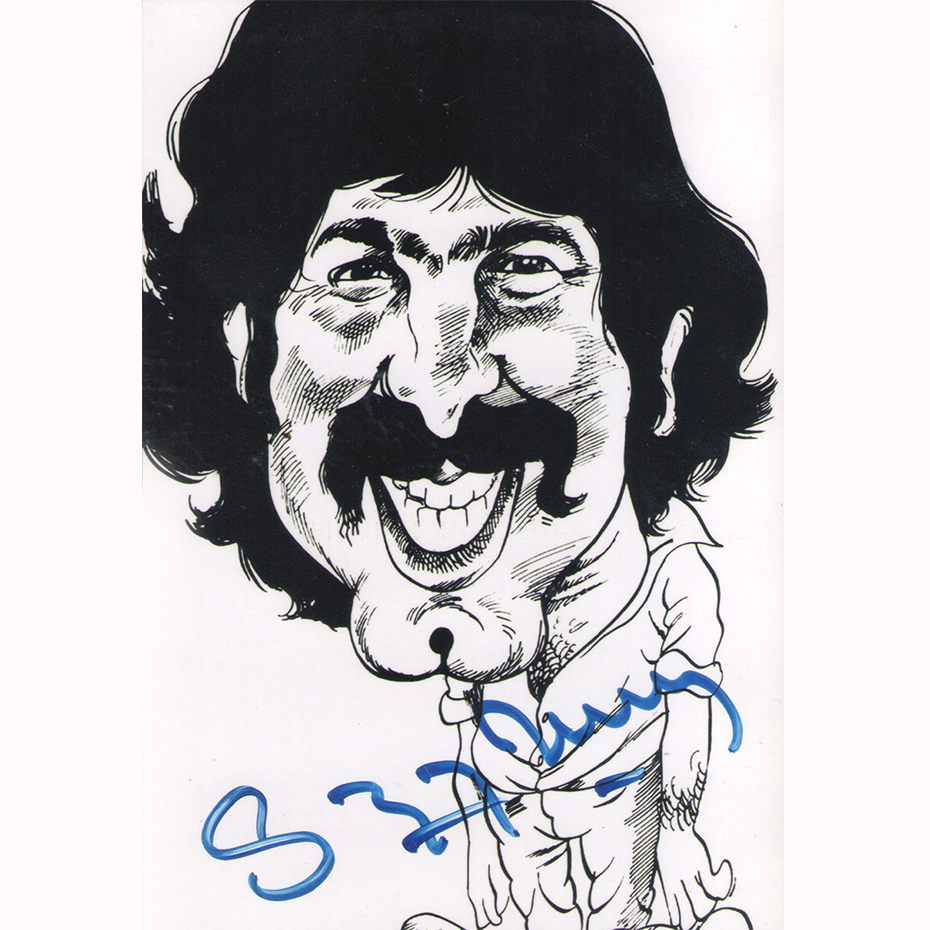

The former Pakistan swing bowler Sarfaraz Nawaz features prominently in the 1987 book Cricket Characters, by the late British sports journalist Christopher Martin-Jenkins. And for good reason. Apart from being a clever swing bowler who is credited for inventing the ‘reverse swing,’ Nawaz was also one of the most ‘colourful’ and controversial cricketers produced by Pakistan.

Now 72 years old and suffering from a debilitating bone disease, Sarfaraz still refuses to hold himself back when drawn into a discussion on the history of match-fixing in cricket, the condition of the game in Pakistan, and … Imran Khan.

Long before Khan became the prime minister of Pakistan (in 2018), he was the country’s premier bowling all-rounder. In a 1981 interview to the now defunct Pakistani monthly The Cricketer (published by Riaz Ahmad Mansuri and edited by the late Gul Hamid Bhatti), Khan referred to Sarfaraz as his ‘best friend’ and mentor.

But ever since 1992, the two men have been at loggerheads. They can’t stand each other. Khan has often called Safaraz ‘mad’ and Sarfaraz continues to explain his former ‘best friend’ and fast bowling partner as a ‘druggie’ and a ‘hypocrite.’ The last time they were seen together was during an interview on Pakistan’s state-owned PTV in 1992.

Khan had returned from Australia after triumphantly leading Pakistan to its first ever cricket world cup win in an eventful final against England. Sarfaraz had retired from all forms of the game in 1985 at the age of 36. Khan retired seven years later in 1992 at the age of 40.

Interestingly though, during the time of the PTV interview, Khan had not announced his retirement and was expected to lead the team for one last time during a long tour of England. Differences between the two became quite apparent during the interview, even though Sarfaraz was urging a reluctant Khan to lead the side in England.

However, when the discussion turned to Pakistan’s domestic cricket set-up, Khan was extremely critical of the role that government organizations (banks, airlines, etc.) played in forming teams for local first-class tournaments. According to Khan, this made domestic cricket ‘boring’ and ‘uninspiring.’

The idea to instruct state/government organizations to form teams and employ cricketers on monthly salaries, was first conceived by the ZA Bhutto regime (1971-77). Khan had largely refused to play for any of the local teams. Instead, he chose to play county cricket in England and later in Australia.

Despite the fact that Khan’s former vice-captain and contemporary Javed Miandad and Sarfaraz Nawaz were also county cricket regulars, they had disagreed with him. To them Pakistan’s first-class set-up was extremely beneficial to players coming from humble backgrounds. So no wonder Sarfaraz was dismissive of Khan’s criticism during the aforementioned interview.

But it wasn’t a sudden falling-out. In a May 29, 2020 interview that he gave to The Indian Express, Sarfaraz claimed that he had begun to resist Khan’s habit of bypassing the selectors and picking a team all by himself when he (Sarfaraz) was an advisor in the country’s sports ministry.

Nawaz had joined politics as an independent in 1985 and then, in 1988, joined the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). He was given the party ticket to run for a seat in his native city Lahore during the 1988 election. But he lost by just 400 votes. Nevertheless, he was appointed as federal advisor to the sports minister during the first Benazir Bhutto regime (1988-90).

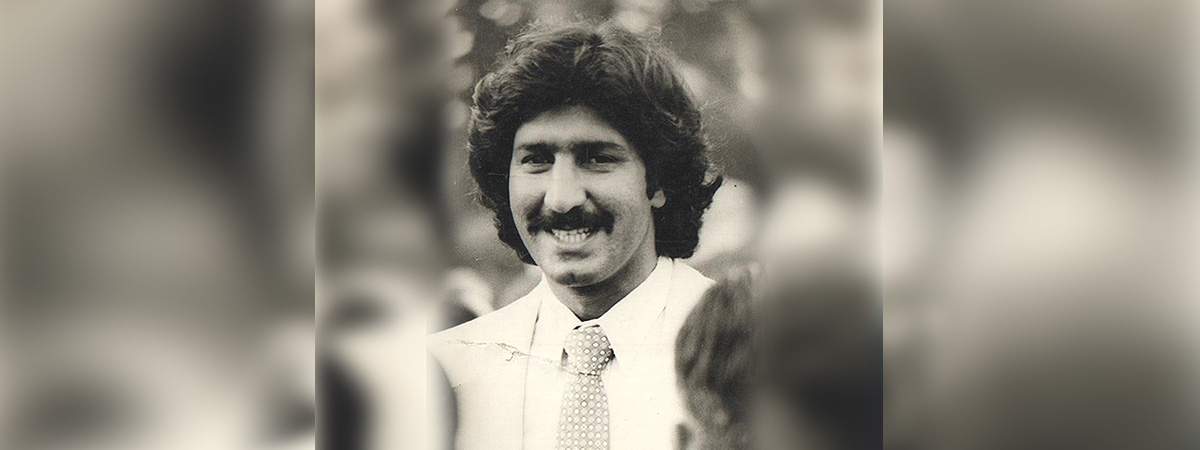

Relations between Khan and him spiraled after 1992 and their spats became increasingly public and personal. This came as a shock to those who had seen their friendship flourish. Sarfaraz came from a middle-class family in Lahore. His father was in the construction business and discouraged his son’s passion for cricket. Sarfaraz agreed to join his father’s small business but at the same time got admission into the then prestigious Government College of Lahore on a cricket scholarship. His selection in the college’s cricket team was thus automatic.

Also in the college’s side during that period were the opening batsmen Talat Ali and Shafique Ahmad and the dashing left-handed batsman the late Wasim Raja. They would all go on to become his contemporaries in the Pakistan side.

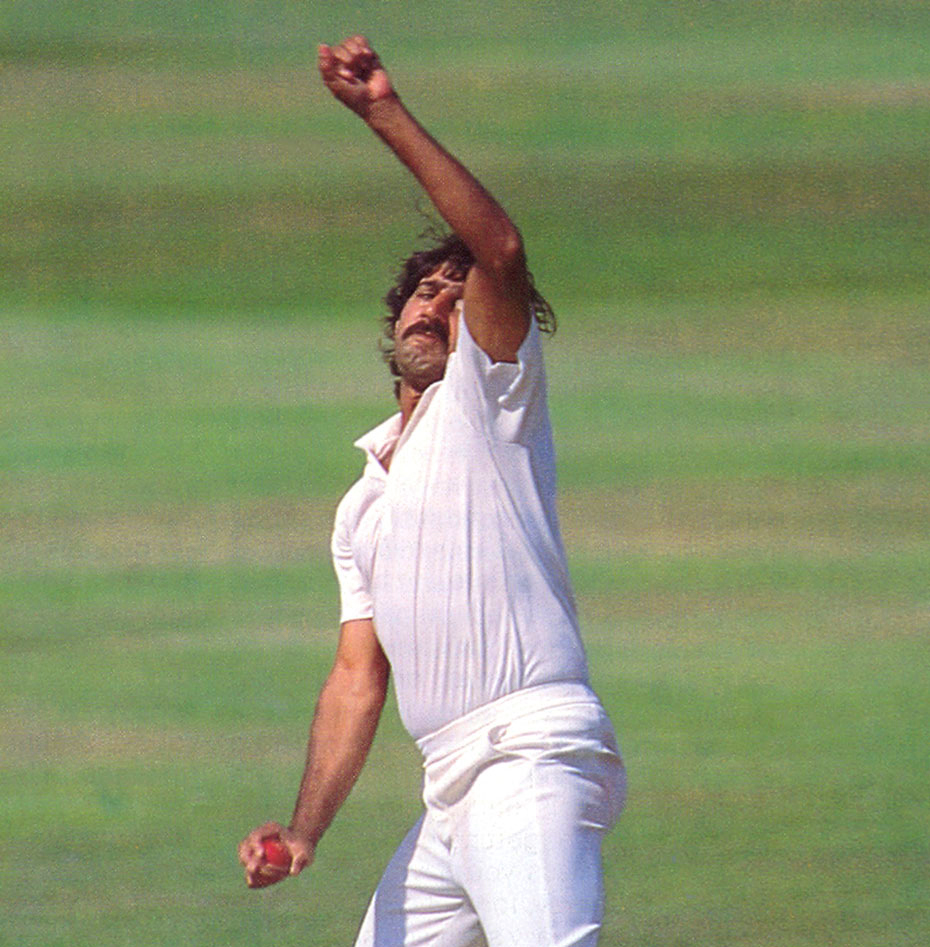

6ft 6’ and well-built, Sarfaraz initially used his body and height to generate pace. He made his first-class debut in 1967. In 1968, when a member of a visiting MCC team, Roger Prideaux, saw him bowling in the nets, he was so impressed by his pace and swing that he secured a playing contract for him from the Northampton side.

Prideaux believed Nawaz would be lethal in English conditions. But, of course, Sarfaraz was more interested in making his debut for the Pakistan side. In 1969, he got his wish. He was selected for a Test match during England’s 1968-69 tour of Pakistan. But he failed to take even a single wicket and was immediately dropped.

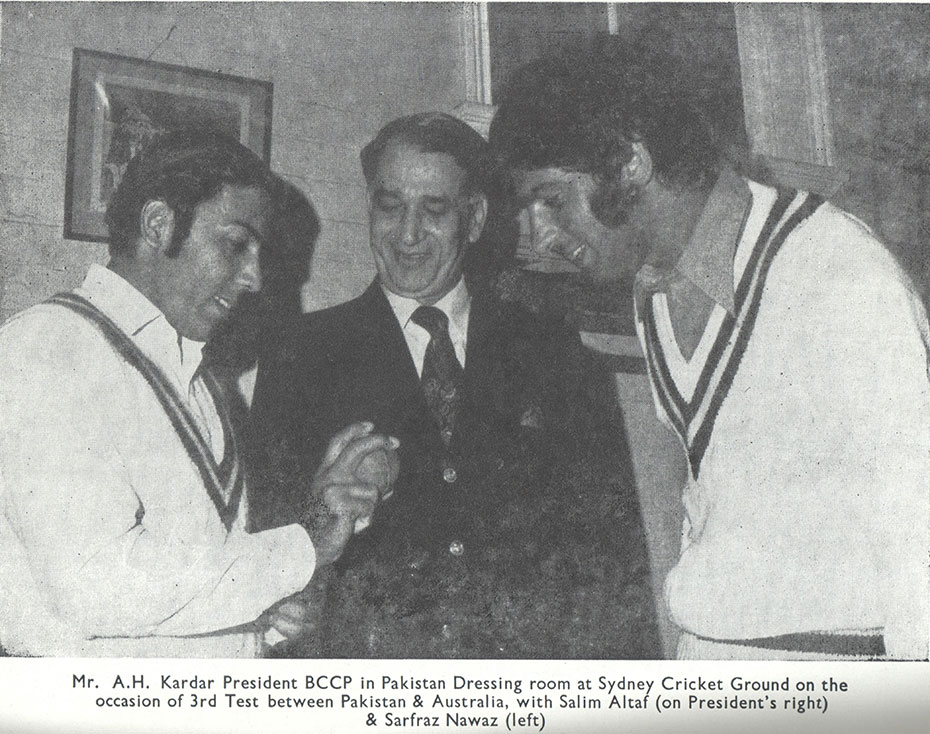

Dejected, he continued to play first-class games in Pakistan and travelled to England to play for Northampton’s Second XI. He was selected for Pakistan’s 1971 tour of England but did not play in any of the three Tests. He just got 3 side games. However, he managed to make his way back into the playing eleven during Pakistan’s tours of Australia and New Zealand in 1972-73. Pakistan’s pace attack at the time was being led by Salim Altaf and the flamboyant Asif Masood.

Sarfaraz finally began to cement his place in the side during Pakistan’s 1974 tour of England. In February 2012, he told Cricket Monthly that it was during this tour that he realized that it will be Imran Khan instead of Altaf or Masood who will become his regular fast bowling partner.

Khan had made his Test debut in 1971. He didn’t play any Tests in 1972 and 1973. But he came back stronger in 1974, impressing Sarfaraz. Sarfaraz was already in the process of developing the ‘art and science of reverse swing’ and decided that he would share it with Khan. Sarfaraz bowled brilliantly in the first ever cricket world cup (1975), even though Pakistan crashed out after losing to the West Indies by just one wicket.

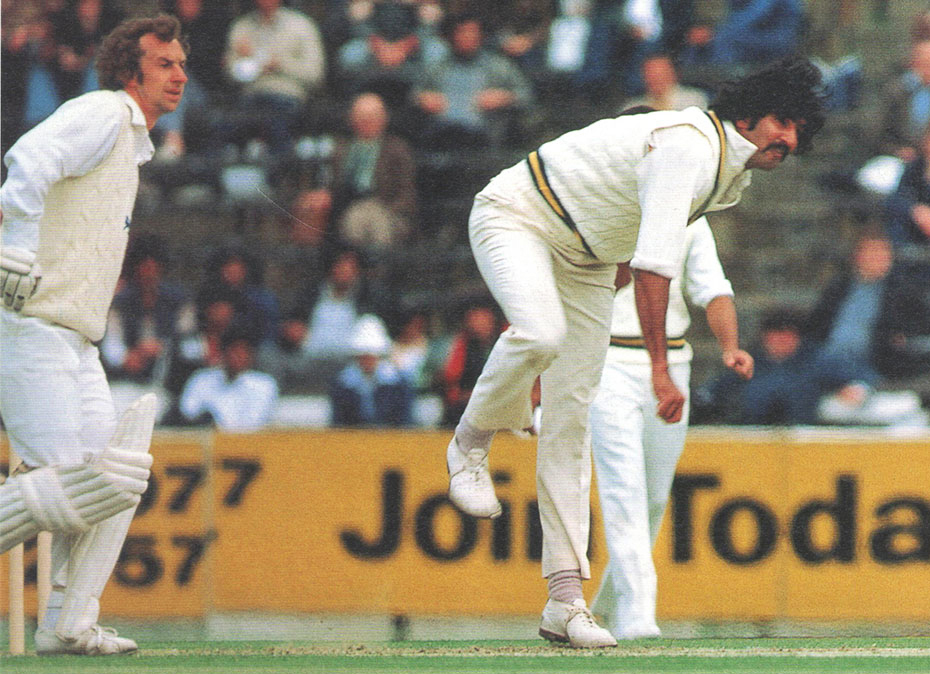

Friendship between Khan and him began to truly flourish during Pakistan’s 1976-77 tours of Australia and the West Indies. Both sides at the time were considered to be the best in the world. They were packed with fierce fast bowlers. Nawaz and Khan were instrumental in helping Pakistan win its first ever Test against Australia in Australia.

In his 2006 autobiography Inside Out, the Pakistani batting all-rounder Mushtaq Mohammad, who was captaining the side at the time, wrote that to counter the Australian side’s intimidating tactics, he chose Sarfaraz and Miandad to ‘give the Australians a taste of their own medicine’ (through sledging). According to Mushtaq, Nawaz was a natural enfant terrible. Even though he didn’t have the kind of pace that Australian pacemen such as Jeff Thomson, Dennis Lillee or Gary Gilmour had, he continued to bowl bouncers at them. During the third Test of the series, when Lillee retaliated and hit Sarfaraz on the arm with a vicious bouncer, Nawaz threw away his bat and began to curse and abuse Lillee.

Mushtaq added that Sarfaraz was notorious for tasting the nightlife of the countries Pakistan toured, often slipping out of his hotel room in the evenings and returning in the early hours of the morning. Yet, according to Mushtaq’s astonishment, Nawaz would also be the first one to board the team bus assigned to take the players to the ground. On this tour Khan began to accompany Nawaz during his escapades.

Pakistan were one-down in the series at the beginning of the third Test during the Australian leg of the tour. They squared the series against a powerful Australian side by winning the match. Sarfaraz and Imran shared 18 Australian wickets to fall in the game.

In mid-1977, five frontline Pakistani players joined the World Series Cricket (WSC) – Imran, Mushtaq, Majid Khan, Asif Iqbal and Zaheer Abbas. WSC was launched by the Australian media tycoon Kerry Packer who offered large amounts of money to international players to play in his league. The world cricket body refused to recognize the WSC. Cricket boards around the world placed a ban on cricketers who had joined WSC. All Test playing teams, except India and to a certain extent New Zealand, lost many of their top players.

Sarfaraz was also offered a contract by Packer, but he refused. Pakistan was greatly weakened by the departure of the ‘Packer 5.’ Sarfaraz welcomed their return when India toured Pakistan in 1978 after 17 years. Reunited with Imran, Sarfaraz came back into his own and both successfully rejuvenated the team’s pace attack.

During the first Test of the 1978-79 Pak-Australia series, Nawaz blew away the opposition by taking 9 wickets in the second innings. By now he had truly mastered reverse swing. The Australians just couldn’t understand how he was moving the old ball so much as they slumped from being in a winning position to eventually losing the game.

Then in mid-1979, Nawaz fell-out with the team’s vice-captain, Asif Iqbal. Iqbal was appointed captain when Mushtaq decided to sit out the 1979 world cup in England. Sarfaraz was highly critical of Iqbal’s captaincy, especially when, during the semi-final against the West Indies, Iqbal decided to drop Wasim Raja and play Haroon Rashid instead. Till that point, Raja had the best batting average by a Pakistani against the Windies.

Later that year, just before Pakistan’s long tour of India, when Mushtaq was forcibly retired and Iqbal made the captain, Sarfaraz sided with Mushtaq. Mushtaq claimed that Iqbal and Majid had conspired to oust him. Sarfaraz refused to play under Iqbal. Pakistan lost the series 2-1 and Iqbal retired.

In 1982, Nawaz joined nine other players who rebelled against the captaincy of Javed Miandad who had replaced Iqbal as captain in 1980. Sarfaraz supported the consequent elevation of Khan as captain.

After the 1982 series against England, Sarfaraz decided to hang his boots. He did not play in the home series against Australia that Pakistan won 3-0. But just before another long series against India (this time in Pakistan), Imran managed to coax Nawaz to come out of retirement. Imran bagged over 40 wickets in the 6-match series and was supported well by Nawaz. After Khan got injured and could not bowl till 1985, Sarfaraz agreed to continue playing. Once Khan returned (as a bowler), Nawaz retired. This time for good.

When Khan retired and, three years later, decided to form a political party, he found Nawaz on the opposite end. Khan, once known as a ‘playboy’ who had had steamy affairs with various famous British and Indian women, and someone who had been shown the wonders of nightlife in England and Australia by Sarfaraz, plunged into an awkward ‘born-again’ period. Not only was he seen with certain Islamic evangelists, but he also came close to the controversial former chief of the ISI General Hamid Gul. Gul had openly conspired against the first Benazir regime of which Sarfaraz was a part.

Sarfaraz launched an attack on Khan as the latter became more vocal against the ‘corruption’ of Pakistani politicians. Khan also began to increasingly air his new-found moralist rhetoric. Nawaz called Imran a hypocrite who had conveniently forgotten his own past and was now preaching morality. Khan retaliated by calling Nawaz ‘mad.’ The accusations went back and forth between the two men. In between, when the international media began to expose match-fixing scandals in the cricketing world, Nawaz claimed that the trend was kick-started by India’s Sunil Gavaskar and Pakistan’s Asif Iqbal.

After the 1999 military coup of General Pervez Musharraf, Nawaz quit politics and was briefly appointed as a bowling coach at the Pakistan Cricket Academy. But he continued to demand action against match-fixing players and mafias, so much so that in September 2010, he was approached by a group of armed men at a park in Islamabad who threatened him. They asked him to stop talking about match-fixing. In 2011, he returned to politics.

Instead of rejoining the PPP that had won the 2008 election and was in power, he joined the MQM, a Mohajir nationalist party looking to expand outside Mohajir-majority areas. Tensions between MQM and Khan’s PTI were peaking at the time. As an MQM member, Sarfaraz once again launched an attack on Khan, calling him a charlatan.

However, in 2018, when Khan became PM, allegedly with the aid and help of the military-establishment, Sarfaraz did not say anything. But once it became apparent that Khan was struggling in his new role, Nawaz changed gears again and alleged that Imran had been addicted to drugs (such as hashish and cocaine) since 1987. He said, when Khan came for dinner at Sarafraz’s house in 1987, he, along with a few other players, smoked hashish and snorted cocaine. He challenged Khan to sue him for saying this. This time, Khan remained quiet. He was too caught up trying to salvage his spiraling regime and curbing ‘fahashi’ (obscenity).

Today, Sarfaraz lives in the UK. The big, boisterous fast bowler now needs a stick to walk. But he says he has no regrets. He married thrice. This included a marriage with a famous Pakistani film actress, Rani. He was heartbroken when she passed away from cancer. Also little known is the fact that when he was in his prime, he was often offered film roles in Urdu films in the 1970s when the Pakistani film industry was booming.

But he was a rugged individualist who was only playing cricket because he loved the game. Not for the stardom and the money that it offered.

He did not join WSC, nor did he ever play in Sharjah. In 2013, I asked him why he joined politics. He replied: “I always like to speak what is on my mind. Many people do not like it. I like to remain as honest about my feelings and thoughts as possible. So I thought, maybe this attitude can benefit the world of politics.”

Unpretentious, comfortable in his own skin and outspoken. That’s what Sarfaraz was, and according to those who are still in contact with him, he still is. Sarfaraz played 55 Tests, taking 177 wickets. He also played 45 ODIs taking 63 wickets.