In the aftermath of an attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team and a grim spot-fixing uncover towards the end of the last decade various commentators called for a ban on Pakistan’s cricket. Such a notion was nothing but heart wrenching for millions – who grew up finding arguments to justify their adulation for the game.

Being a 17-year-old cricket enthusiast at the time, my state was no different! The game that ran in my blood was to be taken away. Cricket drenched me in tears thrice, as far as I can recall. I wept on the first two occasions: when Misbah scooped a dolly into Sreesanth’s hands at Johannesburg and when the pictures of the infamous string operation by a British tabloid surfaced on media. The last I shed tears (of happiness) was when I witnessed an old-fella, the reason behind my first ever cricket-related sobbing, lift the ICC Test Championship mace at Gaddafi Stadium, Lahore.

It was that moment I decided to turn the haunted old room into a depositary to keep the ground’s rich history alive,”explains Latif, who has the distinct honour of being a Marylebone Cricket Club member, for his services to Pakistan cricket

The spot-fixing controversy, the second instance, moved me the most as by now I could deconstruct the future of the team that I had adored since my first memories. In the midst of the uncertainty, during the painful summer of 2010, I found solace in the cricketer-turned-commentator Ramiz Raja’s words, “Pakistan cricket’s history is so rich that the country just cannot be kept out of the world cricket.”

Since I had been on a search for that history and came across a cricket museum in the heart of country’s cultural capital – Lahore. The discovery took me aback as I questioned myself what had kept me in dark about its existence despite being a cricket enthusiast who breathed for the first time in the very same city.

Intrigued by the fact that this is the only cricket museum in the country, I reached out to its founder and custodian Mr. Najum Latif, a proud member of Lahore Gymkhana Club. On a fine early winter morning as a weak sun shone upon the beautiful provincial capital, Mr. Latif rang to inform about his arrival at Bagh-e-Jinnah, where the isolated museum stands in the pavilion of Lahore Gymkhana Cricket Club – far away from the daily hustle and bustle of the city.

Established as a cricket facility for the British officers in 1880, the cricket ground became the only second in the subcontinent, behind Calcutta, to possess turf wickets when special clay all the way from Worcestershire was shipped for the purpose. Initially the land that served as a hot-air balloon launching site now boasts eight turf wickets.

Secured by an artistic iron fence with densetreeson the perimeter, the ground is arguably the most picturesque playing field in the country. The lush green cricket field is embellished by an old-fashioned pavilion, made from Oak Wood. “Fazal used to come here regularly and he would often stand on the edge of the ground and proclaim loudly ‘this is the most beautiful ground I have played at’ and he had played all over the world,” Latif recalls as a gentle smile decorates his face. He went on to reveal about his friendship with one of the most handsome persons to have worn their national colours in the game of cricket.

“I have been to several cricket museums around the world. I went to one in Bombay, but it only had souvenirs and history of Indian and Hindu cricketers. Here you find the history of cricket played on this ground regardless of anyone’s religious or ethnic affiliations. You find the accounts of pre-Partition cricket matches. This is a shrine of subcontinent cricket,” tells Latif as he hosted me in an elegant lounge besides the pavilion.

The museum is a private venture running without the support of the country’s cricket governing body. “It is because of my love for the game that I run this museum. I came back to Pakistan and visited the ground in 2002. Upon my request to check the dining hall, I was shocked to see it turned into a storage room. The practice nets and other equipment laid in the middle of the cobwebbed room.

“It was that moment I decided to turn the haunted old room into a depositary to keep the ground’s rich history alive, ”explains Latif, who has the distinct honour of being a Marylebone Cricket Club member, for his services to Pakistan cricket.

“We have not done anything to preserve our cricketing history and then we question why our youth is unaware about the greats,” he points out. “I have kept a patch of grass of the iconic Lord’s cricket ground presented to Mohammad Nissar’s family. Nissar played in India’s first Test at Lord’s in 1932. After his death, his family was invited to India to honour his participation in the match and his son was presented that piece of grass. Disgruntled by the lack of efforts to preserve the game’s history here, he decided to give itto some museum in India but I convinced him to hand it to me.”

Four prominent handwritten scorecards are framed on the two corners which tell the absorbing tales of the post-Partition contests hosted by the ground. The first board revisits the first-ever post-Partition first-class contest, the next first-ever unofficial “Test” on Pakistani soil

Nissar was considered to be one of the fastest bowlers of his era. His ability to nip the ball back into the right-handed batsmen at a daunting pace made him an automatic selection for the historic Test and the tall bloke did not disappoint. He bagged a five-for after becoming the first cricketer from subcontinent to get a wicket at the iconic Lord’s cricket ground.

Latif points towards the ground from the long room’s window and says: “This ground is nothing without the players. It has a rich legacy to cherish. The world’s greats from Keith Miller, Frank Worrel, Fazal Mahmood, and George Hadley to Sachin Tendulkar and Brian Lara all have played on this ground.

“During West Indies tour of Pakistan, the visitors played a side match here. People had come out in numbers to watch Lara bat, but he was dismissed early. The crowd was gutted and called for his return. After the play concluded, Lara turned out with a couple of bowlers and batted for the fans and it was lyrical. People applauded him and he showcased all of his shots,” he reminisces. But the current state of affairs takes away the enthusiasm from his tone, “That thing has vanished with cricket’s exile from the country. Our children do not see their heroes play in front of them anymore … I remember we used to stand for hours just outside this pavilion to secure a moment’s sight of our legends.”

The Lahore Gymkhana Cricket Museum and Archives is situated in a former dining hall between the home and away dressing rooms. “It used to have a large oval table on which both teams would sit together for lunches and teas.

“You would be surprised but that is what cricket used to be. It used to bring together opponents, teach them discipline. Today cricketers are treated like inmates. They travel in a prison bus-esque vehicles from hotels to grounds and are confined to their respective dressing rooms. The teams do not interact with each other and the players don’t talk to the fans,” laments the guardian of the ground’s history.

What once used to be a dining hall, it has now become home to invaluable memorabilia. Flags of seven Test-playing nations hang on either side of the windowless room. Beneath them lay memories of pre and post-Partition cricketers from subcontinent: Jahangir Khan’s All India Test blazer and cap, Abdul Hafiz Kardar’s Lord’s tie, Fazal Mahmood’s MCC tie, a cricket ball signed by Alan Border, and the first clay shipped from Worcestershire in 1882 to create the turf wickets.

There are pictures and posters of the legends – who turned up on the ground namely Keith Miller, Zaheer Khan, Intikhab Alam, Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi, Wesley Hall, R.B. Kanhai, Frank Worrel, Alimuddin, Hanif Mohammad, and Vinoo Mankad. Sunil Gavaskar, playing a backfoot cut, and Kapil Dev, in his bowling stride, hand together in a poster.

A picture of Quaid-e-Azam with Pakistan’s first Test centurion, Nazar Mohammad, hangs. Pointing towards the picture Latif says, “This is Quaid’s only picture with any cricketer.”

A few paces ahead is Virender Sehwag’s ODI cap and his famous “Britannia” bat. “During India’s side match here in 2005, I had requested Sehwag for the donation. To which he generously complied.”

On the opposite wall is Imran Khan’s picture in his bowling stride beside his signed green trouser from the 1992 World Cup campaign, which fancily the room. “I asked Imran Khan to donate something for the museum but he had auctioned all of his cricket belongings for Shaukat Khanum Hospital. I secured this trouser from one of his cousins and got it signed from him when he was bed-ridden after taking a fall before the last general elections. He was sad and disappointed due to the election results,” Latif reveals.

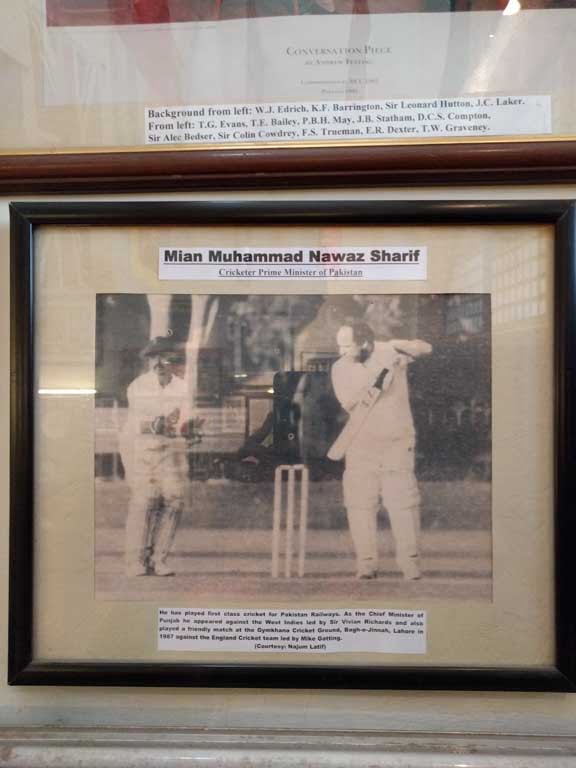

A few frames away is the picture of Imran’s present-day rival and Pakistan’s three-time Prime Minister, Mohammad Nawaz Sharif, playing a back-foot cut. Watching his feet position, one is convinced that Sharif was a mediocre batsman at best as Latif gags: “Umpires never gave him out. Leg-before was out of the question. When he [Nawaz Sharif] was caught, they used to give no balls. Imran Khan is right, the umpires never raised his finger when he was batting.”

Four prominent handwritten scorecards are framed on the two corners which tell the absorbing tales of the post-Partition contests hosted by the ground. The first board revisits the first-ever post-Partition first-class contest, the next first-ever unofficial “Test” on Pakistani soil. Facing them on the opposite wall are the scorecards of the 1955 Indo-Pak Test and the last Test match played on the ground between West Indies and Pakistan in 1959, which was Pakistan’s first defeat on home soil. “International cricket did not continue here as the Gaddafi Stadium had been constructed by this time and the board decided to take all of the cricket there.”

Since, the extraordinary playing field has been stripped of the international cricket. To rub salt on the administration’s wounds, the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) has not scheduled a single domestic fixture on the venue after 1995. “There is an impression that the club does not want to give the ground to the PCB which is totally rubbish. We feel neglected. We have been asking the board to host its matches here. When they desire, they organize tournaments. Just recently, they had organized a women’s tournament here,” he complaints.

The ground that once hosted the best cricketers from all around the world now stages amateur contests on the weekends. “They say this ground is too small for Test cricket but it hosted Test cricket throughout the 1950s. They say there is no seating space available here but during the 1955 tour of India approximately 25,000 people witnessed this ground become the 35th Test center. Throughout the matches here, the army used to erect wooden stands for the audiences here,” tells the 70-year-old Latif, who has lived through the history.

The match was a part of the first ever official Test series on the Pakistani soil. Though the Test like other four contests ended in a draw, it remains famous for Maqsood Ahmed’s 99 in the first innings. The most aggressive and carefree batsman in the initial days of Pakistan cricket, Maqsood became the first batsman from Pakistan to be dismissed on 99. Known as “Merry Max”, he turned into a sports journalist and was the first editor sports of The News, Rawalpindi. The same Test saw Miran Bux become the second oldest Test cricketer to make debut at the age of 47.

Four years later, the ground hosted its last Test match which happened to be Pakistan’s first defeat on the home soil. The mighty West Indies hammered Pakistan by an innings and 156 runs in the dead-rubber after it had lost the first two matches at Karachi and Dhaka. The match saw Mushtaq Mohammad becoming the youngest Test debutant of the time at the age of 14.

Several hurdles came in Latif’s way when he set out to secure such phenomenal accounts. But his resolve and passion for the game helped him surmount every resistance coming in his way. “Even after 14 years since I started working on the museum, no one is aware about the ground or the museum. When you inquire from the people about a major cricket venue in Lahore, they name Gaddafi Stadium. The cricket board must work to bring this facility into limelight, which has all the ingredients to resume hosting Test cricket once the cricket is back in the country. In London, there are two Test venues – Lord’s and The Oval. Why can’t we have two grounds hosting Test matches simultaneously in Lahore?”

Pakistan cricket is in much better condition today than it was seven years back. Some credit Misbah ul Haq’s quality leadership – both on and off the field – for it.It is not certain that Pakistan cricket will stay away from controversies in the future, especially considering the past record of our cricket’s ambassadors one keeps anticipating the ghastliest of the events. However, a visit to the museum affirmed my faith in Raja’s words.

Come what may, Pakistan will always be an integral pillar of the world cricket.