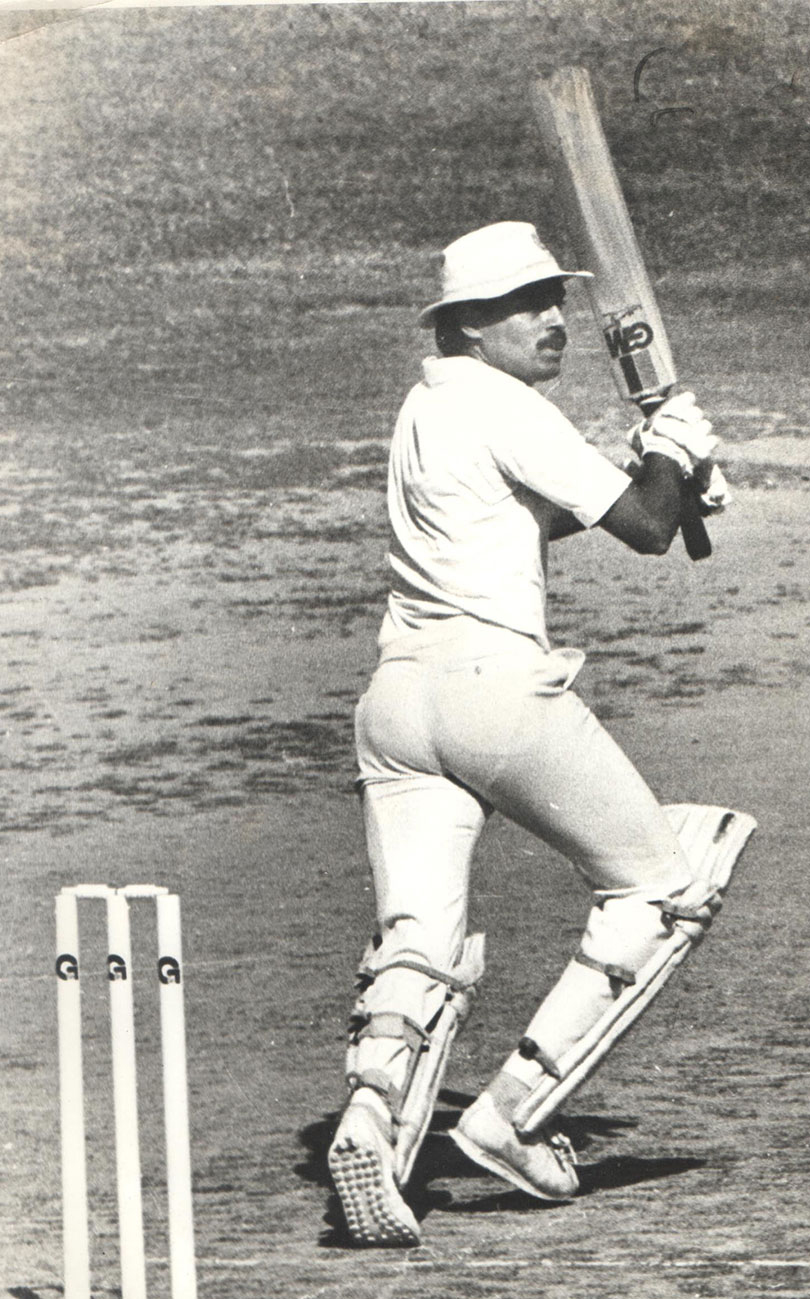

The memories are vivid. One hand held the bat, the other brushed the pads, adjusted the abdomen guard, and touched the peak of the cap or helmet. The eyes sauntered over the field, especially the on side. And then his ramrod straight figure got into his stance.

The run up of the fast bowler got underway. Our man prepared to face the delivery. He looked at his grip as he tapped the ground with his bat. And then as the bowler approached, he looked up, down again at his grip, up again, down again … as if unsure about the exact moment of delivery.

The most dedicated of his fans often worried that the ball would be delivered at the moment when he was looking down. But that did not happen. Just as the bowler was about to reach the crease the head became straight, the eyes followed his action, the bat stopped the fidgety tapping.

As the ball was delivered chances were that the front foot would be extended down the wicket, the chin would be thrust slightly forward. For a short ball the adjustment took place quickly enough. But the game was tuned for the balls pitched up. During the initial part of the innings it could look awkward. The bat coming down to meet the ball seemed nervous. It would seem that for a top order batsman he was way too shaky, way too vulnerable, telegraphing his nerves all the way across to the dressing room.

But the ones who had seen his innings in full flow would know better. As the balls were negotiated a transformation occurred. The ridiculously nervous starter became the most elegant of stroke-players. Soon his six-foot one-inch frame started leaning forward as the balls were imperiously driven, through the off-side and on and sometimes straight. The drives were unstoppable. They really were.

When he played through the cover, the legs were stretched. The head was right over the ball as if to sniff it. And the bat went through that majestic arc. The ball disappeared between the cover point and extra cover. One of the most picturesque sights of the mid-1980s.

But he was even better, most agree, when he drove between mid-on and mid-wicket. One of the most difficult strokes to play and he played them for a living. In England, during the heady season of 1986 when he got hundreds at Lord’s and Leeds, those drives were dubbed ‘rifle-shot’.

Straight drives were not that frequent, but when they were played they remained stuck in the mind’s eye. That one he hit off the young Wasim Akram at the Eden Gardens in 1986-87, the one off Pat Patterson at Mumbai the following year. Or when he was younger, more impetuous, and hit Bob Willis over his head at The Oval in 1979.

Dilip Vengsarkar had no peer while driving.

Yes, his game was heavily based on the front foot. He could rock back and cut, both fiercely, and delicately late. He could pull the short balls off both pace and spin. A short-arm pull off Malcolm Marshall at Kotla ’83 comes to mind. Yes, he was often at his best when the West Indian pacemen bowled at him. He took six centuries off them, four against the feared four-pronged attack. Michael Holding considered him the most difficult Indian batsman to bowl to.

But the one stroke he shelved was the hook. Too often it had brought about his downfall, especially on faster wickets abroad. Most heartbreakingly at Antigua in 1982-83.

Roberts, Holding, Marshall and Davis steaming in, Gavaskar and Gaekwad gone with little on the board, Mohinder Amarnath retiring hurt with injury, Yashpal Sharma not troubling the scorers much.

But Vengsarkar was batting in a different zone, counter attacking the fast men with panache, using the hook with excellent effect. Marshall was steaming in, his none too friendly relation with Vengsarkar for all to see. The more he bounced, the harder Vengsarkar struck the ball.

And then one bouncer got through, striking him smack in his helmet. Now it was war. Vengsarkar threw caution, whatever had remained, to the wind. That same over saw him pull and cut three boundaries. Into the 90s.

Marshall ran in again, Vengsarkar on 94 from 102 balls. Another bouncer, and he went for the hook. The top edge was held at long leg by Winston Davis. A valiant end to a magnificent innings. If the stroke had eluded the man on the fence and gone for six, it would have been redemption.

He scored 17 Test hundreds, 13 of them in India, 4 in England. That one hundred in the West Indies would have added the gloss that his career missed. He got 89 at Karachi against Imran and Sarfraz once again falling to a grossly mistimed hook that ended in the bowler’s hands.

He shelved his hook from 1983, bringing it back only when the drives were not getting him that many runs in the early 1990s.

He got a couple of 70s in Australia. But he did not get that hundred that would have stopped his critics from harping that he scored only in India and England.

Of course there was also an unbeaten 98 in Sri Lanka as his bat saved the match and could not shield his partners enough to get him that elusive overseas hundred.

He has to live with a record skewed in favour of home and so do his fans.

For someone who got most of his runs off the front foot, it was perhaps logical that his runs would come at home and in England.

But what a record at home!

Vengsarkar scored 3725 runs in India at 55.39 with 13 hundreds in 54 Tests.

Only Virat Kohli has more home runs than him at a better average (3766 at 62.76 at the time of writing).

Among Indians with more than 3000 home runs only Kohli and Azharuddin (3412 at 55.93) have better numbers. Yes, in India Vengsarkar (55.39) has a better average than Sehwag (54.16), Tendulkar (52.67), Laxman (51.60), Dravid (51.35), Gavaskar (50.16).

Will any All-time XI aficionado have the guts to make an Indian XI playing at home with a middle order comprising Kohli, Vengsarkar and Azhar? All teams have to play 50% of their matches at home, and All-Time XIs should not be an exception.

A detailed look at Vengsarkar’s career and one finds more such statistical curiosities. From the summer of 1986 to the end of the 1987-88 season, he had 1631 runs in 16 Tests at 101.93 with 8 hundreds. The closest in terms of average was Allan Border at a distant 63.55.

From the summer of 1983 to the end of the 1987-88 season, he scored 2772 runs at 64.46. He headed the world in terms of average (Allan Border 61.35 came second) and led the likes of Gavaskar (48.01) and Viv Richards (45.30) by several miles.

But he was born way too early for such figures to be appreciated. The Deloittes World Ranking did place him at the top of the list in 1987, but cricket statistics were not available at a few clicks during those days. The figures were hidden away in hard-to-get Wisden Almanacks in top shelves of exclusive libraries.

The legend around other cricketers were way more colourful in popular imagination than the tangible feats of this media-shy, tongue-tied, stuttering cricketer. A batsman, moreover, who even as the best of the world kept looking at his grip while the bowler ran in, looking like a novice schoolboy for the first few minutes at the crease even when averaging over 100 for two seasons.

His run-making feats brought him into the very spotlight which had a way of otherwise avoiding him. As he said, “After playing 85 Tests for India you miss a match and that ends up in a Tie.” Yes, he played 116 Tests, but the match he missed due to a strained back was the Madras Tie.

Similarly, he remained the top run-getter in ODIs for India during a considerable part of the 1980s, but Marshall (who else) hit him on the jaw during the group match in 1983 and he did not play the epochal Prudential Cup final that changed Indian cricket forever.

To be honest he did not enjoy being in focus. For the first time in his career much hue and cry was made about him when he was on the verge of his 100th Test match. Suddenly his nervousness was all too palpable. He fared disastrously in that game.

Spotlight avoided him so much that even his countrymen, when they found him at the top of world Test batting rankings, were heard muttering excuses … numbers don’t give the whole picture (and all that inane rot).

It has been said that if Vengsarkar had been born an Englishman and David Gower an Indian, the two stalwarts would have got the due that eluded them for much of their careers. Vengsarkar’s approach to the game, at the expense of everything else, was not tailored to suit Indian tastes. But he would have been the ideal English professional.

My interactions with him have resembled a typical Vengsarkar innings.

A telephonic interview was set up. He kept becoming unavailable, unexpected guests kept turning up. Later I closed in on him in London, but then he did not manage to find the time.

It was the nervous start, unpromising, sketchy.

I gave up trying to have a talk and wrote a lengthy article on his career. I sent it to him. And got the unexpected response, “Very good article.”

From time to time when I wrote about his innings we exchanged a few messages.

And then suddenly it was as if a Vengsarkar knock had matured and the drives were flowing. I texted him a question from distant Amsterdam, and he called back. We had a long and fruitful talk, the first of many. He has gone on to provide me insights that I have used for several articles and two books.

Once in his comfort zone he opened up and his conversation was as delightful after the initial stutters as a Lord’s hundred after a hesitant start.

Dilip Vengsarkar, the man and the cricketer, is like one of those fascinating novelists of yore who used to make the first chapter difficult just to make you do the hard work to delight in the rest of it.