to play games with his friends. The only game mentioned by name is called Creag. It is not certain that Creag was any form of cricket, but the great scholar Major Rowland Bowen said it was, and that is good enough for me. The late Major Bowen has a unique reputation among sporting historians. He deserves a history of his own. He was an eccentric who once amputated his own leg, almost as if to prove that he could, and then calmly informed the ambulance service that he had. He quarrelled and feuded with other historians and statisticians and founded a journal of his own so that he could cancel the subscriptions of those he disliked. But he was also a radical of great integrity, and an anti-racist when most of England’s cricket Establishment were colluding in apartheid.

On the authority of Major Bowen Lord John of Leek was the first cricket coach in history. If so, he was also the best paid in history. Six pounds in 1300 was a staggering engagement fee. It would have bought him 7 horses or 13 cows and represented 600 days’ wages for a skilled tradesman.

In the Victorian age, cricket became identified as a manly game for upper-class boys and perfect training for them to conquer an empire and govern it. Unfortunately cricket (or creag) did not do the same job for young Edward. On the contrary, he was regularly criticised for his love of common sports including swimming, wrestling and rowing, in the company of low-born people. He and his cricket chums would never have got into the Pavilion at Lord’s. That said, one must discount a great deal that was written about him in his time. As King he fell out with the Church. This was the main source of history and kings never got a good match report if they fell out with the Church. Worse still for Edward, he was deposed, and his queen and her lover then ruled England, in the name of their teenaged son, Edward III. Of course, deposed kings were accused of all sorts of crimes and misdeeds, including playing cricket, to justify the takeover by their successors. Edward III had a long reign and was keen to show that he was nothing like his father. In 1369 (long after he would have retired from playing cricket) he actually tried to ban it, and all others like it in an ordinance against “pila baculorea”, which is usually translated “club ball” but is generally taken to refer to a series of games in which a ball was hit by a stick.

Twenty-five years earlier, across the Channel in Flanders (present-day Belgium) an artist called Jehan de Grise illustrated a book on The Romances of Alexander the Great. In this, he produced the first image of something which looks like a organized game of cricket. It is now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. It shows a nun about to throw a ball at very close quarters to a left-handed monk swinging a bat. Her delivery looks easy to hit but there is a quartet of monks and nuns waiting for a nick in the slips.

It is striking how many women are playing this game, but they would disappear from any published narrative or illustration of cricket or any game like it for the next four hundred years.

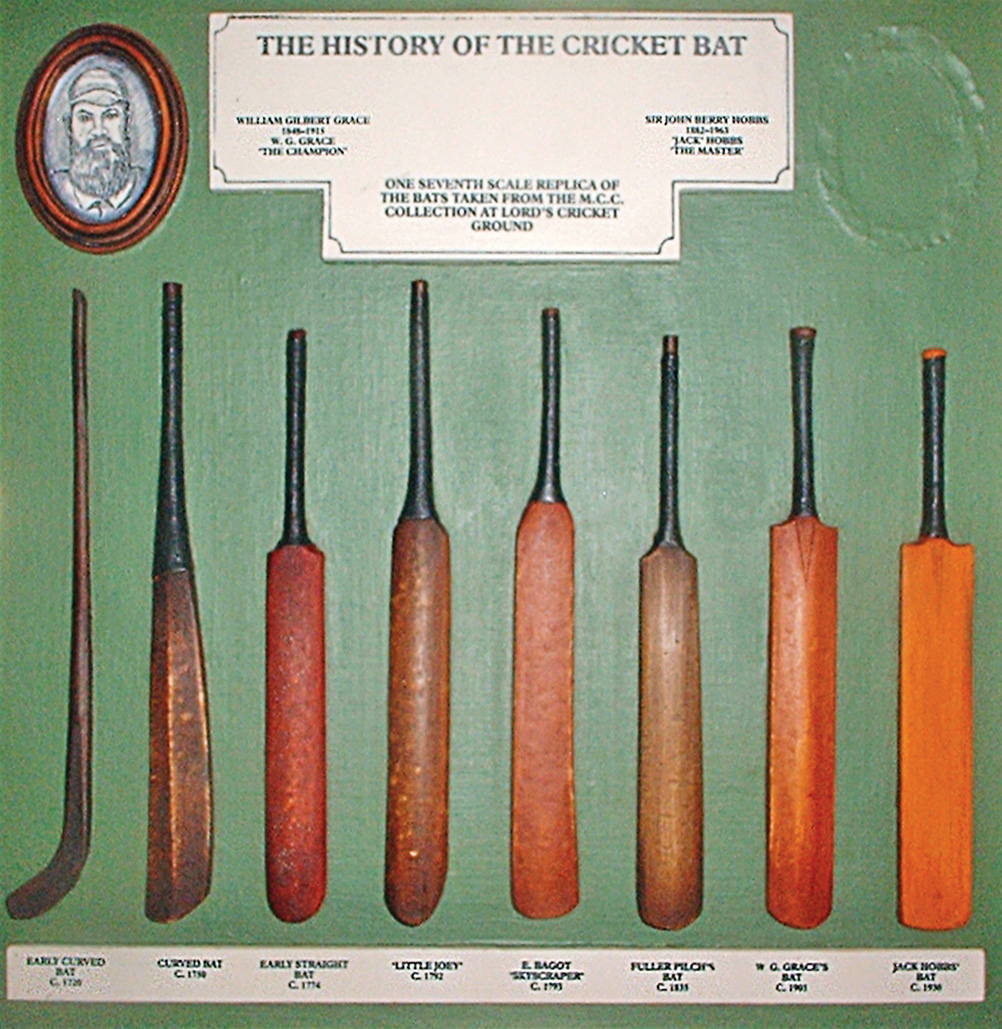

Cricket’s early history, at least in Europe, is made up of fragmentary references to games which might be something like cricket and glimpses of people playing them. There seem to be all manner of local pastimes in which someone hits a ball with a stick. Some might be the ancestors of cricket but they might also have evolved into rounders or baseball, golf, field hockey and surviving variant forms such as stoolball.

I did come across a fascinating theory that the entire family of stick-and-ball games came to Europe from the territory of present-day Iran, Pakistan and India. Their common origin is indicated in the surviving game of gilli-danda. This theory notes that neither the Greeks nor the Romans, the founders of Western civilization, played stick and ball games and suggests that Western Europe learnt them from the Romanies, and other migrants, and through a well-developed network of trade.

Pakistan has brought much innovation to cricket, notably the art of reverse swing and the creation of tapeball. It would be wonderful to think that it was part of its birth.