Heraclitus of Ephesus, a Greek philosopher, is quoted as saying “change is the only constant” in life. Cricket ever since its inception as a competitive sport has traditionally been averse to change. For long periods of time it jealously guarded its novelty as a sport for the English speaking elite or their colonial subjects. Something unlike the soccer playing or following crowd of commons rather a sublime activity reserved for gentlemen. Rarely a sport has been so much immersed in traditions and one which prides itself for its values, exclusivity, records and idiosyncrasies. It remained the same till the dawn of the seventies decade in the last century.

The cricket world of the 1960s was not greatly dissimilar to its inaugural face of ninety odd years ago when the first Test match was played at Melbourne in 1877. The “Swinging Sixties” which started with the cricket’s first ever tied test was a actually a lull before the seventies storm. History of international cricket is spread over 140 years but no ten year period has seen the whole sale change implemented so swiftly and across the board as in the 1970s. The transformation of cricket from the pastime of gentlemen to a modern day professional sport was a revolution second to none. The journey from classes to masses was rapid and made significant impact in the lives of players as well.

For a fleeting moment revisit the cricket world of 1969. The world of Test matches played in white flannels and commentated upon by doyens of cricket voices like John Arlott of England or Alan McGilvray of Australia or our own Omer Kureishi. The days when appeals were mere polite enquiries and bowling 120 overs a day was considered a norm. Fielding was a poor third distant cousin to the arts of batting and bowling. Then came the seventies, and the changes started hitting cricket right left and center.

It all started with the advent of one day limited overs international cricket. The abandonment of the Melbourne Test match resulted in the first ever one dayer being arranged between England and Australia in January 1971. Within four and a half years of that unplanned 40 overs a side match, the first limited overs World Cup tournament was staged in England. Before the seventies decade was out the cricketing world had seen two World Cups both sponsored by Prudential Insurance and both lifted by Clive Lloyd at Lord’s and ODI cricket had carved its niche in the conservative cricket world. Viv Richards whose electric fielding broke the back of Australia’s chase in the 1975 final by effecting multiple run outs , hit a gorgeous century four years later in the second final against England to put up a daunting total well beyond England’s capabilities considering the firepower of the West Indian pace attack.

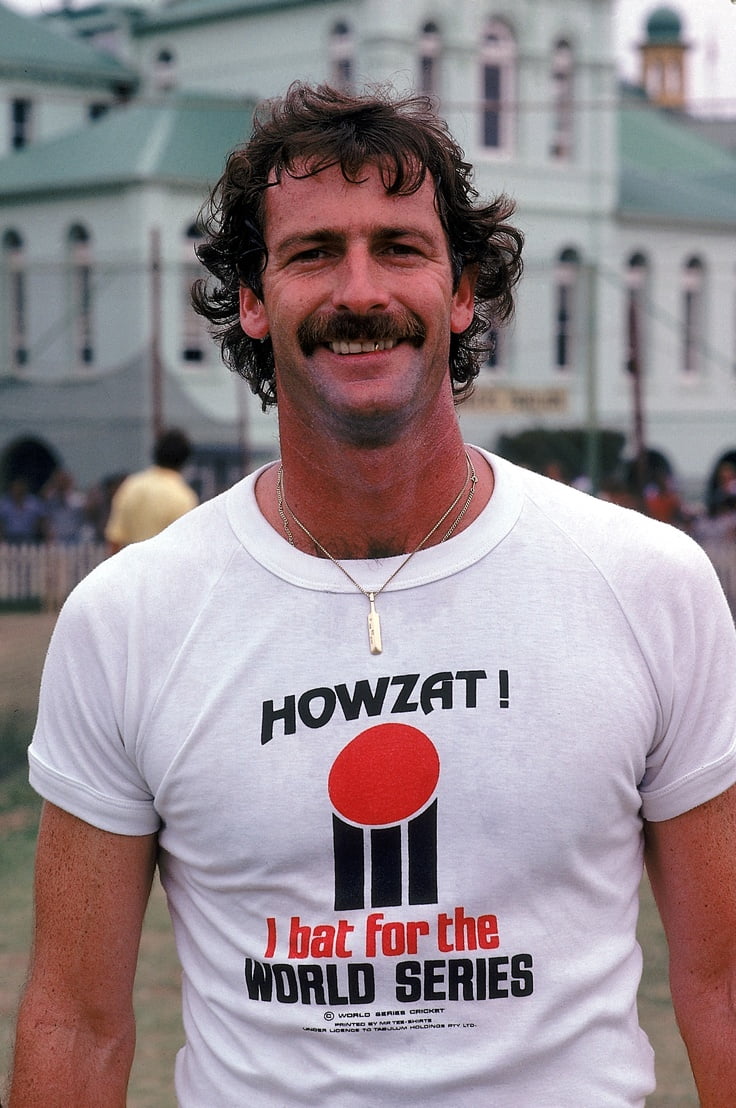

In between the two World Cups the Kerry Packer “revolution” stung the cricket world and brought in many new concepts which are now considered as a part and parcel of the game. A fight over television coverage rights between the Australian Cricket Board and the Channel Nine initiated launch of parallel cricket universe by the Australian media tycoon Kerry Packer. Apart from luring the best of the cricket talent from across the globe with previously unimagined lucrative salaries. Packer introduced innonative concepts like day-night cricket, colored clothing, white ball and exquisite television coverage with former players like Bill Lawry and Richie Benaud as commentators. All these innovations were looked down upon by the traditionalists. Packer brand of cricket was initially labeled as a circus and pyjama cricket by the ruling conservative cricket boards across the cricketing world and players were branded as mercenaries and ousted from respective national outfits. However, it took less than two years for sanity to prevail and changes to be accepted and players integrated back into the main stream cricket.

Tony Greig, the English captain became a champion for cricketers’ rights and was instrumental in setting up the entire Kerry Packer circus as his technical advisor and chief recruiter. He was ably supported by the Australian out spoken skipper Ian Chappell and Pakistan’s Asif Iqbal both known for raising their voices for players’ rights previously. Greig, was also the biggest advocate of the protective head gear which was also introduced in the same period. Greigy shocked the entire cricket fraternity by appearing nude in a print advertisement for St Peters (SP) brand wearing only cricket gear over his tall frame. Sunil Gavaskar invented his own protective cap and Graham Yallop batted in a test match using motor bike helmet. Viv Richards however always batted in his West Indian cap and never ever used anything else.

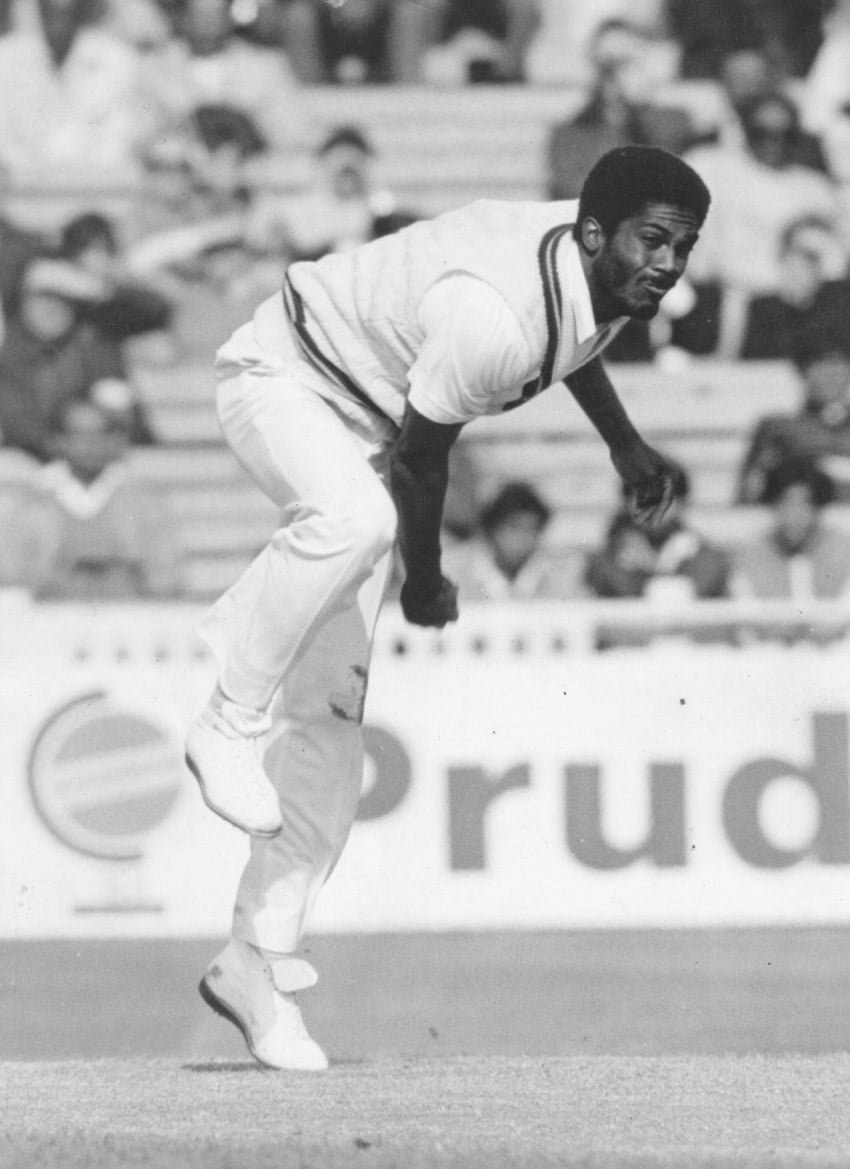

The main reason for haste in introduction of the high quality protective gear was the West Indian team which started unearthing a never ending supply of fast bowlers all of whom looked menacing, clocked above 90 mph and bowled mean lengths directed at psyching the batsman out and hurting him so badly that mere survival became name of the game against their ferocity. Scoring runs was a luxury not everyone afforded against their four pronged pace attack. Andy Roberts was the first one from this fearsome production line quickly followed first by the duo of Michael Holding and Wayne Daniel and then by Colin Croft and Big Bird Joel Garner.

Their defections to Packer saw discovery of even more fearsome duo of Sylvester Clarke and Malcolm Marshall. Just to think of the fact that bowlers like Franklyn Stephenson and Ezra Moseley never even were able to break into the sixteen or seventeen strong touring squad, speaks volumes about the wealth of pace bowling riches at the disposal of Clive Lloyd and his successors. This attack coupled with batting might of Greenidge, Haynes, Richards, Kallicharran and Lloyd created arguably the strongest team ever to grace a cricket field.

While the West Indian pace battery was busy in terrorizing batsmen of opposing team with their constant diet of short and fast stuff, our own Sarfraz Nawaz introduced a technique which changed the dynamics of pace bowling in the years to come and is now considered a lethal weapon for any pace bowler’s armory. Yes I am talking about reverse swing which was first restricted to Pakistani pace bowlers like Sarfraz, Imran and his disciples Wasim and Waqar. Who can forget Sarfraz’s magical spell of taking seven wickets for one run at Melbourne when Australia were 300 plus for three chasing a 380 runs target. Rest of the world looked at reverse swing suspiciously and few even considered it as cheating. These murmurs of illegality lasted only till Pakistanis shared their trade secret around the pace bowling fraternity around the world and England’s Darren Gough became the first non-Pakistani pacer to master this art. From there onwards it became a fast bowling skill.

Standards of fielding rose exponentially along with the levels of sledging and appealing on the field. While Tony Greig introduced the suicidal hand shaking fielding positions like silly mid on and silly mid off on the 1972-73 tour of the sub-continent. Dennis Lillee, the great Aussie fast bowler, pioneered the art of intimidating umpires by appeals which are more like threats rather an enquiry for dismissals. Ian Chappell the aggressive Australian captain gave new dimension to the on field chatter and the art of sledging was born and it was refined further by our own Javed Miandad and subsequent generations of Aussie cricketers.

So if a cricket buff actually had the opportunity to time travel from 1969-70 to 1979-80 he would have actually been more surprised at the changes in his favorite sport rather than the fact that he has fast forwarded ten years in a jiffy. From white ball to red ball, from five days to one day, from cap to helmet, from sunlight to floodlight, from white uniform to colorful ones, from conventional swing to reverse swing and from gentlemen to sledgers, it all started in the 70s and remained there since.