One thing leads to another, friendships must contain a considerable element of luck, at least in the original accident of contact. I got to know Rashid Latif in Karachi when we played university cricket, he was representing the N.E.D our matches hosted on rugged uneven grounds. We played for the Pakistan Universities he wasn’t keeping wickets, a right-handed middle order batsman, athletic and someone with peculiarly sharp reflexes.

Haider Nisar was their wicket keeper. He used to talk about his childhood friend a left-handed batsman Saeed Anwar, and he was the one helping out players with advice, fully involved and conscientious. I naturally went to him for help.

Like everyone else who knew Rashid, I had the greatest admiration for him, and was both flattered and surprised when early in 1990-91 I met him at Rawalpindi’s Hotel Al-Akbar, he was now with the United Bank Limited team. He was even then a great inspiration to and encourager of people with passion for cricket, and it was characteristic of him to order a chicken burger, even eating up the salad from your plate.

He was coming up quick and Ishaq Patel, a modest humility driven coach of the UBL could point out about him being picked to play for Pakistan. Ishaq bhai was an institution within, selfless and of high pedigree and values, his eye to catch young talent was just spectacular.

Pakistan’s first class cricket was not properly structured though the departmental teams were producing high quality players, and traditionally United Bank Limited, Habib Bank Limited, Pakistan International Airlines and to some extent National Bank of Pakistan were the major nurseries

The early 1990s were one of the most eventful periods of Pakistan cricket. Glamour of Imran Khan’s captaincy was just a nostalgic memory, his focus was changing, almost forty years of age, at the brink of an impending retirement (he had earlier been brought out of retirement in 1987-88 before the tour to West Indies by the President of Pakistan General Mohammad Zia Ul Haq) behind the present reality of their growing dominance.

Pakistan’s first class cricket was not properly structured though the departmental teams were producing high quality players, and traditionally United Bank Limited, Habib Bank Limited, Pakistan International Airlines and to some extent National Bank of Pakistan were the major nurseries, most of their cricketers pursued their way almost unaffected by international commitments.

Imran Khan having grown in success and arrogance with all his eccentricities had not really been an advocate of departmental cricket (himself becoming prominent playing for the Dawood Industries and the Pakistan International Air Lines though his cricket had dramatically improved having been with Worcestershire and Sussex in England) and having said ‘such matches have no significance, one dog and two people are present in the empty stands’, uncouth still reflective of what was true. He often talked about ‘regional nationalism’ which could only be connected to cricket through regional or inter-provincial matches.

However, he refused to play in the home series against New Zealand in 1990 citing the second string being sent to Pakistan as one of the major reasons fearing there would be no competition and also ostracizing the B.C.C.P. for agreeing playing Tests in hot and humid conditions. Javed Miandad replaced him. Little did he know international cricket would recede due to an act of terrorism and Pakistan would not be the choosers? From March 3rd, 2009 to this date, no cricket excepted, each summer has gone by without its quota of Tests and international matches. We needed to forbear here to venture a view as to what was being gained by the flight from domesticity and what lost.

Scoring 42 in 35 balls with four fours in 46 minutes taking Pakistan to an impregnable 249 in 50 overs (then a par score) and a partnership of 52 with Wasim Akram, the last memory of Inzamam of that eventful day, exceeding his own great speed of foot, improvising brilliantly and keeping his cool, he had won acclaim

Imran’s period of dominance which catapulted Pakistan’s often unpredictable team to world fame and as it could happen, some of the top youngsters were ready for international action. Wasim Akram, erroneously the credit of his selection if often given to Imran however it was Javed Miandad who had handpicked him from nowhere.

It’s true that Wasim was mentored under Imran’s aegis, there was Waqar Younis first selected by Haroon Rashid and Ishaq Patel, both saw him playing in a match at Sahiwal. He was already bowling outstandingly and with express pace playing in a Super Wills Cup match for the United Bank.

Imran saw him on television, was richly impressed and from his residence at Zaman Park he went to the Gadaffi Stadium and immediately gotten him picked on the Pakistan team to Sharjah in 1988-89. Aaqib Javed, Mushtaq Ahmed, Moin Khan, Aamir Sohail, Saeed Anwar combined with Javed Miandad and Salim Malik provided him real match winners. He patronized Mushtaq like he had chaperoned Abdul Qadir in the 1980s.

Inzamam-ul-Haq’s case was bizarre, starting as a slow left arm bowler with a suspected action he had turned to batting before starting his first class career, he had represented the Pakistan Youth in 1988 in Australia and the Pakistan U-19 versus India in 1989-90.

His timing was sublime, a natural player, strong driver, a deft cutter he had all the shots however he had become enigmatic failing in matches which were televised (coincidence) though some of the critics had tried making it a flimsy excuse for his non-selection. There wasn’t much delay making his first class debut in 1985-86 he played only one match.

In 1985-86 in five matches he scored 252 runs at 50.40, in 1988-89 posting his first double century he had ended with 387 runs at 38.70. Inzamam became prominent in 1989-90 enjoying full season, his aggregate of 1645 runs at 60.92 with six hundreds and six half-centuries attracted the selectors to him.

In 1990-91, he had virtually come of age clattering 1207 runs at 63.52 with four hundreds and seven fifties. Sent to the camp at Lahore’s Gadaffi Stadium prior to West Indies tour to Pakistan in 1991-92, there he was first seen by Imran Khan and he instantly decided to give him a chance. Javed Miandad had a sore back and Inzamam made his debut at Lahore in the 2nd One Day International, a bowlers’ back drive off Malcolm Marshall announced his arrival, though he made only twenty he had already made an impact on Imran and the rest.

In his second match, the 3rd One Day International of the series, he opened with Ramiz Raja, in the runs he scored an attractive 60 in 91 balls further convincing Imran about his unheralded talent. Earlier employed to bowl slow left arm he had picked Brian Lara’s wicket, caught by Moin Khan.

Sri Lanka toured Pakistan immediately after, and at Sargodha Pakistan won by eight wickets with Inzamam not required to bat. In the second match at Karachi he opened with Ramiz Raja and made a stylish 48 in 70 balls, a run out which was to become his trademark in a distinguished career saw him failing to disguise disgust. As captain, presumptive against Sri Lanka Imran had promoted Inzamam to open the innings, and soon he seemed to be Pakistan’s ideal man to restore their peace.

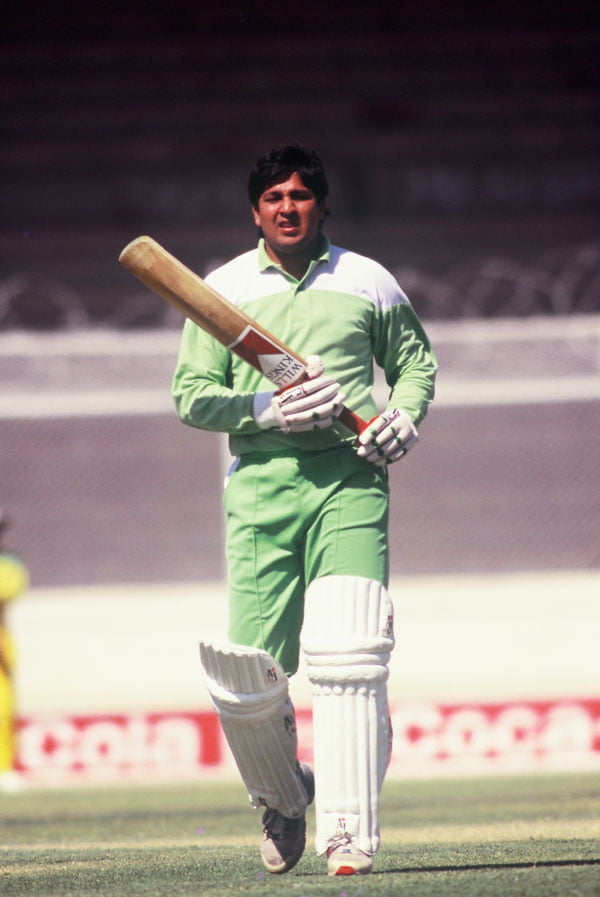

He was a dangerous hitter and a magnificent addition to the team, his performance in the series had everyone enthused, and in short he was there in full flow. Inzamam was different, and one saw him there in his finest hour, dark hair and gleaming, tall and slightly chubbier, slightly crossing his legs, holding his bat when at the bowler’s end with that air of imperturbable confidence that was peculiarly his own.

It’s true that Wasim was mentored under Imran’s aegis, there was Waqar Younis first selected by Haroon Rashid and Ishaq Patel, both saw him playing in a match at Sahiwal.

Off to Hyderabad for the third match, he looked immaculate, tireless and serene. The pitch had shed its worst, slow and low, he calmly inspected and prodded, in his zone he executed some fluent drives making 60 in 78 balls such was his awe in which the crowd was held that people wondered still whether those runs were enough. At Multan, his hometown where he had first seen Sir Vivian Richards scoring 120 in a Test in 1980 as a spectator, Inzi in full flow got to his maiden hundred, how infuriating an opponent, utterly oblivious to any hint of personal fallibility.

He wasn’t a hot hip or a stylist, but it didn’t take long for Inzamam to change the ratings; apparently sluggish he swiftly took the center stage more experienced Salim Malik even Javed Miandad was overshadowed. With Ramiz Raja he put on 149 runs for the first wicket, his own share being 101 in 121 deliveries with nine fours and three sixes. His hungry eye was on the runs, the first in circumstances which gave a revealing glimpse on his mentality as a young man. There were apprehensions Inzamam might be too vulnerable against top bowling in Australia and New Zealand what served in his home conditions would not necessarily do there.

The final flourish came at Rawalpindi, the 5th match of the series he was about as quick in detecting his chances as he was in spotting the fuller balls to be driven with ferocity and just about as ruthless in dealing with such circumstances. He walked in with a special glint in his eyes by the end of the innings, his score was 117 in 103 balls with 13 fours and a partnership of 204 with Salim Malik (102 in 108 balls, 5 fours) it was at this point at the fall of his wicket, to his great chagrin for, as he said, ‘Champaka Ramanayake was just getting his length and I was just getting my act right, it didn’t happen’.

In the Benson and Hedges World Cup in 1992 there was an interruption to Inzamam’s triumphal progress. Inzamam had been in the middle, stuttered and enthused, suffered and hoped, as his returns were 27, 14, 0, 2, 48, 16 and 11 versus the West Indies, Zimbabwe, England, India, South Africa, Australia and Sri Lanka still his position wasn’t endangered, Imran had full confidence in him.

His spirit dampened, in their last pool match versus New Zealand he hit a brilliant four and fell for 5 in 8 balls, at the airport he tried shying away from Imran expecting some bullying, to his surprise, as it could happen in the aircraft he had his seat next to him. The beggar expected the beating. Imran, one of the finest leaders still backed him up saying ‘well played’. Inzamam was perplexed, he had made only five. ‘The four you hit was from the middle’, he added. Inzamam thereafter felt relieved, he intended to live up to his early reputation.

Inzi was lucky too, Salim Malik had not been in the runs and this provided more space for him to hang onto his spot. Inzamam set the seal on a prodigious World Cup first at Eden Park in Auckland where he made 60 in 42 balls in 48 minutes with 7 fours and a six and again at Melbourne, in the final you saw all the strokes, the off-drive, cut, flick, pull and even the cow shot, the precision and the variety of his cutting specially struck one. He was delicate on the off side, elegant on the leg and adept at playing the ball off his body at all the on-side angles. He arrived with Pakistan at 197-4, Imran at number three having made 72 in 110 balls and Javed Miandad 58 in 98 deliveries, such a booster in the last overs was so essentially required.

The stranger seeing him for the first time must have noticed the exceptional quickness of his reactions, his reaction speed, and power that enabled him to take his batting in his stride. He was not as fit as one could imagine but much fitter than what we saw of him in later part of his career, not a dapper still his stroke driving from strong wrists and an exquisite sense of timing had an appeal. He didn’t lack chunkiness and was mostly at his best against high quality bowling.

When he hooked he got into position so quickly that he could hit the ball early with a downward thrust of the bat aiming in front of square-leg. Not a stylist or not an elegant batsman, not indeed in terms of such contemporaries as Salim Malik or Mohammad Yousuf, the bat had a flourish more in angles than a pendulum. But if perfect balance, coordination and certainty of execution be accepted as the principal ingredients of batsmanship, we who watched Inzamam in his early manhood will not hope or expect ever to see its art displayed in a higher form.

Scoring 42 in 35 balls with four fours in 46 minutes taking Pakistan to an impregnable 249 in 50 overs (then a par score) and a partnership of 52 with Wasim Akram, the last memory of Inzamam of that eventful day, exceeding his own great speed of foot, improvising brilliantly and keeping his cool, he had won acclaim.