During the fourth Test match in India in March 2021, Rishabh Pant delivered a memorable innings that Sunil Gavaskar described as ‘the new India – a bold India’. This reminded Mark Nicholas of the iconic Sachin Tendulkar, who had astounded everyone by launching a ball straight over the sightscreen from 94 to his hundred.

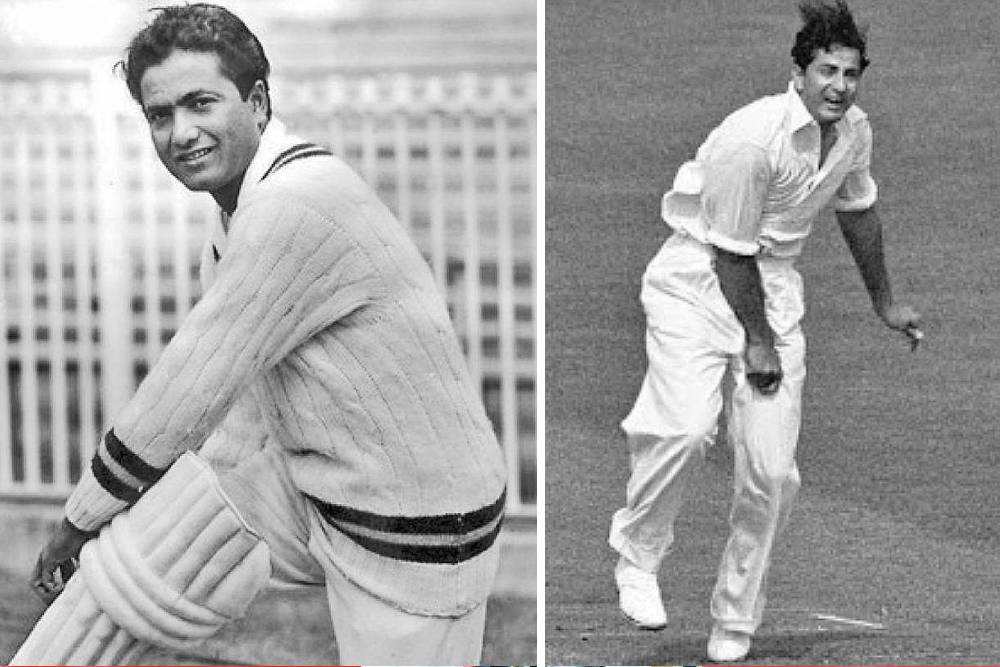

The narrator’s fascination of cricket began the previous summer, when Brian Lara visited Oxford and his mother took him to watch a match. But it was the Pakistanis that truly captivated him in 1996, with five players averaging more than 60 in the series and an impressive supporting cast of Wasim, Waqar and Mushtaq. It was as if they were playing a different game, something that a 10 year old could barely understand.

One of the defining features of modern life is the presence of technology, which has become an integral part of day-to-day activities. The ubiquity of devices and tools has changed the way people go about their everyday lives. From communication to entertainment, technology has revolutionized the way we do things.

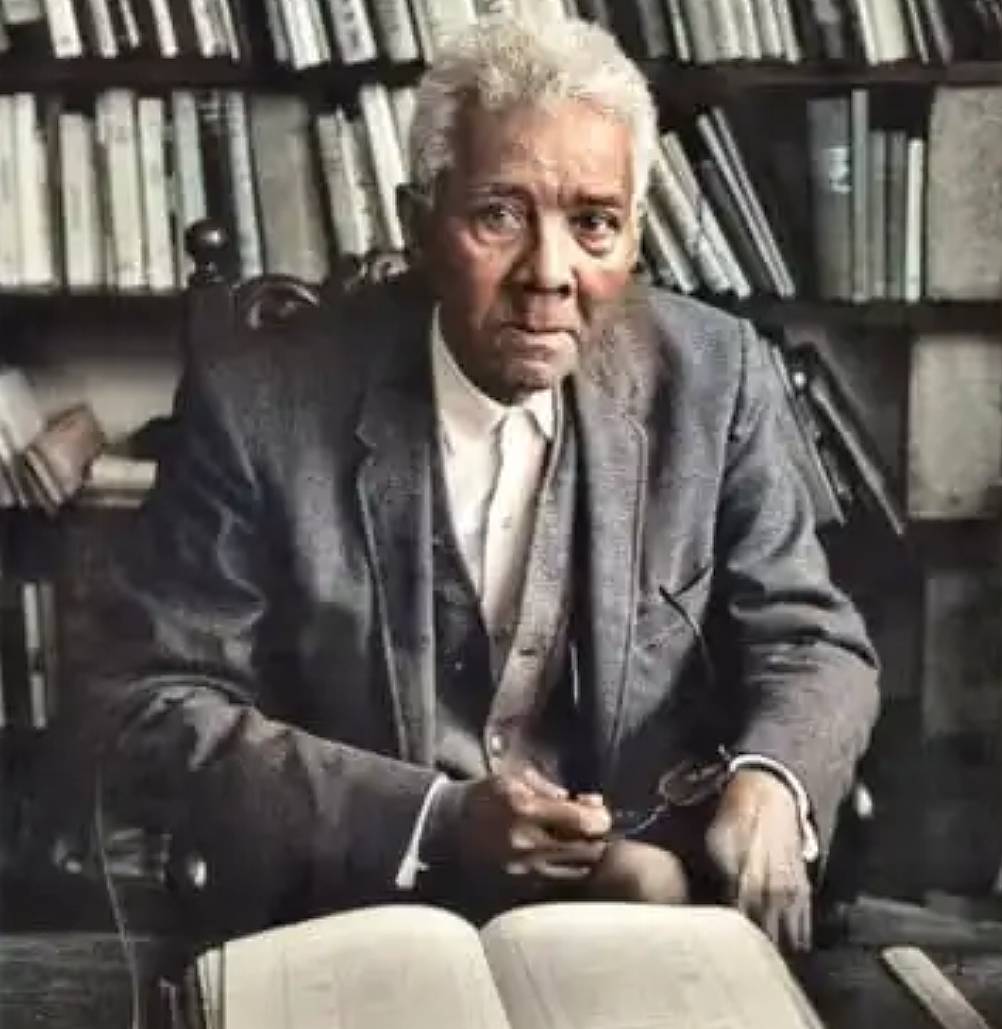

The way they played had a rawness to it, aggressive and confrontational but concealed by a languid elegance; they had the capacity to reach a higher state of being and, for those who watched, we beheld more than just a drive or a flick to leg – as CLR James expressed it, we saw how ‘a true expression of a man’s personality’ was demonstrated through cricket.

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung spoke of how, unconsciously, he sought to find his personality which had been obscured by the pressure of being European; he remarked that the logical European doesn’t understand how human nature works, even though this rationality is obtained at the cost of his vitality. This could accurately explain the distinction between Atherton and Saeed Anwar.

What I understood then was that I was witnessing a period of liminality – a moment of quiet in the tumultuous history of Pakistani cricket. I was seeing an emancipation from its shady past; the cornered tigers of 1992 had broken the limits of Pakistan’s cricketing colonial roots and unleashed it to the public.

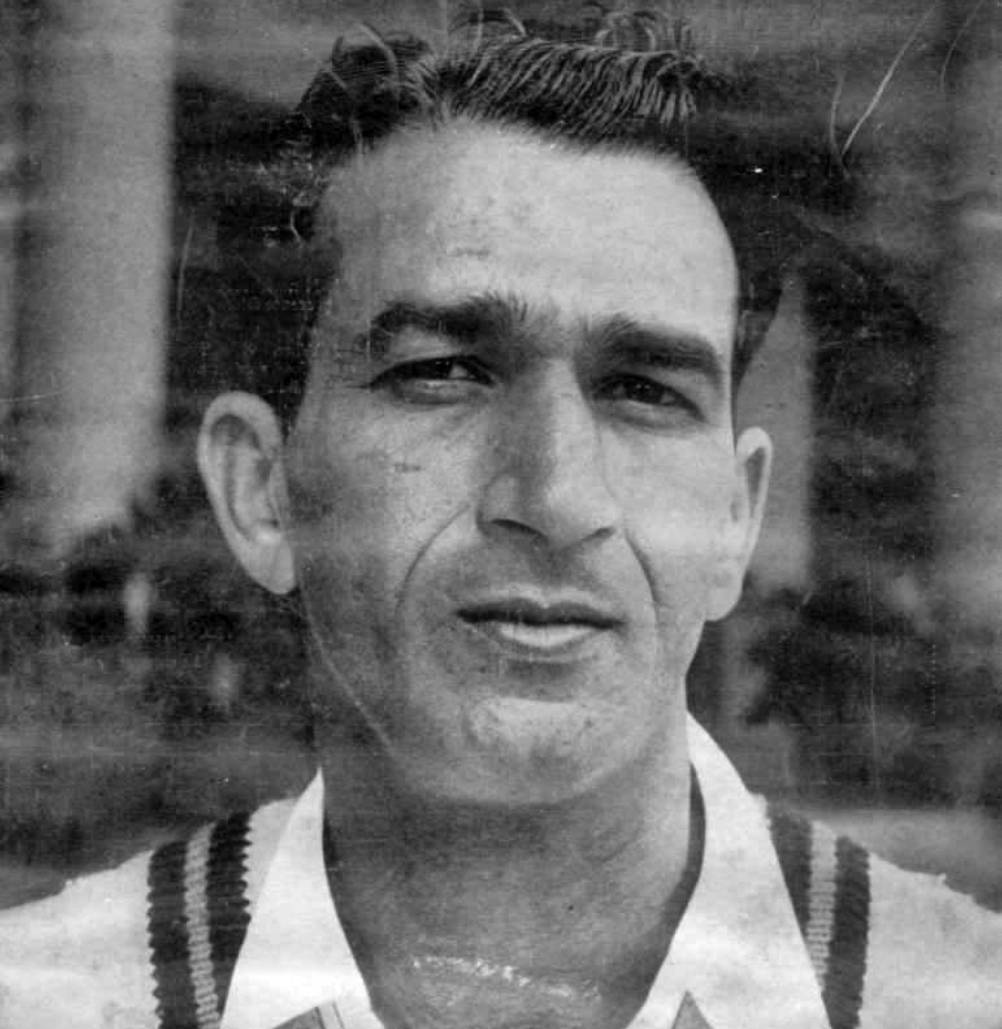

Hanif Mohammad and Fazal Mahmood were the first great Pakistani cricketers, but they still played in the English fashion defensively. While AH Kardar and Imran Khan were nationalists, they had been educated at Oxford and were thus a result of the English education system.

It is unknown how much of Khan’s career was driven by a desire to demonstrate his worth, as he was called ‘Im the Dim’ at Keble College. But AH Kardar was affronted at Donald Carr referring to him as ‘the mystic from the East’. On the same tour, the Englishmen captivated a Pakistani umpire, Idris Baig, and subjected him to what can be called as waterboarding. Carr, future secretary of the Test and County Cricket Board, later said of the incident, as an apology, ‘I think it was about the funniest thing I have ever seen in my life.’

The 1996 Pakistani team was derived from the normal people, as Naguib Mahfouz would have said, the ‘harrafish’ from the city. As James stated, ‘if style and daring can be both creative and effective it will be a demonstration of the idea that great cricketers and their style must be seen in relation to the social environment which produces them.’ Edward Said, in his book ‘Orientalism’, argued that the East was an invention of Europe. He cited Flaubert’s experience with an Egyptian courtesan, where he represented her in lieu of her expressing herself. This concept is echoed by Peter Oborne in ‘Wounded Tiger’, saying that ‘it is hard to come to grips with the set of values which led [Gatting] to take such a strong stand against allegedly poor Pakistan umpiring, yet be relaxed enough about apartheid to take a rebel squad to South Africa.’

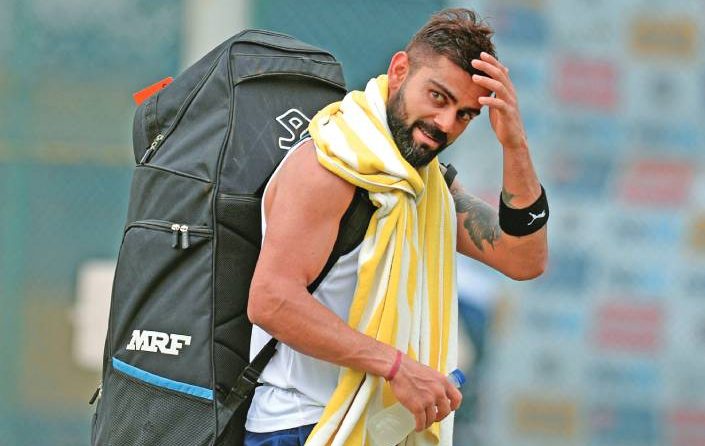

The 2002 Indian team, with Ganguly standing on the Lord’s balcony, topless and waving his shirt around, was a representation of the Indian uprising of 1857. The ‘every man’ of the English team, Freddie Flintoff, compared having Ganguly as a teammate at Lancashire to ‘like having Prince Charles in your side…’. India, with Pant and others, stepped out of the colonial shadow, possibly encouraged by Brexit, Trump, and the western world’s poor response to the pandemic. This new India seemed to disregard the public school morals that, while out of date and elitist in most other aspects of life, are still adhered to in English cricket.

Virat Kohli, with his tattoos, his beard, his brashness, and his eloquence, is the epitome of this. He sets the moral code rather than following an archaic idea of it, and is an example of ‘style must be seen in relation to the social environment which produces them.’

Ten years before Pant demolished a tired English attack, India celebrated their World Cup victory at home by parading Sachin Tendulkar around the Wankhede Stadium on their shoulders. Kohli, when he was 21, said to a billion people that Sachin has ‘carried the burden of the nation for 21 years. It is time we carried him.’ His risk of a hundred for glory, like Pietersen, is thought of as outrageous by many. But the Indian team, now, is no longer surprising. Ashish Nandy said that cricket has become a South Asian game ‘accidentally discovered by the British.’ It is time to honour that.