New Year’s Day, 1955.

The Dacca Stadium. That was what it was called.

Today it is enmeshed in the short history of Bangladesh cricket.

33 years after that New Year’s Day, in 1988, it was National Stadium, Dhaka. Under that name the venue would witness Sri Lanka beat Pakistan by 5 wickets in a low-scoring Asia Cup encounter.

By 1998, it was the Bangabandhu Stadium and Indian would be thrashing Bangladesh in the Coca Cola Silver Jubilee Independence Cup.

The next year would see the stadium host the first ever Test match in the country of Bangladesh. In March 1999, Ijaz Ahmed and Inzamam-ul-Haq would hit double hundreds. Pakistan would crush Sri Lanka by an innings and 175 runs to win the inaugural Asian Test Championship.

In 2000, a long 45 years after that New Year’s Day, on this very ground Bangladesh would play their first ever Test match.

But Test cricket in the stadium is older than Bangladesh in Test cricket. In fact, it is older than Bangladesh itself.

Curiously, it was here that the first Test in Pakistan was hosted.

And it all started on New Year’s Day, 1955—aided by nothing short of a miracle.

A stadium out of nowhere

A few weeks before the Test match, there had been no stadium. A makeshift gallery, with sporadic low-key matches—that was all there was.

Work to build a stadium started as late as October 1954. The money spent on construction amounted to Rs 3.5 million. 2000 labourers worked frantically through the month of December.

Pakistan had played their first ever Test in the winter of 1952-53. They had lost to India at Delhi, and then stormed back through some exceptional fast bowling by Fazal Mahmood at Lucknow. They had ultimately lost the series 2-1, but had done enough to make the world sit up and take notice.

In the subsequent tour of England in 1954, another wondrous Fazal spell had clinched a sensational series-levelling win at The Oval.

Now it was their turn to host a Test match. In fact, it was to be a full series of five Tests. Against India. Two countries joined together at the roots, separated by hastily drawn frontiers.

In both east and west, the border was being crossed by cricket fans.

But there were just not enough venues to host a series of such magnitude.

The country met the problem head on. The charismatic skipper, Abdul Hafeez Kardar appealed for help on Radio Pakistan … from the government, and from private citizens. The zeal was infectious.

In the east, the Chittagong Stadium was constructed in just over a year. It was at Chittagong that the Indian tourists arrived and played against East Pakistan, winning by an innings. Scheduled for three days, the match ended in two, 28th and 29th December 1954.

And all the while, in a mad frantic rush, the Dacca Stadium was being completed. The 2000 labourers worked all day, all night. Every day several new rows of seating appeared as if by magic.

There were other preparations as well, equally hectic.

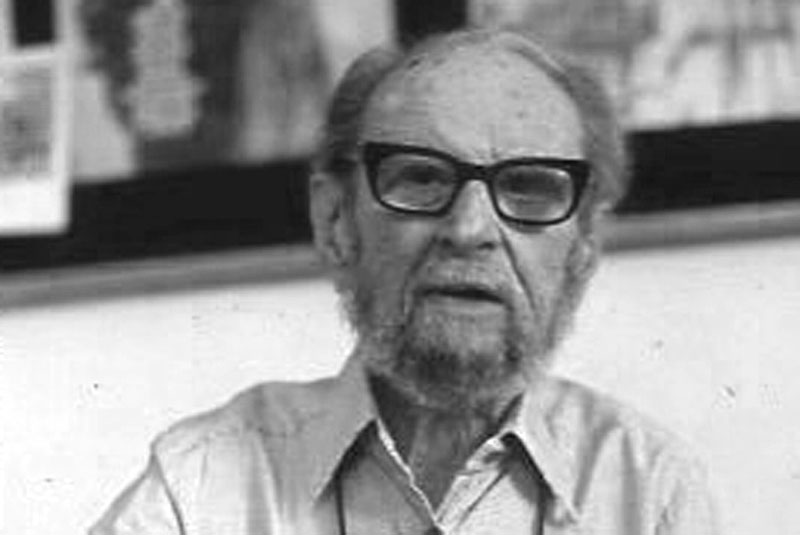

AFS ‘Bobby’ Talyarkhan, the legendary Indian journalist and commentator, was rushed in from across the border to broadcast the match on Radio Pakistan. Known variously as ‘Iron Lungs’ and ‘Marathon Man’ because of his indefatigable capacity to cover an entire day’s play without break Talyarkhan had made the Bombay Quadrangular tournaments come to life for listeners.

The Omer Kureishi would come later. At that time, Radio Pakistan had no one to do the job.

When the day of the Test match arrived, the impossible had been achieved. Well almost. The work on the stadium had not yet been completed.

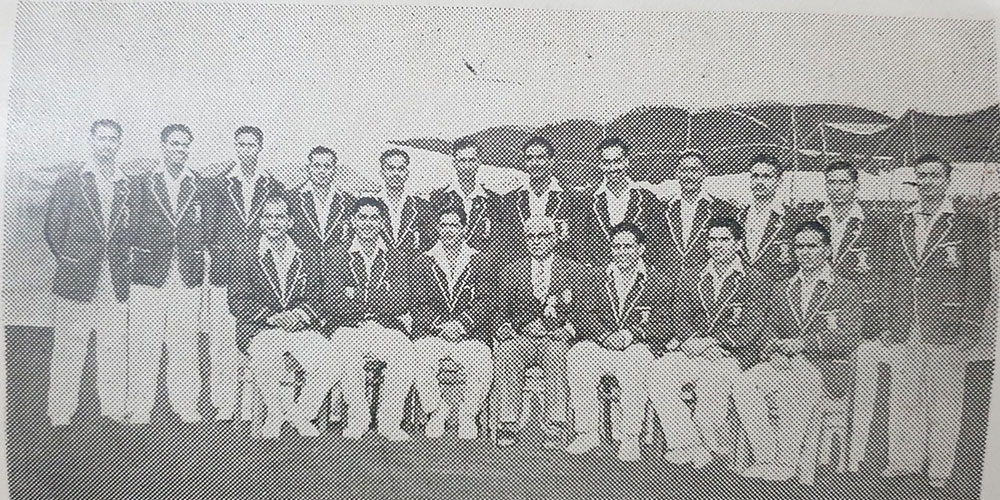

However, when Indian captain Vinoo Mankad went out to toss with Kardar, there were enough seats to accommodate 25,000 people. All those seats had been taken.

A miracle, no less.

Kardar won the flip of the coin. And when Mankad led his men out to the field, the applause was deafening.

On and off the field

There was, however, too much at stake for the cricketers.

The Cold War had not yet turned the relationship frosty. But with relationships complicated from birth and the memories of the partition all too fresh, it was more than cricket that was being contested. Neither team could afford to lose.

To paraphrase the contemporary reports in the Ambala Tribune, the onus was on saving matches and thereby killing cricket.

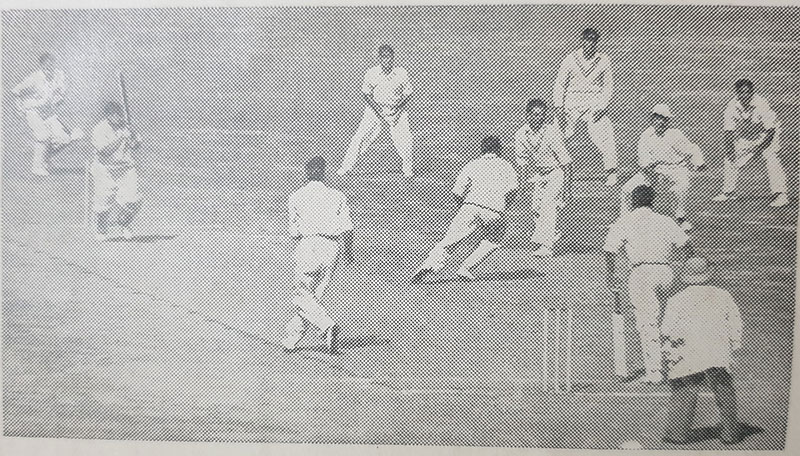

It was especially noticeable in the second Pakistan innings. On the third morning Mahmood Hussain and Khan Mohammad had dismissed the Indians for 148. Pakistan, leading by 109, enjoyed a potentially winning position. However, during the 73 overs that India bowled that day, Pakistan crawled to 97 for one, Alimuddin and Waqar Hasan stonewalling through two sessions.

That the Tests were four-day encounters did not help matters. The Dacca Test and the four that followed all ended in drab, dry draws.

However, there was no lack of drama off the field.

A reception during the inaugural Test saw sparks of tension, ignited by a fiery Kardar speech. Diplomatic gag orders prevented the press of both countries from reporting the events.

However, more than a decade and a half later, after two wars had snapped all diplomatic ties and halted cricket between the countries, Indian commentator and journalist Berry Sarbadhikary disclosed what had transpired that evening.

According to him, Kardar had recounted the triumph in England by contrasting the Pakistan performance in 1954 with the Indian capitulation against Fred Trueman in 1952. Supposedly more than the content the tone of the speech infuriated the Indians. According to Sarbadhikary, “Suddenly we saw Kardar and Mankad at a secluded corner of the vast Banquet Hall involved in an angry exchange of words and almost at the point of a scuffle.”

Sarbadhikary’s account may be a trifle sensitive and exaggerated. However Shujauddin, left-arm spinner, army officer, and a member of that Pakistan side, later admitted that there was bad blood and the two sides seldom spent time together.

Well, Indo-Pak relations, be it cricketing or otherwise, have always been quite colourful.